One of the mummies within a sarcophagus recently excavated from the newly discovered cemetery at Tuna al-Gebel in central Egypt.

2023 was a busy year in the world of archaeology. With numerous exciting and important discoveries made around the globe, this was a year that continued to prove just how much we still have yet to learn about our collective histories. As such, many of these new discoveries have either expanded our knowledge of the ancient world and its peoples or provided us with astonishingly beautiful or well-preserved examples of ancient craftsmanship, ingenuity, and artistic talent. From newly discovered Etruscan tombs in Italy to entire Maya cities in Mexico, 2023 did not disappoint. Though we’d love to tell you about all of these amazing discoveries, we’ve elected to pick a selection of what we think are five of the most exciting archaeological finds made this year.

Over the summer, researchers from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) discovered the remains of a Maya city that had been hidden beneath the dense jungle cover of the Balamkú ecological reserve for over a thousand years. Thought to have once been a critical regional center in the area during the Maya Classical period (250-1000 CE), the city was built atop a peninsula of over 123 acres and played host to many large structures including several pyramids reaching almost 50 feet high. The site also contained numerous stone columns—Ocomtún in the Mayan language Yucatec Mayan (which is spoken in the Yucatán Peninsula)—after which the site was named. The team from INAH also located ceramics, city plazas, and a ball game court. According to the research team, the decline of the city of Ocomtún appears to align more broadly with the collapse of Maya civilization in this area between 800 and 1000 CE, allowing us to add another piece to the historical puzzle of the Maya people and their lives.

Image: Ruins of Ocomtún building and staircase.

Although a well-known site, the archaeological park of Vulci in the Montalto di Castro municipality of central Italy presented yet another treasure to archaeologists this year. A never before seen Etruscan tomb was opened late this Fall after having slumbered untouched for over 2,600 years. The rock-cut tomb, which was initially discovered earlier in the year, was found to be remarkably well preserved and structurally intact containing a trove of pottery, amphorae (ceramic storage vessels for wine and oil), utensils, cups, iron and bronze objects, and decorative accessories including even the remnants of a tablecloth. Based on the quality of the finds, researchers believe the family interred here would have been relatively wealthy, possibly holding a position of importance within the Etruscan community at Vulci. These finds will help researchers to not only further color in the local history of Vulci but also continue expanding what we know of the Etruscan peoples more broadly.

Image: Pottery and Metal vessels located inside the previously untouched 2,600-year-old Etruscan tomb at the archaeological site of Vulci in central Italy.

Early this past spring, researchers located two 500-year old shipwrecks 1,500 meters below sea level, in the South China Sea. One of the wrecks, according to Chinese archaeologists, dates back to the Ming Dynasty’s Hongzhi period (1488-1505) while the second wreck dates to slightly later during the Zhengde period (1506-1521). Both vessels were carrying an impressive amount of goods including over 100,000 pieces of fine Ming-era porcelain as well as stacked timber, specifically persimmon lumber. The ships appeared to have been heading in opposite directions with their respective cargo and were located within 12 miles of each other on the seabed floor. Considering the proximity of these two vessels in both time and space, researchers are thrilled by what these ships can tell us about maritime Silk Road trading routes and reciprocal flows of goods during this era.

Image: Thousands of Ming-era porcelain vessels now lay at the bottom of the South China Sea as a part of a 500-year-old shipwreck on a Silk Road maritime trading route.

Located at Tuna al-Gebel in central Egypt, archaeologists announced the discovery of a New Kingdom-era (1550-1070 BCE) cemetery. Though excavations have been ongoing at the site since 2017, the cemetery was newly uncovered just this year. Appearing to be relatively untouched, the cemetery contained a rich collection of mummies, sarcophagi, amulets and shabti figurines (figures meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife). Even more tantalizing, however, was the discovery of a 43-49 foot papyrus scroll of the Book of the Dead. The Book, a name given by modern scholars, actually refers to a collection of varying, customized texts that were buried with deceased individuals as manuals of sorts to help them navigate the underworld. Thus, no two Books of the Dead were alike, there being no standard or canon version, making this discovery an exciting addition to our knowledge of New Kingdom burial practices.

Image: One of the mummies within a sarcophagus recently excavated from the newly discovered cemetery at Tuna al-Gebel in central Egypt. Credit: Egyptian Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities.

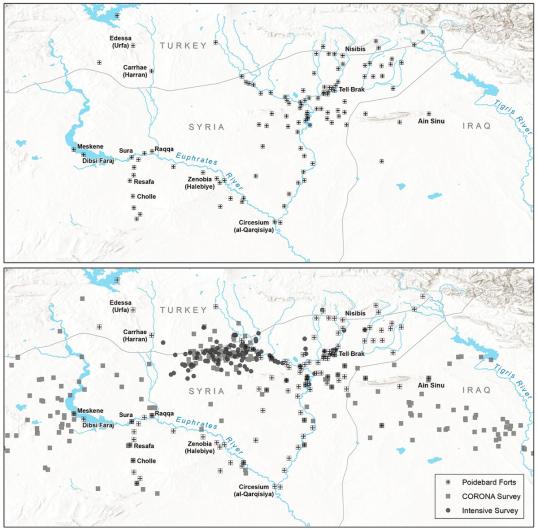

Building off of work begun in the 1920s, archaeologists at Dartmouth College utilized declassified spy satellite imagery to locate a grand total of 396 previously undocumented Roman forts spread across modern day Syria, Iraq, and Jordan. While about 116 forts had been previously noted in this area as serving purely defensive purposes on the eastern border of the Roman Empire, the new research, which located the additional 396 forts, suggests that actually this “defensive” line was part of a vast east to west caravan-based interregional network that facilitated the movement of goods, peoples, and ideas. This is a critical expansion of our knowledge in this area since many forts and sites on the eastern borders of the Roman Empire remain unexplored. What is more, these conclusions also help strengthen newer theories that challenge Roman “borders” as being static and strictly defined lines and instead support the view that they represented dynamic areas of cultural exchange.

Image: Maps created by archaeologists (J. Casana, D. D. Goodman, and C. Ferwerda) showing the previously known 116 forts (top) compared to the expanded map with the additional 396 forts (bottom). Credit: J. Casana, D. D. Goodman, and C. Ferwerda, Dartmouth College, Department of Anthropology.

Danielle Vander Horst

Dani is a freelance artist, writer, and archaeologist. Her research specialty focuses on religion in the Roman Northwest, but she has formal training more broadly in Roman art, architecture, materiality, and history. Her other interests lie in archaeological theory and public education/reception of the ancient world. She holds multiple degrees in Classical Archaeology from the University of Rochester, Cornell University, and Duke University.