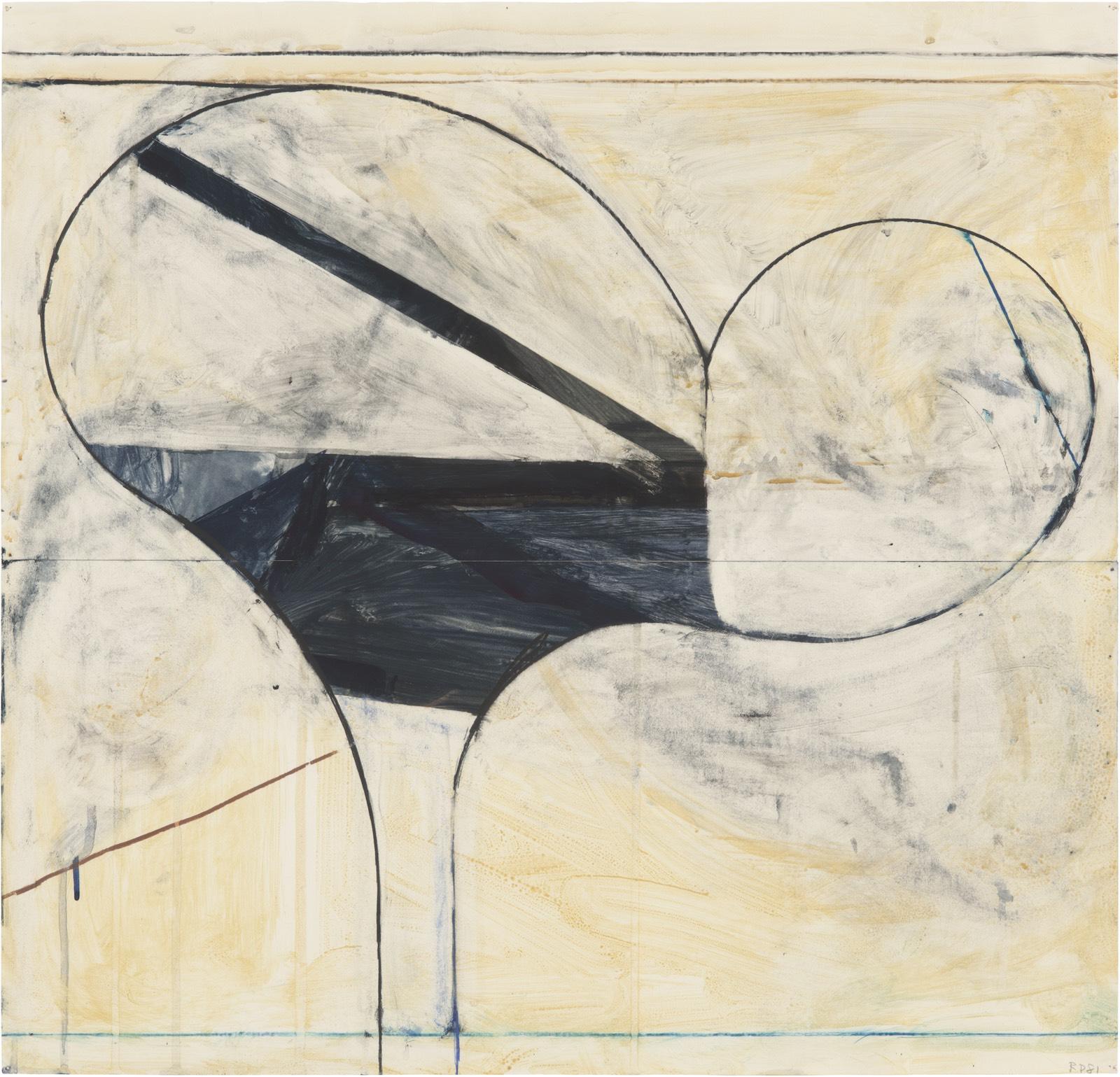

While Diebenkorn is best known for his signature Ocean Park paintings—watery pale blue skies at play with horizontal geometric patterning that suggest landscapes in the sky—he is also noted for his more conventional figures and work that lives in the mode of the Bay Area Figurative painters, including David Park, Elmer Bischoff, and Wayne Thiebaud.

But this particular still life is a declarative work, unlike most of Diebenkorn’s other figurative pictures. In its flatness, Studio Floor—Camelia is reminiscent of Japanese prints and drawings—and of mapping. Diebenkorn, who worked as a cartographer in 1945 alongside Walt Disney animators, would fly over miles of flattened landscapes.

“One thing [that] I know has influenced me a lot,” Diebenkorn was often quoted as saying, "is looking at [the] landscape from the air. ... Of course, the earth's skin itself had 'presence'—I mean it was all like a flat design—and everything was usually in the form of an irregular grid."