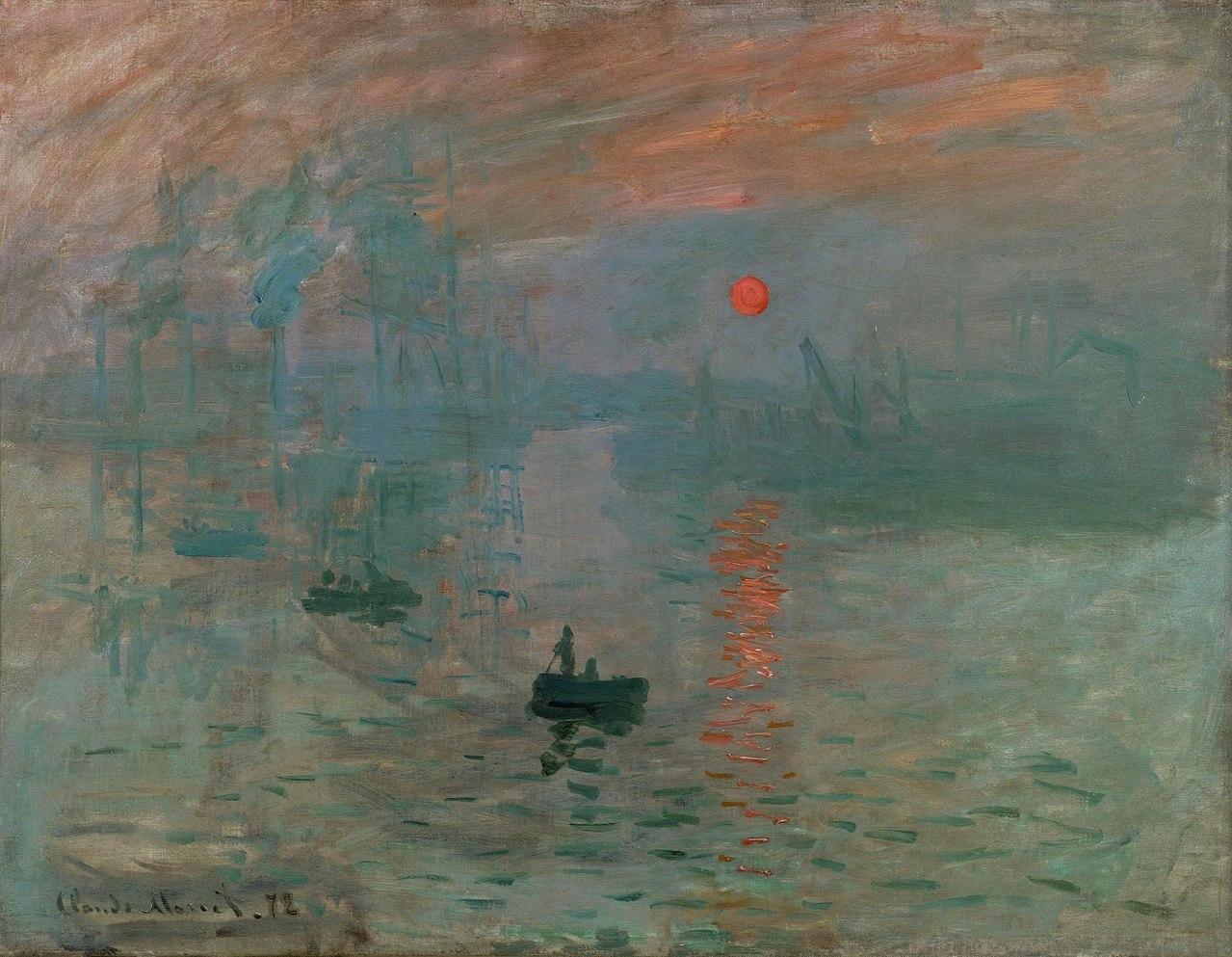

The exhibition received mixed critical reviews, with a famously biting take on Monet’s Impression, Sunrise from French critic, painter, and humorist Louis Leroy. In a review entitled “The Exhibition of the Impressionists,” Leroy wrote off the painting as nothing more than an unfinished sketch and concluded, “wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape”. The public as well as the group of artists themselves quickly adopted the term Impressionists, characterized by their utilization of bright, synthetic colors; short brushstrokes; and emphasis on the effects of light.

