The longest aqueduct was 91 kilometers; the one with the largest capacity could supply 190,000 cubic meters of water a day. Reliant on gravity, aqueducts had to run downhill from their spring or lake source. To achieve this, they took snaking routes over the geography; where necessary, paths were hacked through hillsides and bridges built to span valleys. Maintaining a steady gradient over the length of the aqueduct was crucial: too steep and the channels would burst, too gentle and the water wouldn’t flow.

Parco degli Acquedotti

Forget the "idle" pyramids of Egypt and the "useless" temples of Greece, the aqueducts of ancient Rome are the "most marvelous structures in the whole world." So claimed Roman writers in the 1st century AD. Not only were such monuments impressive and practical, they were understood as challenging Nature itself by taming the flow of water. These marvels of Roman engineering can still be seen today.

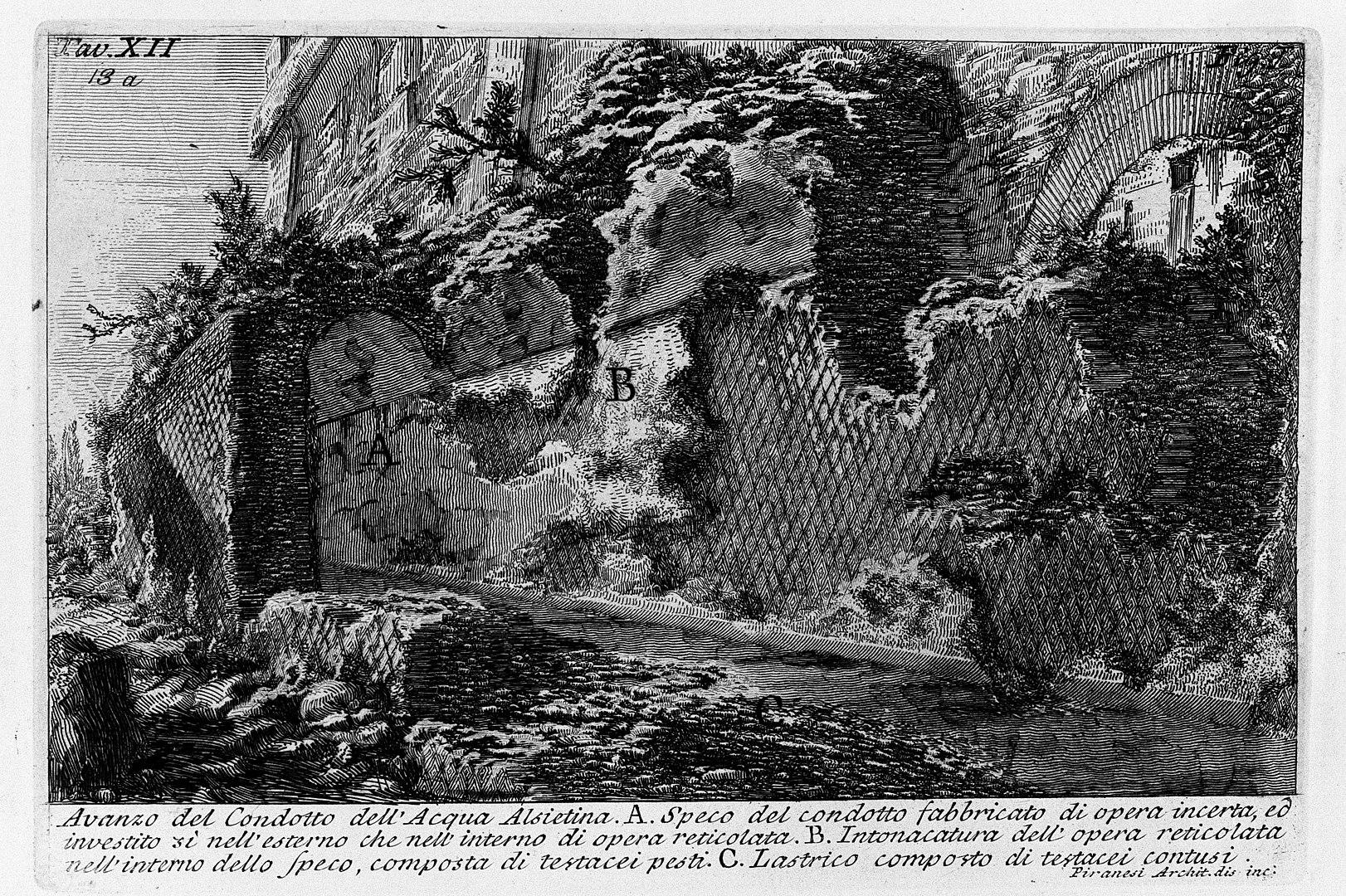

Eleven aqueducts, constructed over a 500-year period, fed the ancient city of Rome. While much of the water was for drinking, the increased supply also allowed for extravagant public fountains and private ornamental garden features. The Aqua Antoniniana supplied an enormous 10,000 person bathing complex built by the emperor Caracalla, while the Aqua Alsietina was used to fill a water-based arena (naumachia) on which sea battles were fought for entertainment.

19th Century Piranesi etching of Aqua Alsietina

An ancient aqueduct in the Roman countryside

For most of their length aqueducts traveled underground, only emerging when they approached the lower-lying city. When the channels did appear, it was in spectacular style on raised arches. Traces can be found scattered across the countryside and amid the urban sprawl for miles in all directions around Rome. However, there is also a dedicated park just beyond the city walls. Easily reachable by public transport, the open, green space of Parco degli Acquedotti allows visitors to get up close to and stroll amidst the ancient remains.

