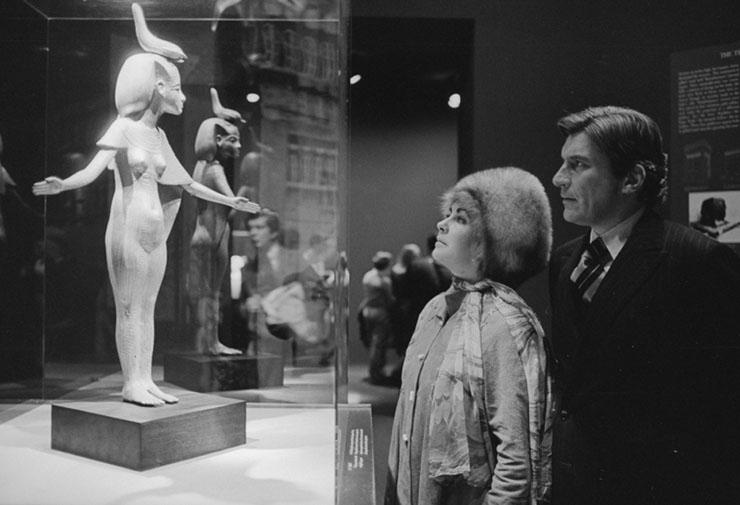

As mentioned previously, several other touring exhibitions have occurred over the decades. One of note was Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs (originally entitled Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter). The show toured across Europe and the US from 2004 to 2011 and was considered special because it mostly featured objects that were not included in the 1970s tours.

Today, 100 years after the initial opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb, King Tut’s remains and the most fragile items of the collection no longer leave Egypt.

A few years ago, a touring exhibition billed as the final time any items from the King Tut collection would ever leave Egypt was scheduled to run from 2018 to 2021. Entitled Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh, the show featured 150 items. More than sixty of these had never been seen outside of Egypt. Unfortunately, because of the pandemic, the tour’s last two stops—in Boston, Massachusetts and Sydney, Australia—were canceled.

Currently, the King Tut collection is mostly located in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Officials plan to eventually move it to the Grand Egyptian Museum which, after several years of more pandemic-related delays, is finally scheduled to open in November 2022.