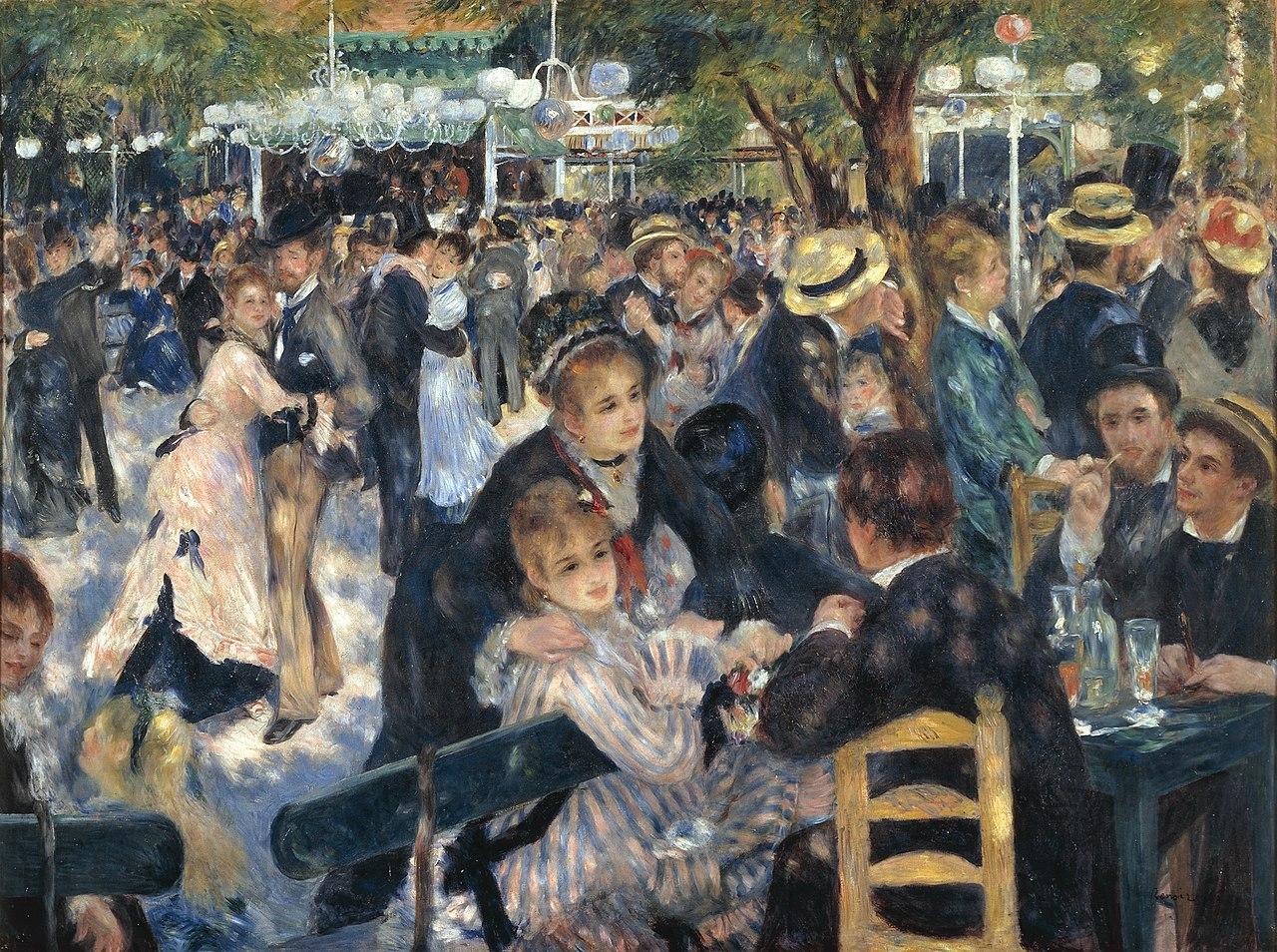

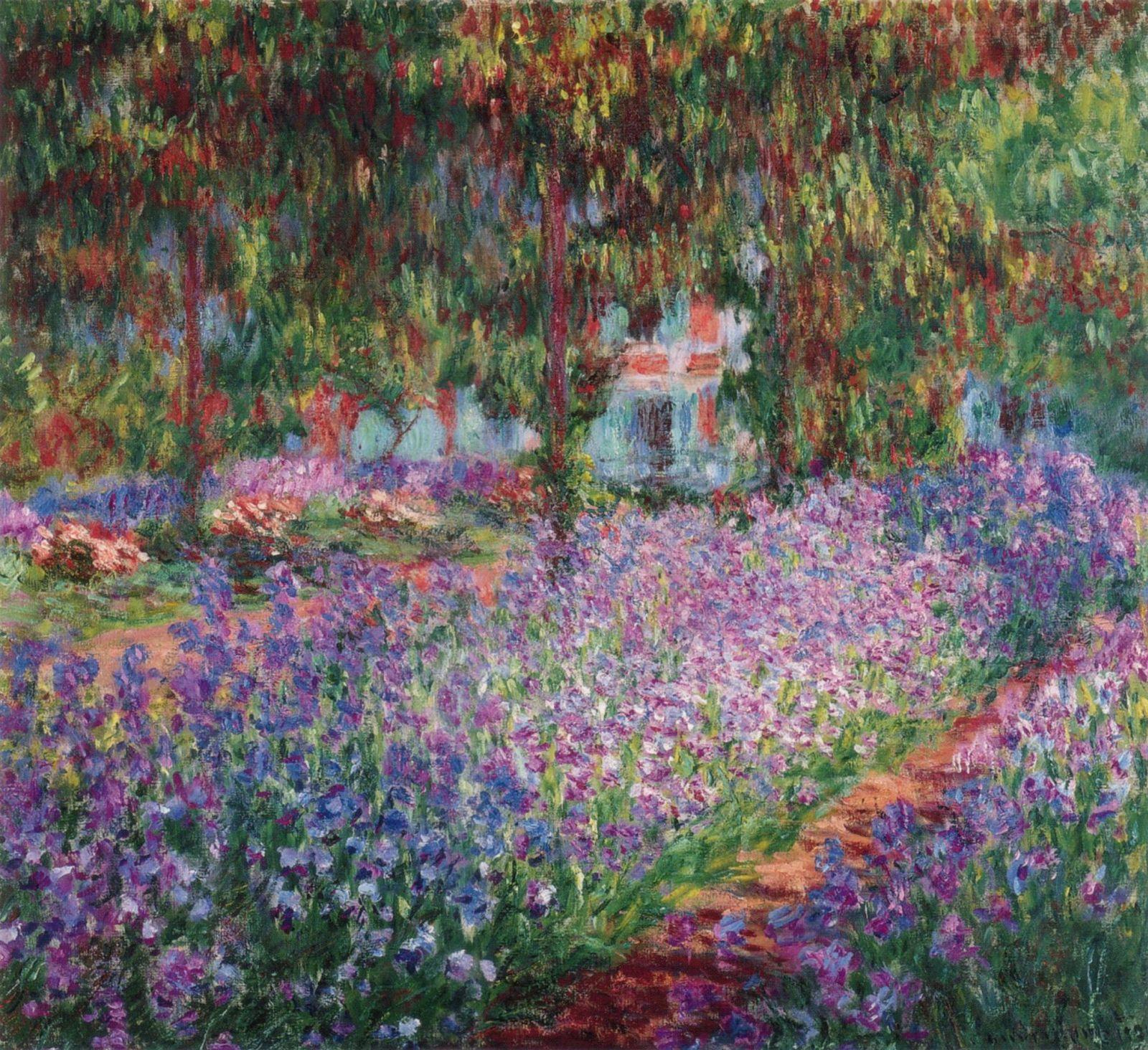

The Impressionists generally painted ordinary human subjects in rural or urban settings. They typically aimed to create a snapshot of the scene rather than a precise depiction. The use of short, thick brush strokes helped to capture the essence of the scene—an “impression” of the subject according to the artist— rather than its details.