Aqua Claudia

The most impressive monument in the park is the Aqua Claudia. This aqueduct was started by the emperor Caligula, but after his murder, his uncle and successor Claudius completed and named the work after himself. For sixteen of its total 68-kilometer length the water was carried on imposing arches of volcanic stone blocks, stretches of which still survive.

Near the outskirts of the ancient city (now a short walk from the main railway station Termini), at the point where the Aqua Claudia crossed two roads, the arches were monumentalized further. Built using white travertine limestone, the blocks were deliberately carved to look unfinished, giving it a rough, natural aesthetic that creates a patchwork of shadows when caught by the light. The structure imitates a triumphal arch; but rather than celebrating the defeat of an enemy of Rome, this monument symbolizes the conquest of Nature.

Porta Maggiore, Aqua Claudia

Three inscriptions are carved into the attic of the arch. The first praises Claudius for building the aqueduct, but the second records repair works carried out by the emperor Vespasian, claiming that the aqueduct had fallen into disrepair just ten years after it was finished. The third inscription speaks of yet another restoration only a decade later by Vespasian’s son Titus. It is a reminder of the ongoing maintenance that aqueducts required as well as the inevitable difficulties that accompany complex engineering projects.

Rome’s aqueducts went out of use as the city declined. In the 2nd century AD, Rome’s population was approximately a million people, but by the 6th century AD, it had fallen to perhaps ten percent of this. Fewer people meant less water was needed. The water supply also suffered irreparable damage in 537-538 AD, when a Byzantine army was besieged in Rome by the Goths. The attackers are said to have cut the water channels and the defenders, worried that the conduits provided a covert route into the city, walled them up.

