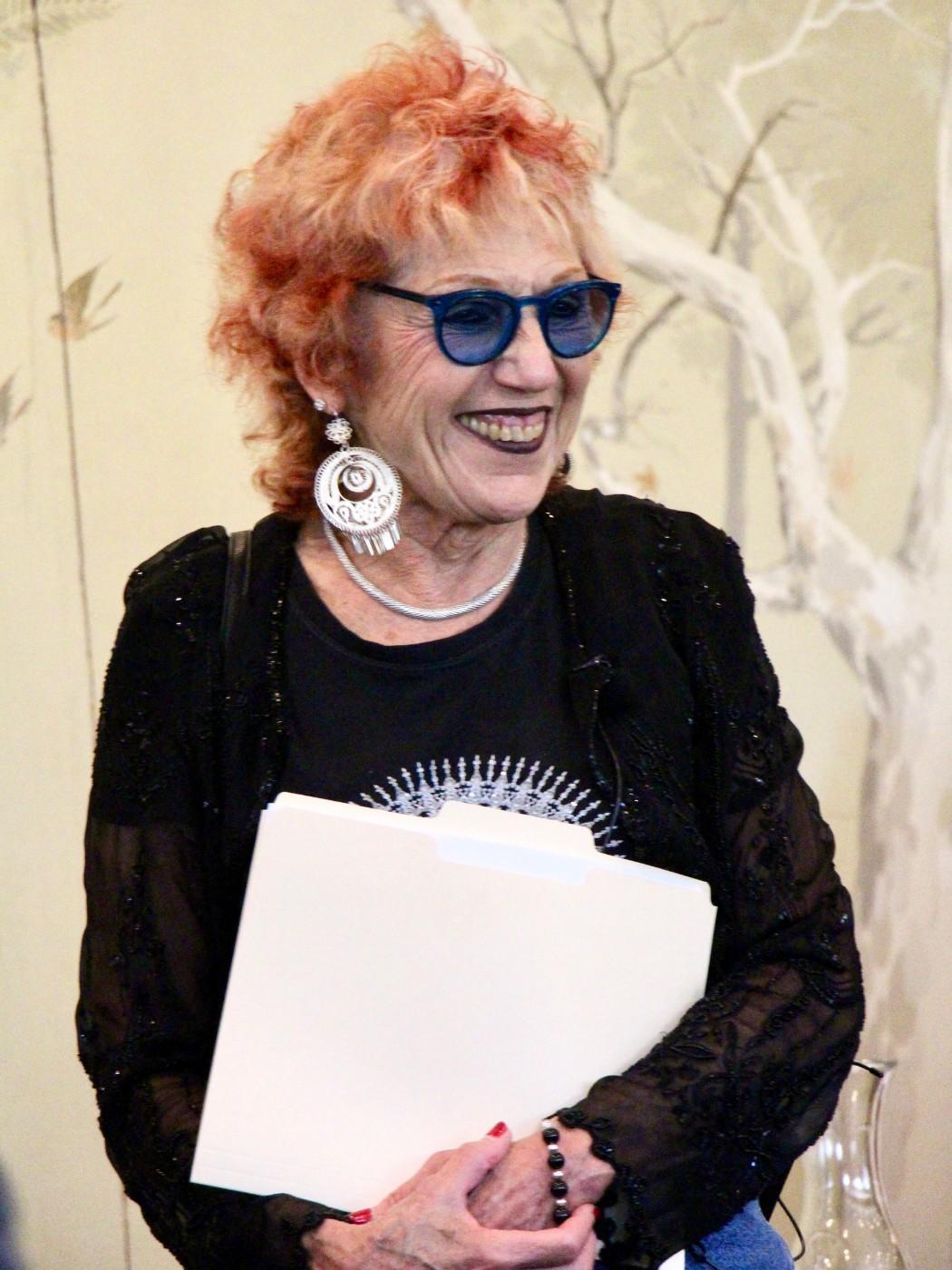

At the age of 80, Judy Chicago has arrived. Next year, she will have her first-ever retrospective at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. And last year she enjoyed a survey of her work, Judy Chicago: A Reckoning, at Miami’s ICA, coinciding with Art Basel. There, she sat for a popular Q&A with gallerist Jeffrey Deitch who is bringing Judy Chicago: Los Angeles, a wide-ranging look at her early work, to his gallery in Hollywood beginning September 7 through early November.

