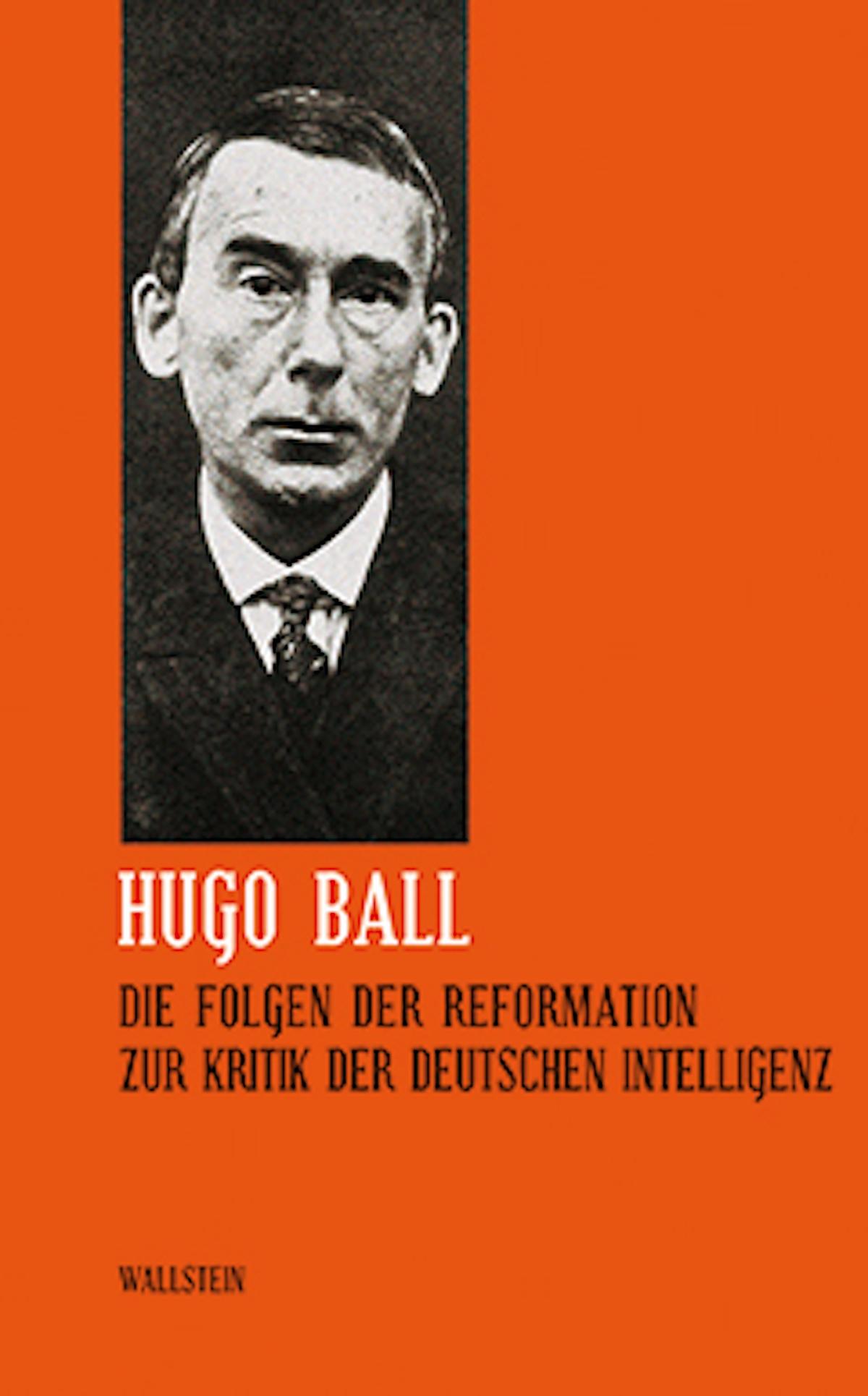

Hugo Ball (1886-1927) was a founder and critical theorist of the Dada movement in Zurich. He opened the Cabaret Voltaire, the mythologized birthplace of Dada in February 1916 while living in Swiss exile during the First World War. Only six months later, Ball renounced the emerging movement for believing it to be an art form for the “worst kind of bourgeoise.” His fellow Dadaist, Tristan Tzara persuaded him back, but in May 1917 Ball broke definitively with the movement after only being involved in Dadaism for two years. Ball’s relationship to Dadaism during his lifetime was short-lived, but it plays a significant role in the history of the movement to scholars today.

After his break from Dadaism, Ball worked for a short time as a journalist for the Swiss publication, Die Freie Zeitung. In 1919, he met German political philosopher, Professor Carl Schmitt. Schmitt would later become a key legal adviser to the Nazis. At the time of their short but powerful friendship, Schmitt and Ball worked together on a number of texts, including his controversial publication On the Critique of the German Intelligensia. In a 1923 letter to his wife Emmy Hennings, Ball says that Schmitt was “more important for Germany than the entirety of the Rhineland,” and a “great triumph for the German language and for legality.”