The ATHAR Project, which is comprised of "experts digging into the digital underworld of transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime," recently shared videos taken from Facebook showing thieves at work, many of whom risk their lives to excavate buried sites. The project was formed in part in response to conflicts like the on-going war in Syria and the unrest of the Arab Spring, which ISIL and low-level thieves take advantage of. The chaos and destruction of Syria's civil war has resulted in the mass looting of precious antiquities, as well as the all-out destruction of some of humanity's greatest historic sites.

In new community guidelines released this week, Facebook announced a new policy meant to halt the sales of looted artifacts on its platform.

The new rules follow a major report from the BBC last year, which detailed the mass sale of illegally acquired archeological goods. Developed with The ATHAR Project (Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research), a group of anthropologists that tracks the illicit sale of antiquities online, the report uncovered ninety-five Facebook groups with over 1.9 million members who traded tips for looting ancient sites and attempted to sell their wares.

As the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic continues has spread, more and more people have seen their livelihoods affected. Some of these folks have inevitably turned to crime to make ends meet. In April, a thief made off with a Van Gogh painting, stolen from a shuttered Dutch museum. In North Africa and the Middle East, looters of ancient sites have taken advantage of distracted authorities to nab more historical treasures, leading to an increase in activity on the Facebook groups used to sell these goods.

Screenshots of antiquities offered for sale on Facebook

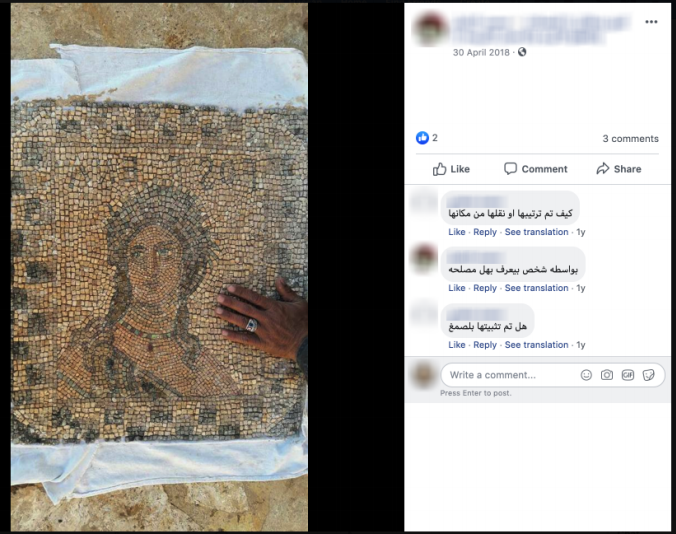

Screenshot a mosaic offered for sale on Facebook

Facebook says they shut down forty-nine groups selling antiquities last year, but the notoriously unregulated site struggles to stop all illicit activity. Though they have previously had a site-wide ban on the selling of stolen goods, the ability of the platform to enforce this policy is limited to blatant rules violations.

It is unclear if this new commitment to stopping illegal sales will result in any real change. To regulate much of the site's content, Facebook relies on a combination of reports from users and algorithms. This approach has a mixed effect and may generate too many or too few reports, which must then be addressed by a limited staff of regulators.

The new rule bans "content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts." Most often these items are coins and small ceramics, though mosaics and full and partial mummies have been offered.

These precious objects will join a black market of goods that could eventually enter the mainstream. Some of them may be sold to unwitting buyers, like the President of Hobby Lobby, who recently had to return works he purchased of dubious provenance. Others may be kept by collectors or used in international money laundering schemes conducted by terrorist and crime organizations.

The looting of these objects represents a major loss to the cultural heritage of these nations, and to humanity as a whole. Untrained thieves damage goods and sites as they excavate them, and are unable to properly care for these precious objects.

Though the new Facebook policy is a step in the right direction, there is still much work to be done to stop the destruction of these sites and the goods found in them.