A famous example occurred in the dead of a late midsummer's night in 2000 when Goldsworthy and his crew placed thirteen six-foot snowballs at various locations on London’s city streets, drawing a set of reactions ranging from slightly irritated surprise to awe as people encountered the huge white orbs the following morning. The snowballs had been created near his home in Scotland over two winters, kept in cold storage, transported to London and left to melt revealing the detritus; twigs, sheep’s wool, pebbles, etc., from the rural landscape where they were made. They served as a clarion call to global warming. The London project reveals a subversive humor that may not be evident to those who know Goldsworthy primarily through the award-winning 2001 documentary film, Rivers and Tides, a beautifully realized meditation on nature and the inevitability of change.

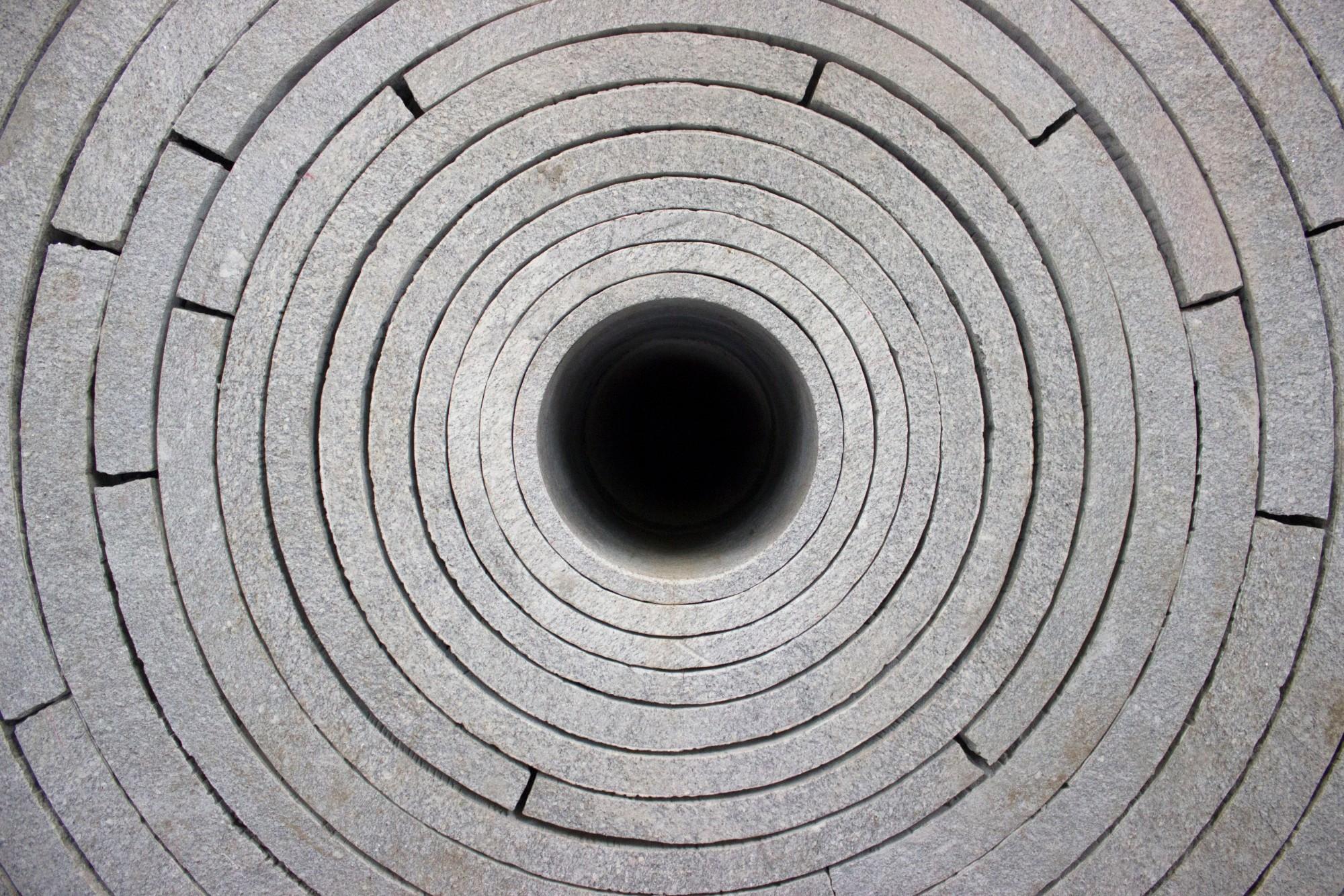

Andy Goldsworthy, Watershed (detail), 2019. Granite, Corten steel, spruce pine wood. Installation at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.

