Wanderer is Smith’s first institutional solo exhibition in the UK in 20 years. With its medieval heritage and legacy of fantastical storytellers like C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Lewis Carroll, the city of Oxford is a fitting backdrop for Smith’s history-jumping, mystical cosmology. Described as ‘virtually self-taught,’ the artist was nonetheless raised in the rich artistic and intellectual world of her parents, the opera singer Jane Lawrence and the architect and artist Tony Smith.

In 1976, she moved from New Jersey to New York City’s Lower East Side, where her work was shaped by the AIDS crisis and feminist activism. After the social and political upheavals of the 70s and 80s, Smith began incorporating legends, religion, and history into her work. Wanderer encompasses works from this phase onwards.

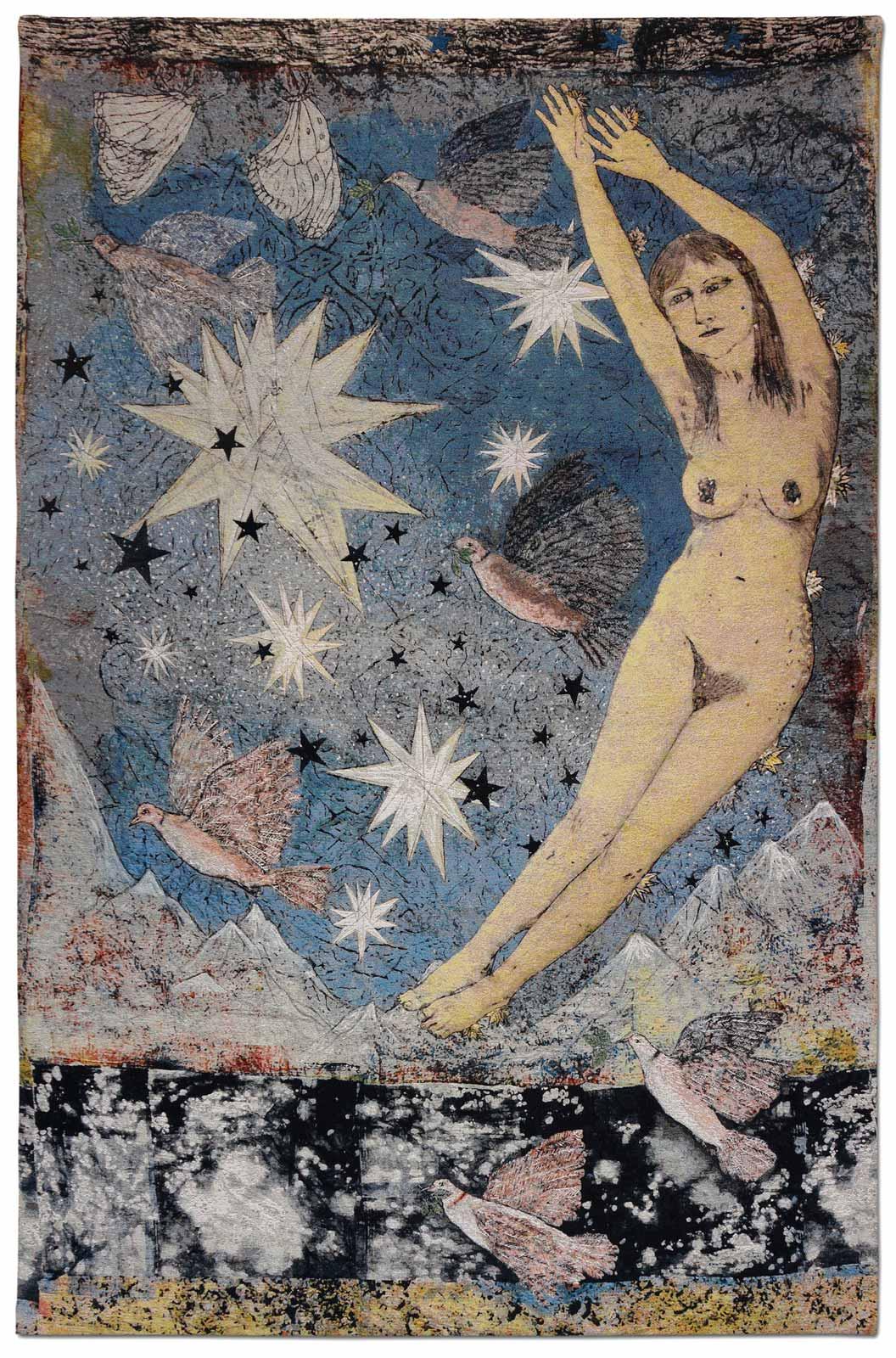

For Smith, printmaking represents a collective, universal experience. “Prints mimic what we are as humans,” she says. “We are all the same and yet everyone is different.” Since Smith began printmaking around 1980, she has partnered with master printers and workshops to explore a variety of scales and techniques. Some prints recall anatomical or botanical studies, while others arise from personal or literary sources.

Smith’s body-sized, hand-painted Pool of Tears II (2000) is inspired by Carroll’s drawings from Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (1886). Like many of Smith’s works, the message is as magical as it is menacing: although the print’s creatures pursue Alice with their scratchy claws and pointy beaks, their glowing eyes stare only at the viewer, as if we too are part of the chase.