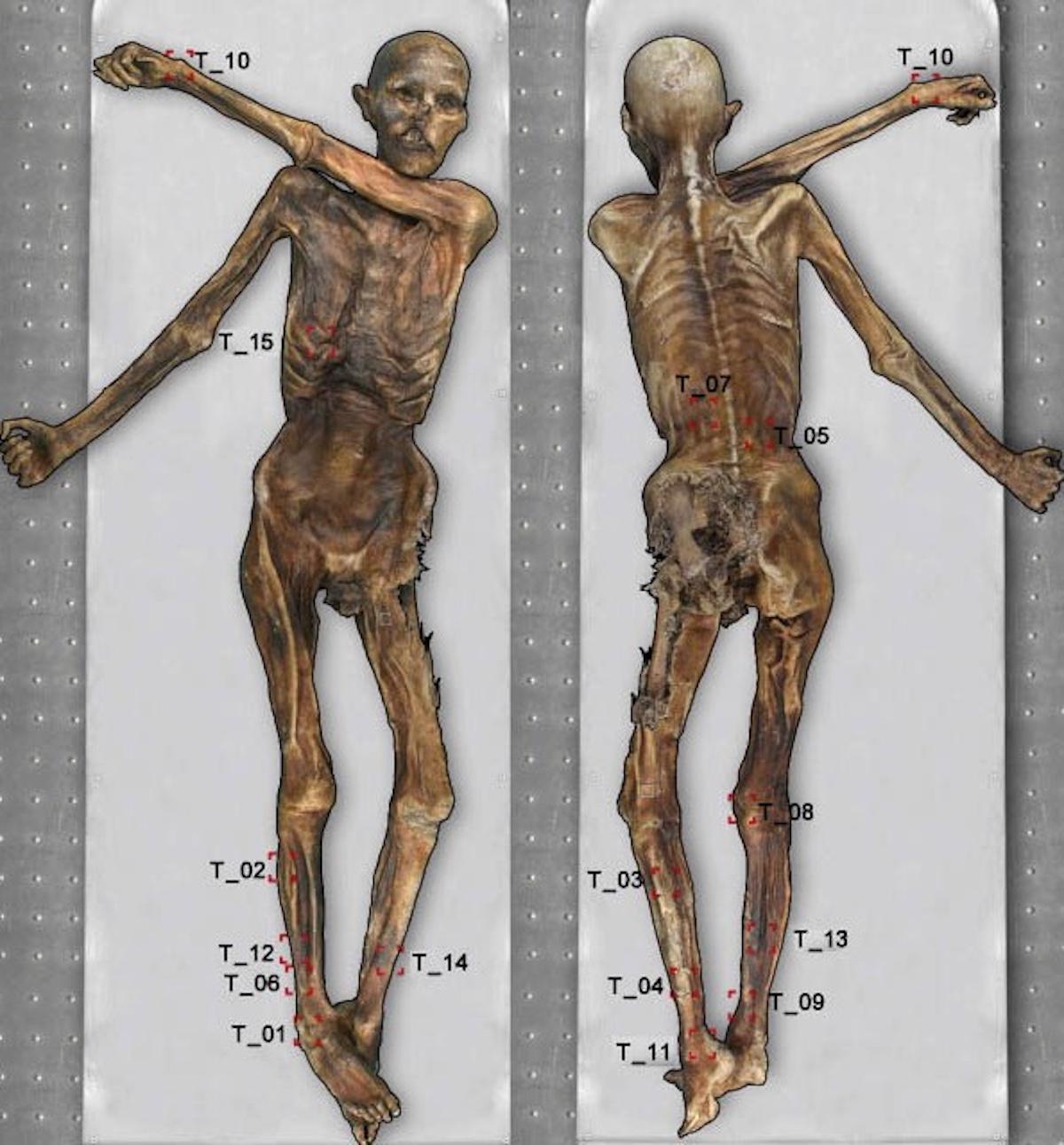

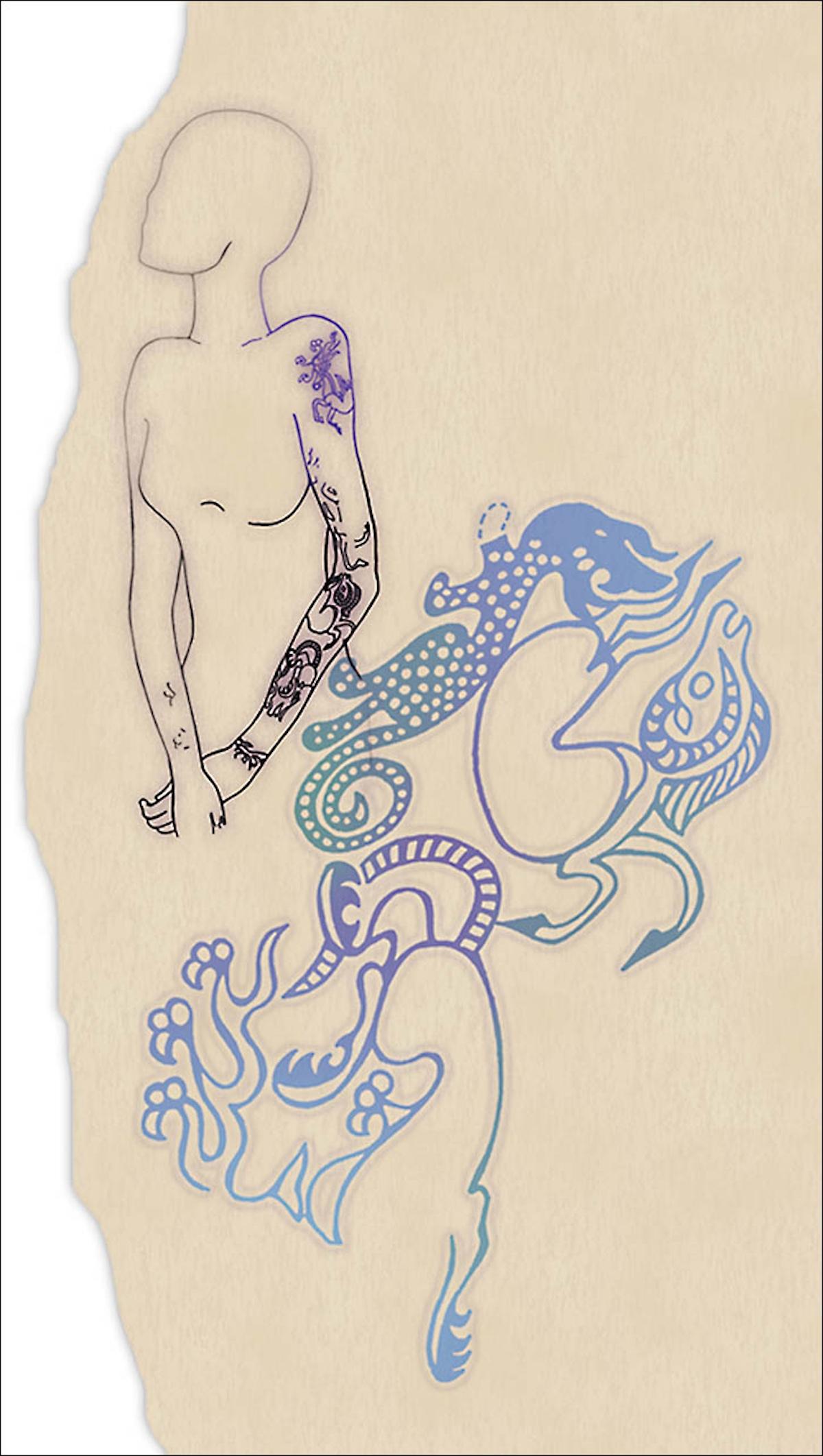

These, and other related materials, are extremely poignant in helping us understand the history and archaeology of tattoos, however, our best evidence has come from actual bodies preserved through extraordinary circumstances.

Processes of preservation are typically not kind to human bodies; more often than not, archaeologists recover little more than the bones of the deceased in their final resting place. Much of this has to do with both how a body is buried and where. In the ancient world, coffins, sarcophagi, and other elaborate tombs that could protect human remains were the burial habits of those with enough wealth to afford them. Even cremation during certain periods was often considered an ostentatious funerary rite as the amount of wood required to burn a human body completely was too expensive for the average person. Thus, many burials in the ancient world were inhumations in the ground accompanied by whatever goods those burying the deceased chose to place with the body.