Part of the Indiana Jones problem is that he is the most, if not the only famous archeologist in mainstream media. Thus, he represents the bulk of most people’s exposure to archeologists and what the job supposedly entails. As an archeologist, this author has observed that the most common responses one hears upon sharing one’s profession fluctuate between, “Oh, like Indiana Jones!” and “Isn’t that studying dinosaurs?” Both of these, one could argue, are similarly incorrect.

Archeology is an interdisciplinary study that encompasses any material aspect of human cultures and societies, both past and present. There is no one way to be an archeologist and research can span a wide realm of topics from the Neolithic remnants of early human settlements to the trash and refuse of modern cities. Some archeologists work in labs, some in museums, and some in the field.

No matter where archeologists work, they adhere to scholarly moralities of recording findings and to the knowledge that what they study does not belong to them (nor does it always belong in a museum).

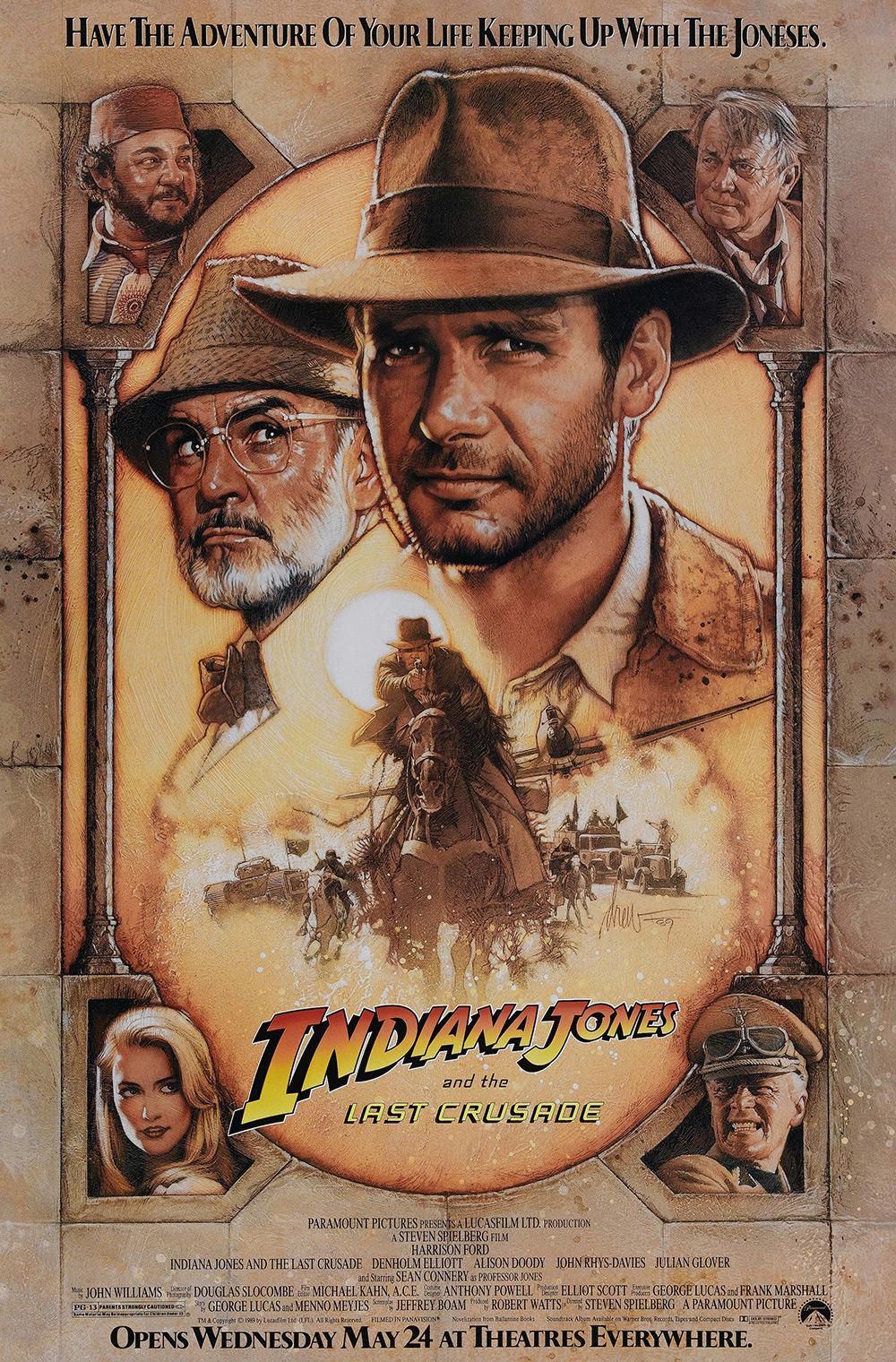

This is where Indiana Jones begins to lose credibility. Throughout the entire franchise, it seems impossible that anyone could find an instance in which the man makes a note of any kind for the purposes of preserving data rather than for fueling his own treasure hunt. And no, the rubbing of the shield in Last Crusade doesn’t count.