Recent work published by an international team of researchers from Greece, Spain, and the United States has corroborated the original theories from 1977 about who the deceased were, but now presents new arguments about who exactly was where.

The Great Tumulus, one of many monumental man-made burial mounds at Aegae, contains four burial chambers all dated to the 4th century BCE. Tombs II and III consisted of two monumental vaulted chambers and were unlooted, well-preserved, and contained an incredibly rich collection of objects.

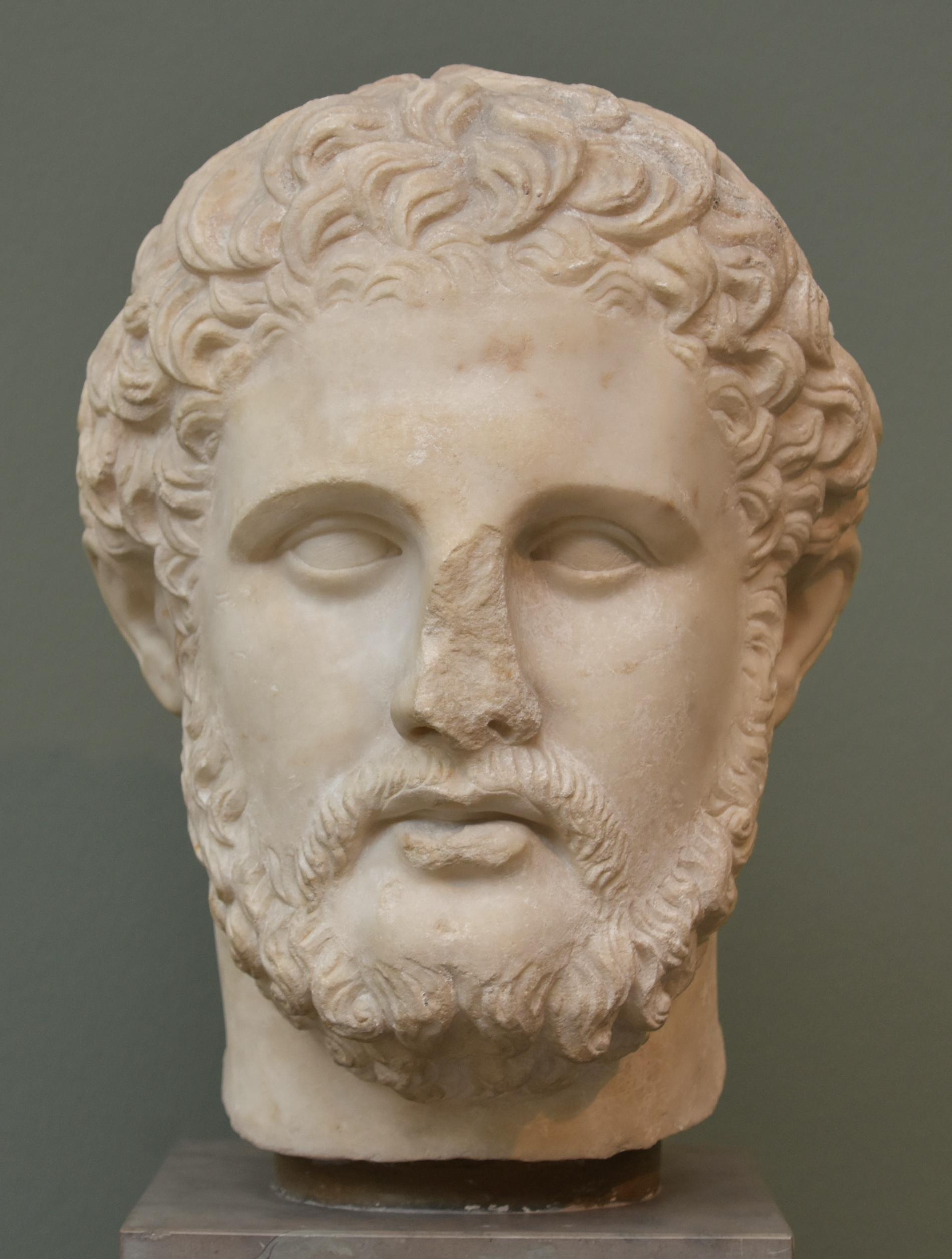

Tomb I was a smaller cist tomb and had been looted sometime in antiquity. Tomb IV, another monumental tomb, was also disturbed in antiquity. Manolis Andronikos, director of the 1977-78 excavations, initially concluded that Tomb II must have belonged to Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father; Tomb I to Alexander’s less famous half-brother, Arrhideaeus; Tomb III to Alexander IV; and Tomb IV to Cassander (King of Macedonia after Alexander IV’s death).