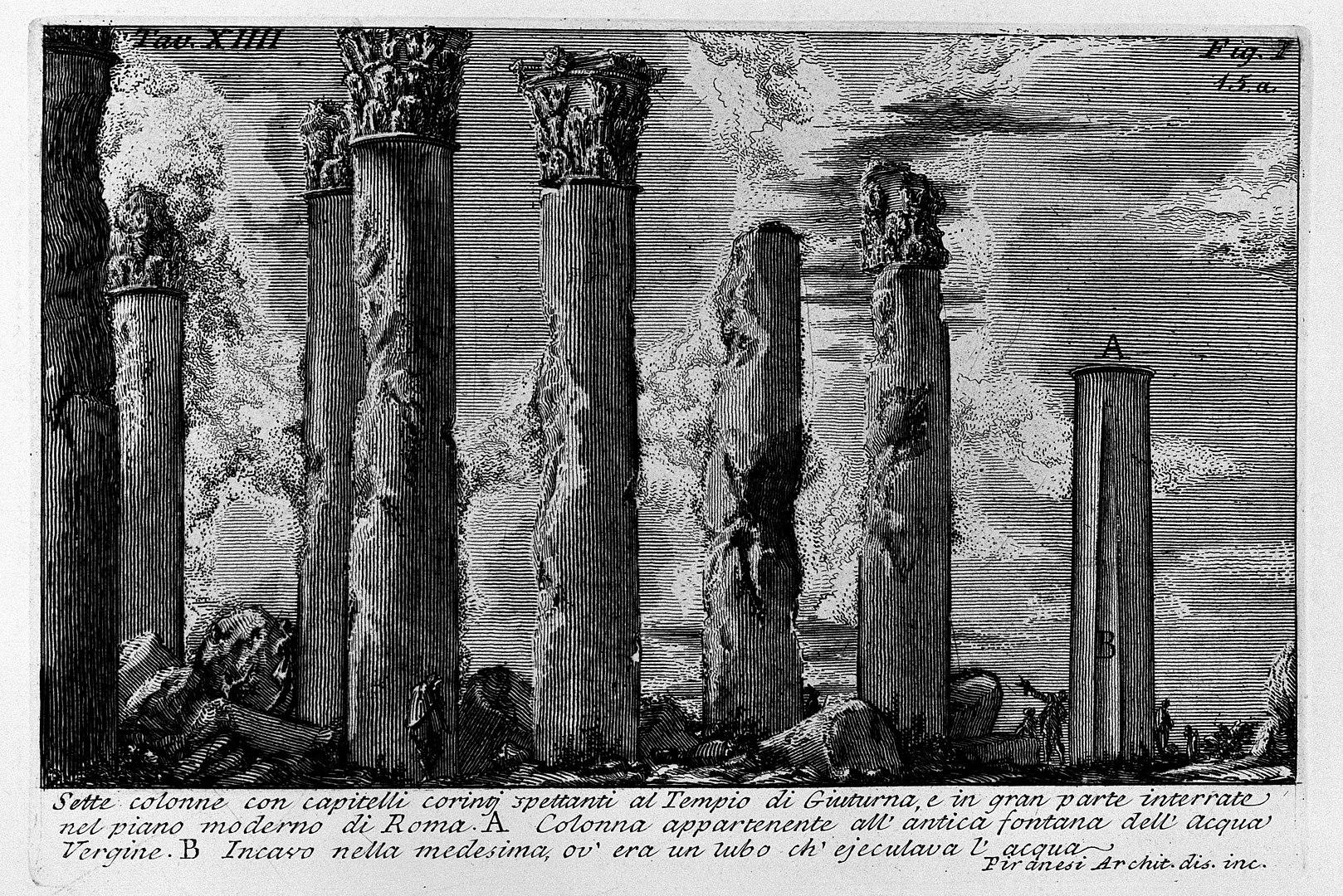

19th Century Piranesi etching of the Aqua Virgo

The only aqueduct to have remained in constant use since antiquity, more or less, is the Aqua Virgo. Constructed by Marcus Agrippa–the emperor Augustus’ right-hand man–in 19 BC, the flow of water was reduced to a trickle by the time of the Renaissance. A major restoration by Pope Pius V in 1570 returned a plentiful supply of fresh water to the city and led to the creation of new, ornate fountains, including "the old boat" at the bottom of the Spanish Steps as well as the famous Trevi Fountain (although the fountain as it currently stands, that which Anita Ekberg danced in and Frank Sinatra sang about, was not completed for another two centuries).

In Rome, modern apartments are constructed in an ancient aqueduct arch

In 2017, the department store Rinascente opened on Via del Tritone in the center of Rome. During the renovation of the building, the remains of an ancient city block were discovered. Today, go into the store, walk past the designer handbags, take the escalator down, navigate through the coffee pots, and fifteen arches of the Aqua Virgo can be found, illuminated by a new laser light show. The marvels of Roman engineering can still be seen throughout the city, if you know where to look.