Thompson’s art didn’t overtly reference racism in his art, though a Black artist raiding the cupboards of a racially exclusionary tradition was undoubtedly a loaded act, and he did limn bodies in hues that could be taken for skin tones other than Caucasian.

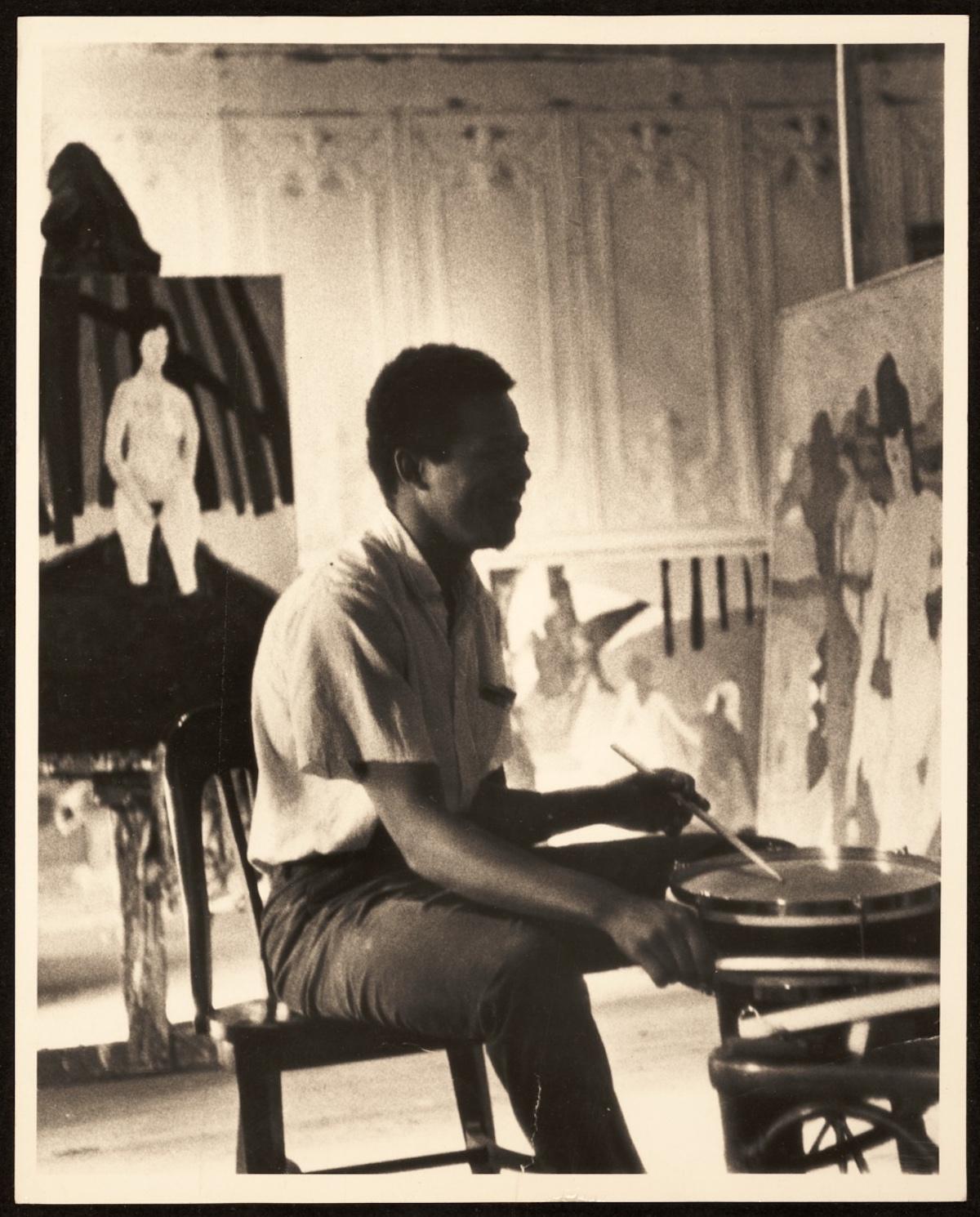

Thompson had been born in Kentucky and grew up under Jim Crow, which undoubtedly shaped his worldview. Had he lived beyond his 28 years, it’s conceivable that he might have moved towards directly addressing race, much as his contemporaries Robert Colescott and Melvin Edwards did in the 1970s and ’80s. But then again, maybe not. As it is, the show at David Zwirner offers a look into what Thompson was up to.

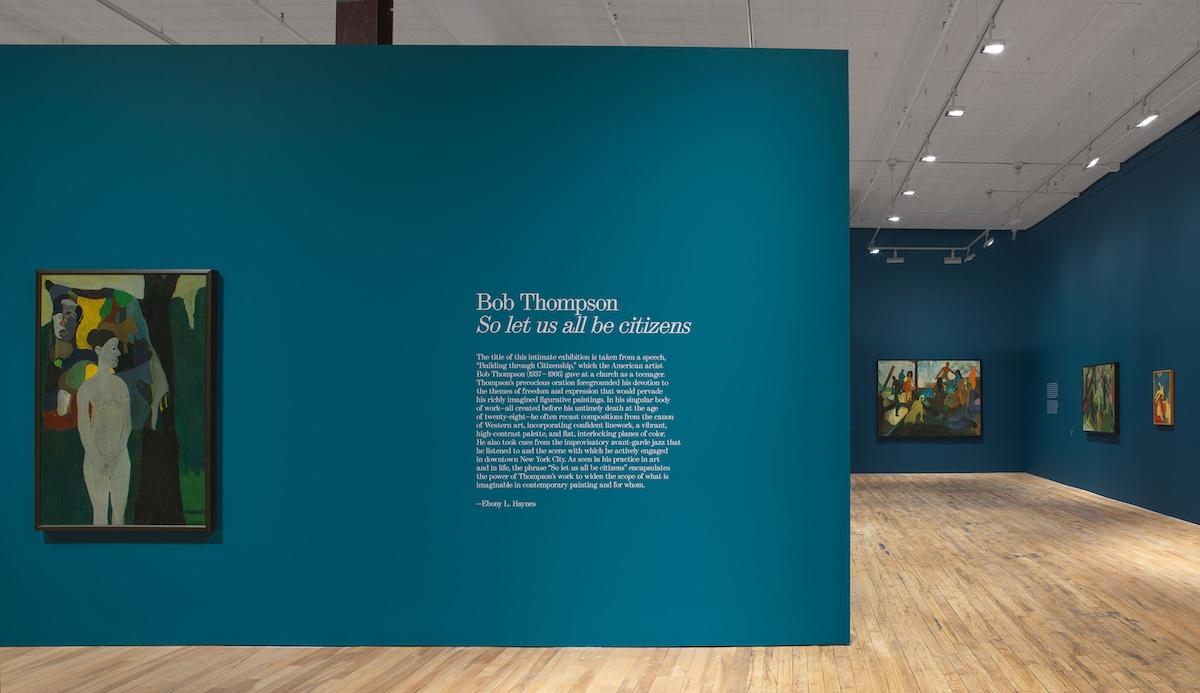

With its wall painted a bottomless shade of blue, “So let us all be citizens” at 52 Walker evinces the kind of museum-quality presentation that only a mega-gallery like David Zwirner (for which this venue serves as Tribeca outpost) can mount. The proceedings are glossed with the kind of institutional sheen reserved for retrospectives, and indeed, the paintings here are all on loan from important collections, public and private—an undertaking not taken lightly considering the cost.