The firestorm began on August 16, with a news release by the Museum, announcing that small pieces kept in a storeroom belonging to the Museum’s collections were missing. They include “gold jewelry and gems of semi-precious stones and glass dating from the 15th century BC to the 19th century AD.” The pieces were not recently on display and most of them were “kept primarily for academic and research purposes.”

An ultra-wide rectilinear stitched panorama of the Great Court of the British Museum in London, United Kingdom.

The British Museum has announced that Mark Jones, a former director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London, would be its interim director. The announcement, which was made via news release over the weekend, comes on the heels of the recent crisis in August when the museum revealed that over 1,500 artifacts had been stolen from its storerooms.

While the museum announced that an employee of the museum had been fired over the discovery of the theft, it had not disclosed a name. Greek antiquities curator, Peter Higgs, has been identified by the Times of London and the Daily Telegraph as the employee in question. Higgs is suspected of having taken uncategorized items and selling them on eBay: one item worth a reported $64,000 was offered for a mere $51.

Jones is replacing Hartwig Fischer, the German art historian who resigned on August 25 amid the scandal. Fischer, who had led the museum since 2016, initially denied any wrongdoing, saying in a statement that his handling of the allegations was robust.

But after countless news outlets called out the director, with the Times of London writing that the thefts were “a national disgrace, calling into question the museum’s own claims for its stewardship of cultural treasures, and for which it needs to give a full accounting,” Fischer resigned taking full responsibility for the incident. He said in a statement, “The responsibility for [the] failure must ultimately rest with the director.”

Room 18 – Parthenon marbles from the Acropolis of Athens, 447 BC

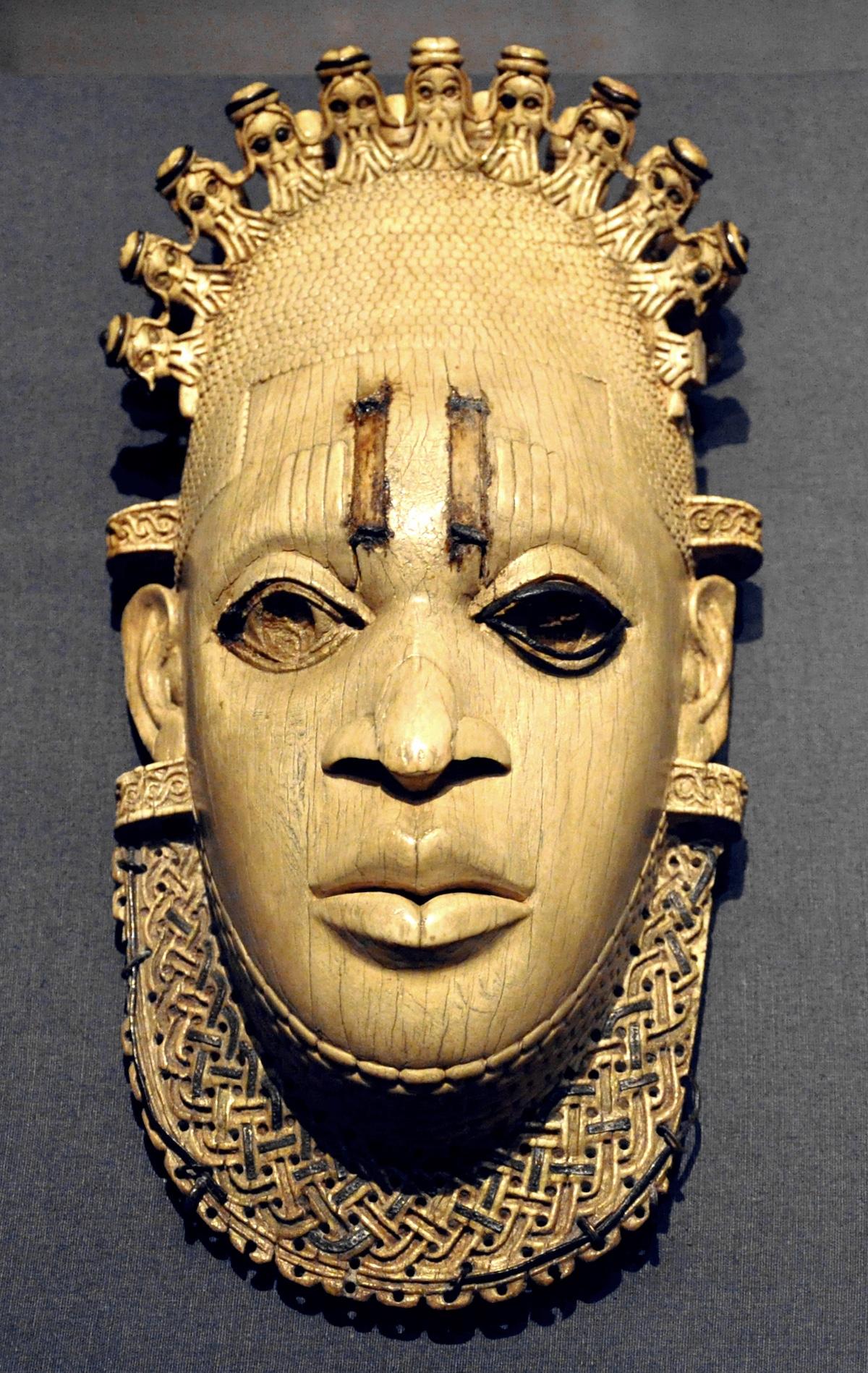

Room 25 - Benin ivory mask of Queen Idia, Nigeria, 16th century AD

The looting has shined a light on the museum's glaring inventory issues and dated record keeping system. According to their website, the online collection has 4.5 million objects—but this is only half the entire collection. In 1988, the National Audit Office issued a report stating that the museum’s record keeping was “unsatisfactory.” The report prompted other museums, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, to complete computerized inventories of their collections. But the British Museum did not. Because of these gaps in record keeping, George Osborne, the museum’s chairman admitted in a BBC interview that the gaps could be exploited. But, he insisted the museum’s treasures were safe.

Jones has some experience with such challenges. During his tenure at the Victoria and Albert Museum, from 2001 to 2011, he handled the repercussions flowing from various thefts including one involving $100,000 worth of Chinese jade. The museum responded by tightening security, replacing display cases, and improving surveillance systems.

This unsettling incident and its revelation not only raises questions about the security of priceless objects owned by the Museum but also intensifies the ongoing global debate surrounding the British Museum’s ethical responsibilities towards the objects in its possession. Many have agreed that if the British Museum can’t figure out their record keeping of artifacts that have questionable origins—including the the Elgin Marbles and the Benin Bronzes—the museum should return those parts of their collection to the nations that want them back.