Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533. National Gallery London.

With Halloween just around the corner, many are eager to experience the seasonal chills and thrills. Look no further than the art museum, which is full of frightening depictions from biblical horrors, to Greek mythology, and pure existential dread. Here are ten great artworks to put you in the Halloween spirit.

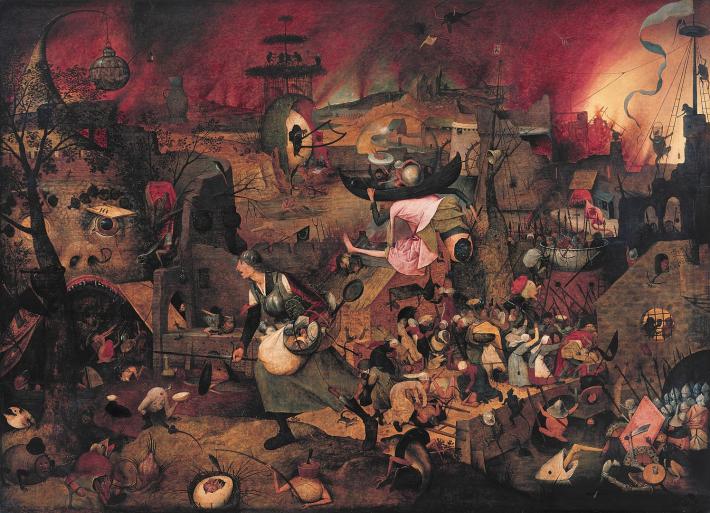

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Dulle Griet (Mad Meg), 1563. Oil on panel. Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder's depiction of a Flemish folktale gives us a vision of the gates of hell. Griet, which was shorthand for an uppity or nagging, loud woman, is shown leading an army of angry women to pillage hell. Their greed and brashness is no match for the demons they encounter, as they wear armor and wield weapons in order to collect their treasures.

Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring His Son, c. 1819–1823. Oil mural transferred to canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Goya's famous image of the titan Saturn gobbling up one of his children is dark, gruesome, and terrifying. After a prophecy foretold that one of his sons would usurp his throne, Saturn devoured each of his children, viscerally depicted here. As disturbing as the image is, can you imagine eating breakfast looking at it? Goya painted this directly on his dining room wall at his home outside of Madrid, one of his fourteen Black Paintings that adorned his walls and has since been transferred to canvas.

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Oil on canvas. Detroit Institute of Arts.

This famous painting truly captures the experience of a nightmare—the paralyzed helpness, the menacing demon, and the haunting, bizarre, mare. Fuseli's The Nightmare was a hit as soon as he exhibited it in 1782 at Royal Academy of London. The overt eroticism coupled with the palpable terror of the scene continues to captivate us.

Albrecht Dürer, Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513. Engraving.

One of Dürer's three Meisterstiche (master prints), Knight, Death and the Devil showcases the artist's incredible skill in both engraving and symbolism. A brave knight and his dog fearlessly ride by the frightening embodiment of death as a rotting corpse, taunting him with an hourglass, while a goat-headed devil lurks behind him.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors (Double Portrait of Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve), 1533. Oil and tempera on oak. National Gallery, London.

Like many well-crafted horror movies, terror lurks beneath the surface of an otherwise placid scene in Hans Holbein the Younger's The Ambassadors. The two men seem to have it all: depicted in fine clothing against a lush backdrop with an array of worldly goods, they confidently confront the viewer. But all is not as it seems, as scholars believe that many items in the still life symbolize conflict, and when the viewer approaches the canvas from a different angle, the strange shape at their feet reveals itself to be a large skull, the looming specter of death.

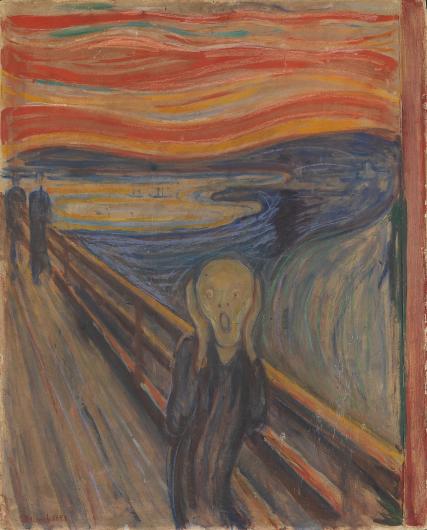

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Oil, tempera, pastel and crayon on cardboard.

Munch's Scream is art history's most famous and prevalent vision of terror. The artist masterfully captures a universal feeling of anxiety and powerlessness. Munch's own fear of death and mental illness strongly influenced his work. From the mask in the Scream movies to the screaming emoji in your smartphone, the influence of Munch's iconic masterpiece is hard to overstate.

William Blake, The Ghost of a Flea, c. 1819–20. Tempera mixture panel with gold on mahogany. The Tate, London.

Anyone who has battled with fleas in their home will have no trouble relating to William Blake's miniature painting showing the devilish creature in all its glory. In contrast to its minuscule stature, Blake shows the menacing insect as hulking and muscular, poised to drink from a bowl a blood.

Peter Paul Rubens, Medusa, c.1618. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Even in death, Rubens' Medusa is terrifying. The Flemish master's depiction of the famous Gorgon's severed head is gruesome and powerful, her withering gaze is undiminished while the snakes in her hair continue to writhe in protest. In the Greek myth, Perseus, who slayed Medusa, gifts her head to Athena, who places it in her shield and uses Medusa's deadly gaze as protection.

John Martin, The Great Day of His Wrath, c. 1853. Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

The English Romantic painter John Martin did not shy away from drama, as demonstrated by this epic biblical scene showing the destruction of Babylon. Instead of visiting hell, as we see in Dulle Griet, hell is brought to us, and it's not pretty. Martin may have been inspired by the industrialization of the English countryside, which littered the formerly peaceful, lush landscape, with billowing smokestacks.

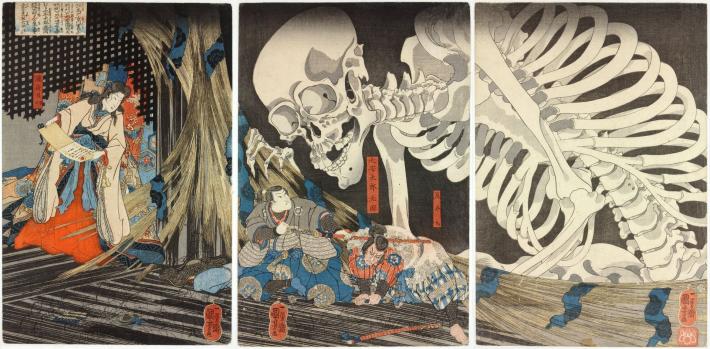

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter, c. 1844. Wood-block print.

As a master of wood-block printing, Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicts here one of the legends surrounding the real-life tenth-century princess Takiyasha. Shown reading a spell from a handscroll, the powerful witch-princess summons a massive skeleton to frighten away an enemy. The skeleton menaces the tiny figures with his bony hand while the princess looks on.

Chandra Noyes

Chandra Noyes is the former Managing Editor for Art & Object.