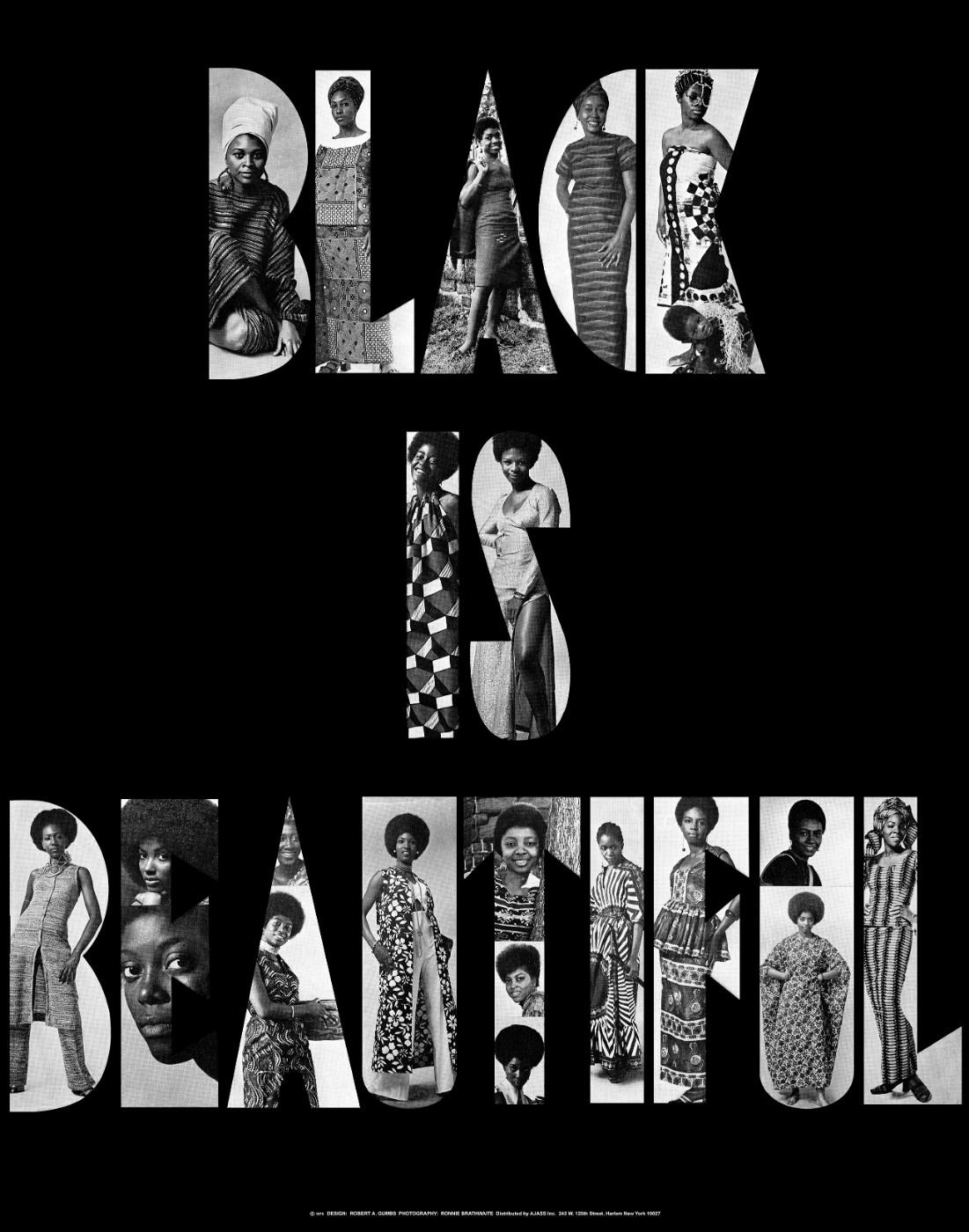

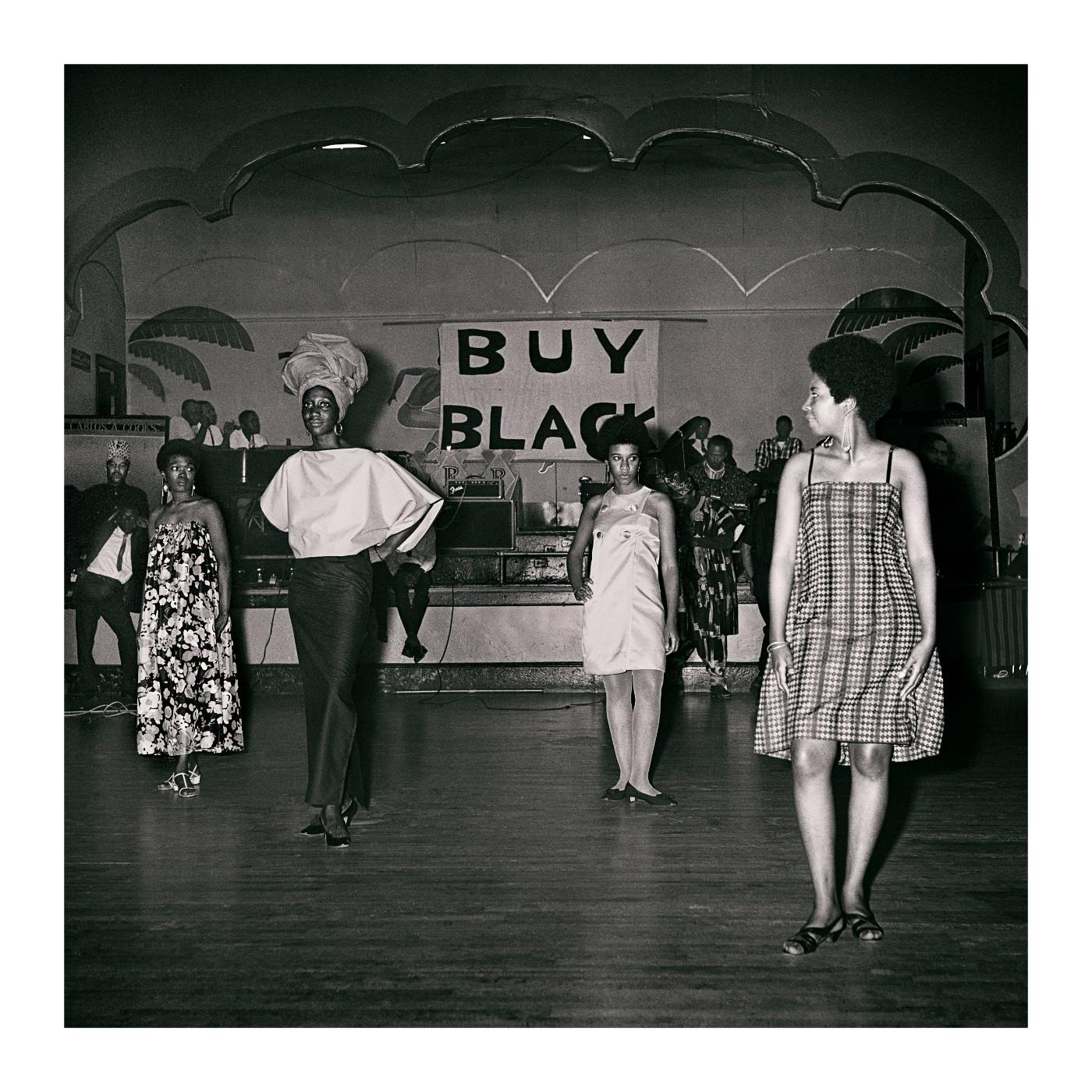

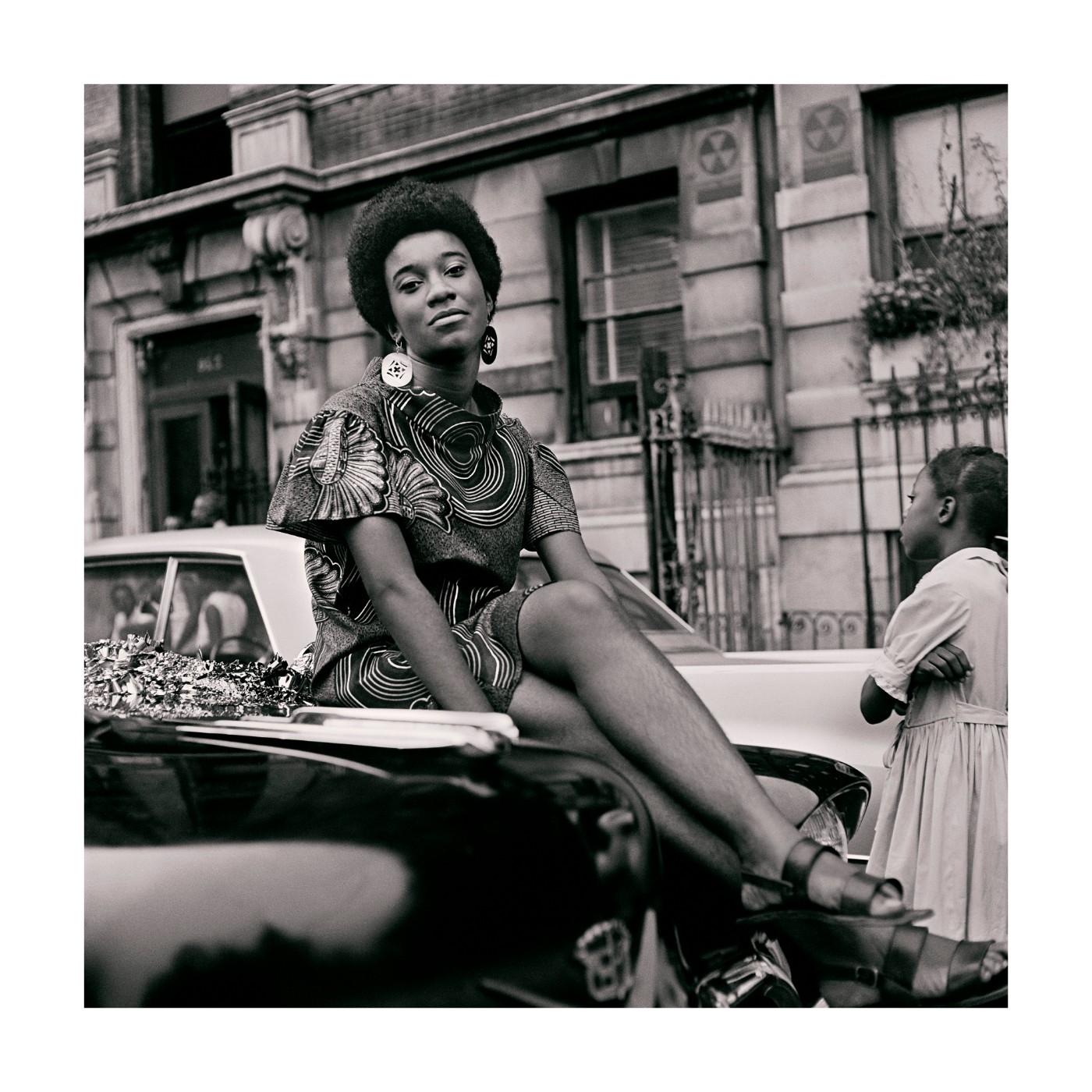

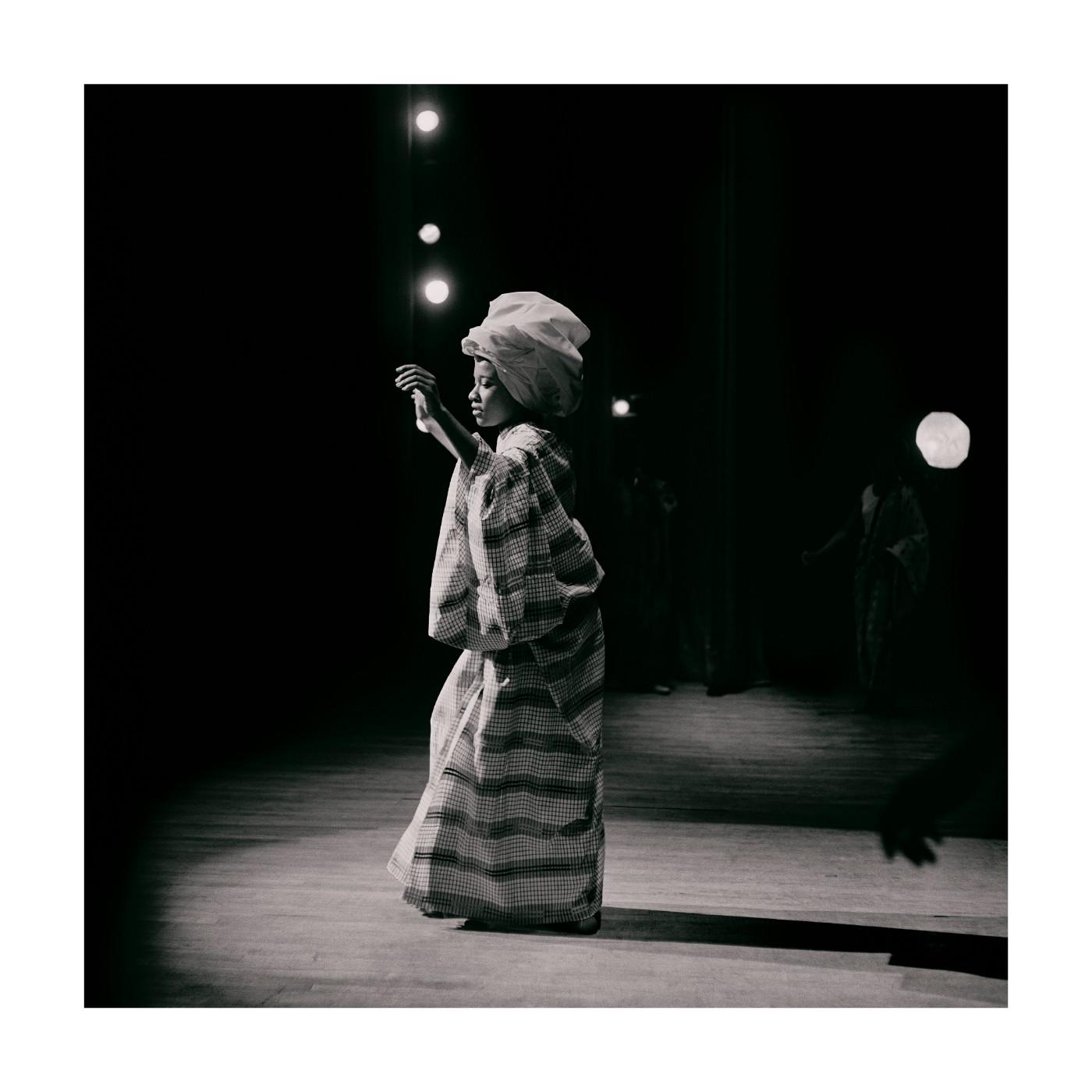

Such transformative moments, big and small, make up the core of the new show, Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite, at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles through Sept. 1, curated by his son, Kwame Jr. On display are over 40 black-and-white images of everyday people as well as jazz legends like Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Dizzy Gillespie or Art Blakey taking five with a smoke and a drink, as well as the beautiful ladies of Grandassa, a modeling agency that featured black women, some professionals others off the street, representing a variety of body shapes and skin tones.

“This exhibition is kind of like the origin story. We really do a deeper dive into a lot of his really good early work,” Kwame Jr. tells Art & Object about the new show. “He was self-taught, so he’s kind of figuring out the ways in which he wants to shoot.”