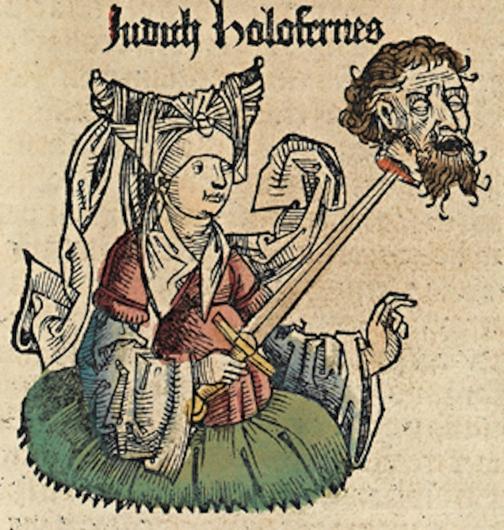

Judith beheading Holofernes is one of the most popular art historical subjects of all time. The biblical story began to appear in artwork during the Renaissance and continues to be reinterpreted to this day—most often as a means for modern artists to put their work in conversation with art history at large.

Judith, a young widow of Bethulia, took action to save her people who were under siege. She went to the enemy camp dressed in her best clothes and sought out the general Holofernes, who had openly desired her. She convinced him that she had and was willing to share information that would lead to his success but that she had to wait for a sign from God. While waiting for said sign, she plied him with food and drink. Once he was asleep, she took his sword and cut off his head.

While the story itself has never changed, the manner in which it is executed certainly has. Though many renderings of Judith depict her as a multi-dimensional person, others do lean on rather thin tropes of womanhood. From icon of virtue to seductive temptress, the range of referenced stereotypes is remarkably wide.