"I love drain holes," declared Andy Goldsworthy, "you know, that interface between what we see on the surface to below... Nobody looks at them, except me.” It was July 9, 2019, during the installation of Watershed, Goldsworthy’s first publicly accessible permanent site-work in New England at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts and the artist was being interviewed on local radio station WBUR.

The plan began ten years ago when the deCordova extended an invitation to Goldsworthy to create a project for their grounds, an idyllic thirty-acre setting founded in 1950, twenty-miles from downtown Boston. Since its beginning the museum’s focus has been to showcase the work of living artists, filling what was a huge void in the local Boston art scene. Given Goldsworthy’s notability as a much-in-demand international figure known for creating ephemeral earthworks documented in meticulous photographs, this would be the deCordova’s most ambitious and expensive acquisition to date. At the time that the invitation was extended Goldsworthy had been working with ice and giant snowballs, sometimes placed in incongruous environments.

The original deCordova proposal titled Snow House harkened back to historic New England icehouses. Goldsworthy’s plan required a huge snowball to be rolled each winter, presumably by an enthusiastic group of volunteers and museum staffers, placed inside a rough-hewn stone structure and left undisturbed until a summer day when the door would be opened and the nine-foot diameter snowball, exposed to the elements, would take approximately five days to melt. The concept for Snow House was a departure for Goldsworthy in that it combined his well-known transient work with man-made architecture and intentionally crafted materials.

Snow House was commissioned in 2009. However, when John Ravenal, former associate curator of 20th century art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, arrived at the deCordova in 2015 as the new executive director only two-thirds of the funding for the project was in place. He described his solution in a recent interview for Art & Object. “I came to understand that the [museums’] financial situation overall was much more fragile then I previously thought…I put a lot of effort into researching partnerships and discovered The Trustees, a well-established Massachusetts based cultural organization with a focus on land preservation. We have strong mission alignment, and not much duplication.” As Ravenal worked on a merger with The Trustees he, along with deCordova curator Sarah Montross, realize that Snow House was being derailed by logistics. Goldsworthy was not able to conform the project to the stringent Massachusetts building codes required for a publicly accessible permanent structure.

Perhaps a bit chagrinned, but undaunted, Goldsworthy speaks a lot about “learning to accept loss” and in order to grow artistically “failures have to hurt.” Seizing upon this setback as an opportunity he went about searching for a new concept and found it in a drain hole in the parking lot. With the original secluded hillside site in mind Goldsworthy designed an outlet hole connected to the upper level drain through which water would flow dependent on the intensity of the rain, or snow melt. The hole, surrounded by a wall of concentric circles of hand-chiseled granite quarried locally by master cutters at Le Masurier Quarry, Inc. in North Chelmsford, MA becomes the focal point of a corrugated corten steel roofed nine-by-fifteen foot stone shelter built around it.

Now titled Watershed, the structure has a sanctuary-like feel with stone seating inside for contemplative meditation. On a rainy day the site comes alive with the sound of rain on the roof. “Then if it really carries on, the water will begin to trickle from the hole. And if they get a really good storm, that [rain] will start to flow with a considerable force,” Goldsworthy predicted. “So there’ll be this kind of threat. You'll be threatened inside the building and I quite like that sense that nature doesn't stop at the walls of a building.” Over time, mosses will build up as the water flows down the wall and back through a carpet of gravel into the ground.

Andy Goldsworthy's Watershed installed at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

Curator Sarah Montross was impressed by the friendliness and collegiality of the Scottish “wallers,” artisans skilled in drywall stone construction that Goldsworthy has worked with for decades. “It was magical watching them work as a well-choreographed team.” Montross felt an excitement building up to the opening of Watershed. “It is a major step for us. This will affect the nature of our park, creating a new orientation to our grounds, bringing the public to an area less traveled.” Although Goldsworthy explores new territory in Watershed it continues his concept of “flow,” celebrating constant movement as a life force and the inevitability of change.