But why host an exhibition about revealing the Gentileschi work and then not remove the veils physically? The head conservator of the project, Elizabeth Wicks, inquired in a statement. “First, the removal of the thick layers of oil paint applied by Il Volterrano less than five decades after the original could put Artemisia’s delicate glazes just underneath the over-paint at risk," said Wicks. "Second, the veils were applied by an important late Baroque artist and are now part of the painting’s history.”

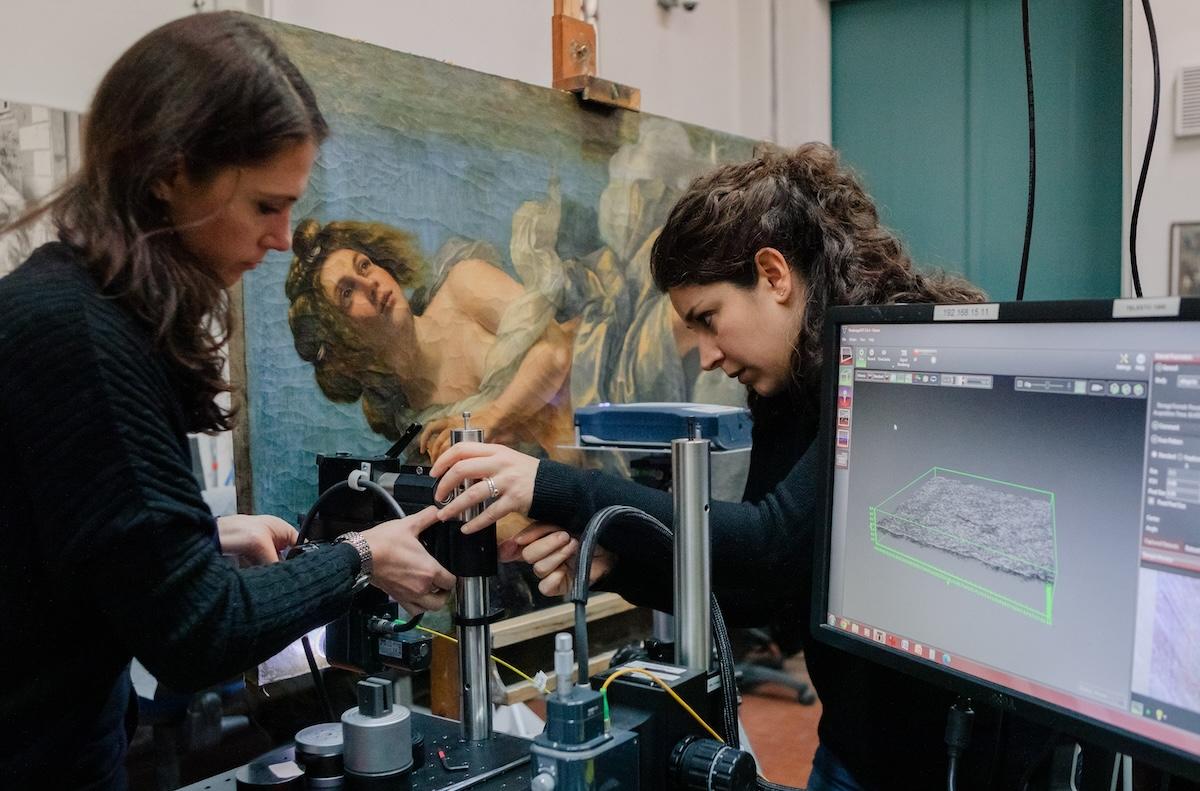

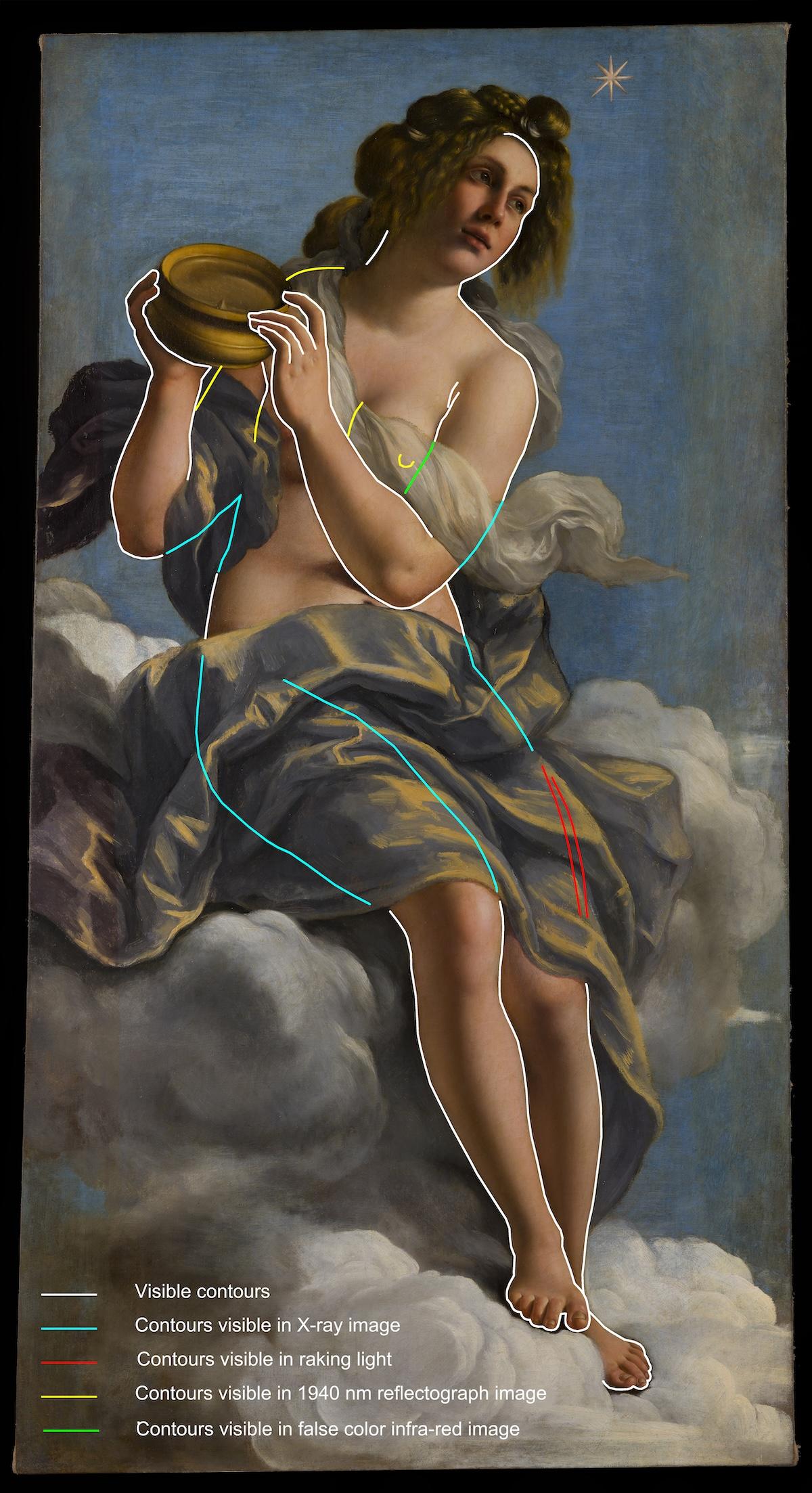

To map out what Artemisia did versus what Il Volterrano did, the scientists and conservators probed the painting at 16 depths, nanometer by nanometer. They used a tool called a reflectograph to see the places in which Artemisia changed around, and they used an X-ray to see through the white lead pigment that covered the figure’s thighs. From there, they were able to sketch out an accurate representation of Artemisia’s original composition.

The scientists were able to find some exciting changes that Artemisia made, as well as learn more about her technique. They found that Artemisia used very little lapis lazuli pigment, which at the time was more costly than gold. They also found a fingerprint that dated back to the painting’s creation. Wicks concluded that “the fingerprint was made when the original paint was wet, and it is highly likely that of Artemisia herself.”

This exhibition brings the original painting down from the ceiling to eye-level, so visitors will have the first opportunity to see her work up close. In addition, the show will highlight Artemisia’s career and influence, alongside the other masterpieces in the Casa Buonarroti.