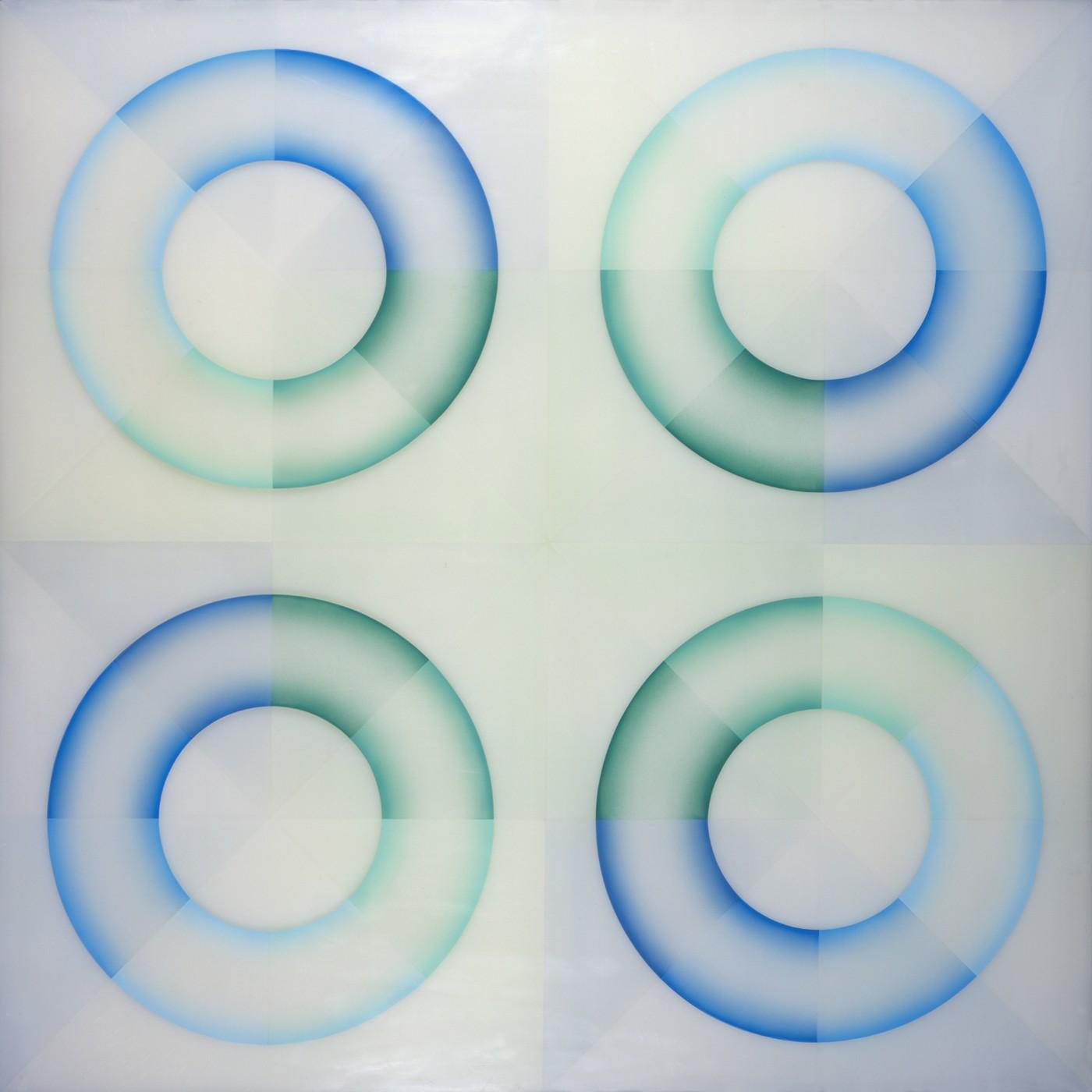

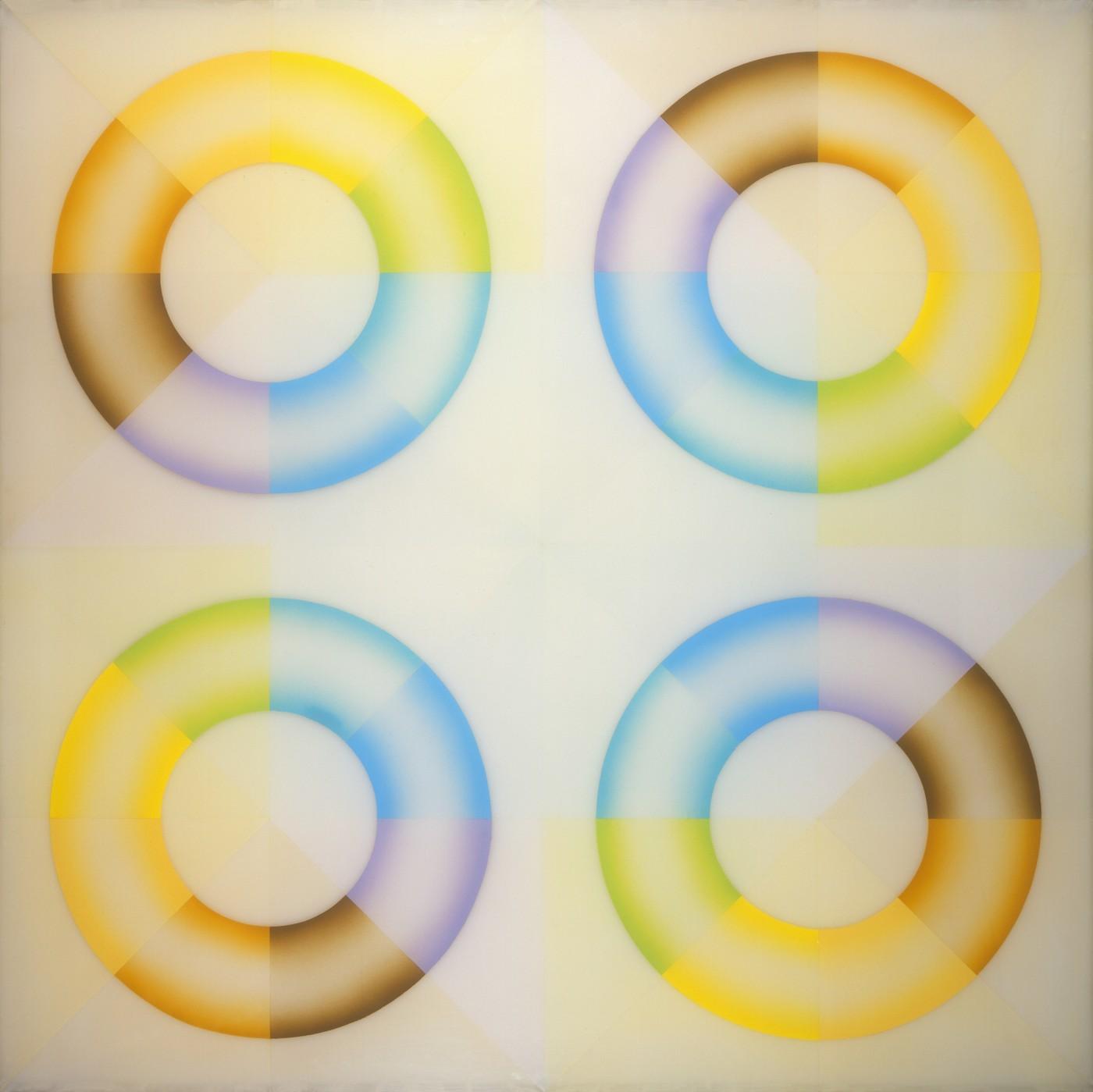

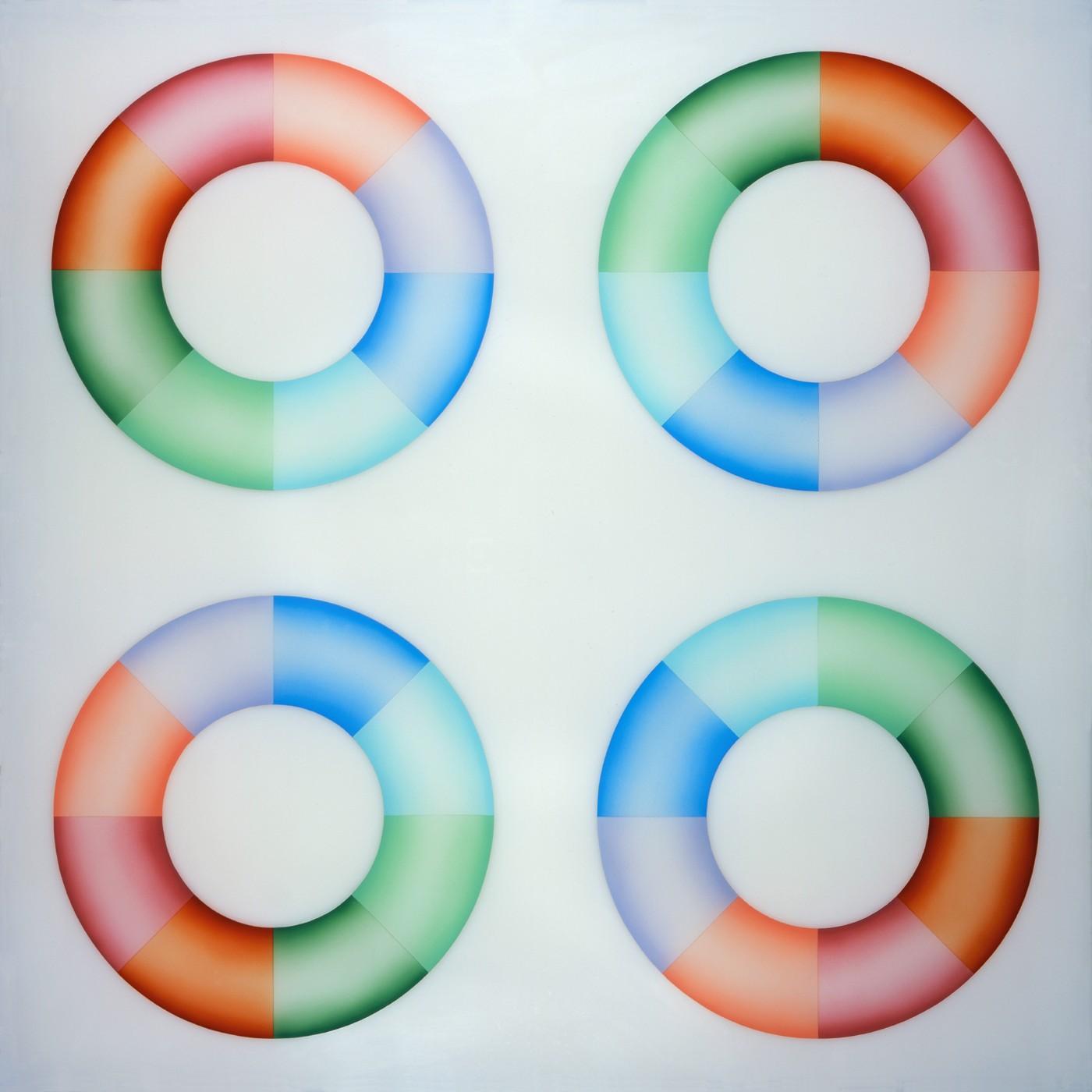

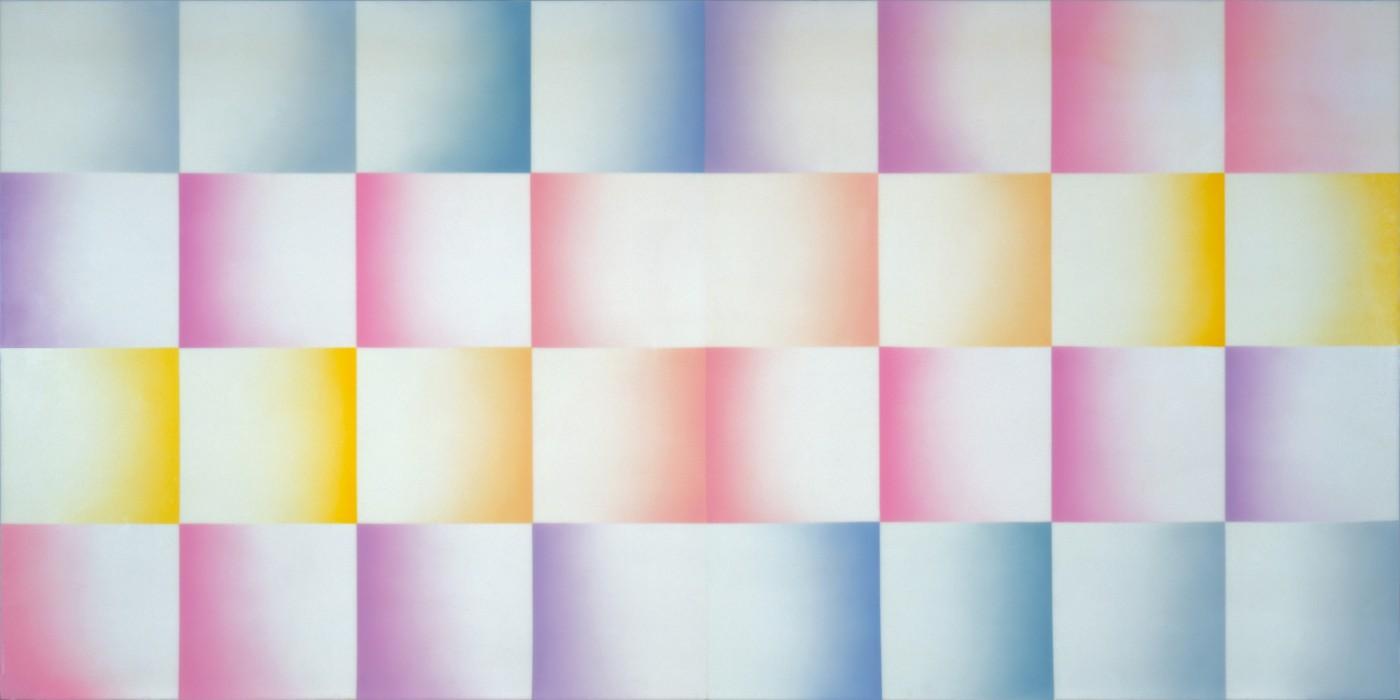

“My first decade and a half of practice in Southern California, it was incredibly difficult and challenging cause the art world was so inhospitable to women,” Chicago, (born Cohen) tells Art & Object from her home in Belen, New Mexico. “Still, within that period I built the building blocks of my career, my formal ability, my color systems, the scale I was interested in working, the level of ambition, the level at which I wanted to try and make a contribution. I had a burning desire to make art. I had a lot to say. And I made making art my reward.”