The exhibition included around 100 artworks, taking over the museum’s ground floor and garden. MoMA recently published an online tour of its beloved sculpture garden; today, along with many other art museums worldwide shuttered to visitors, this virtual jaunt seems as far removed as possible from the tactile experiences visitors had there in 1943.

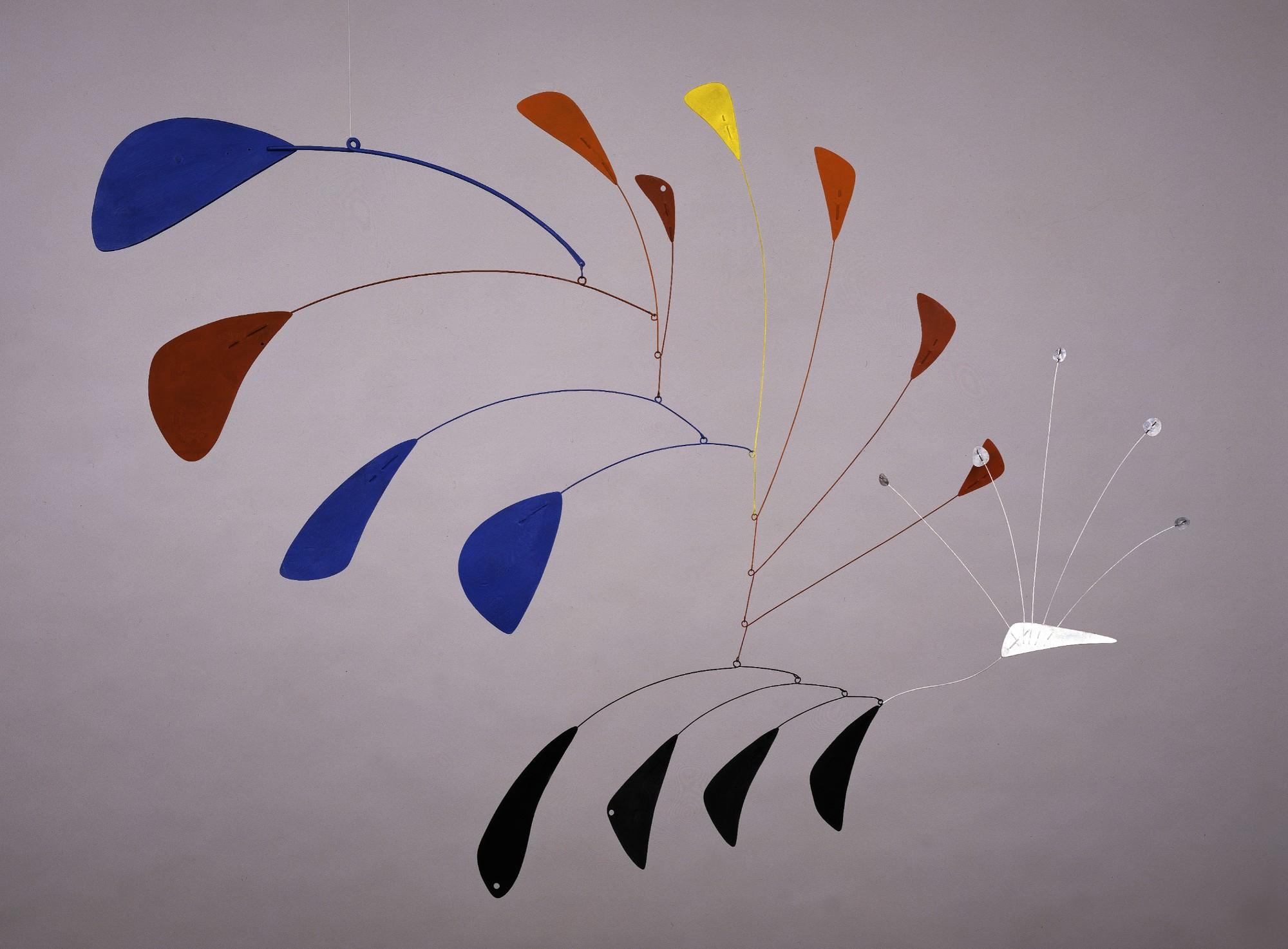

"Anyone could touch [Calder’s sculptures], move them, sway them and even push them with their feet," Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa wrote in response to the show. He was shocked by what he described as an “overwhelming absence of taboos.”

This interactivity was something Calder had been working on for over a decade, by that point. His first kinetic artworks were moved by motors or cranks, but by 1932 he shifted towards more open-ended sculptures that gave viewers a choice in how they moved.