The issue of gender in archaeology as a scholarly, theoretical question gained prominence in the 1980s during the so-called post-processual movement, but it truly owes its origins to the wave of feminist archaeology that came before in the 1960s and 1970s. Scholars of feminist archaeology called for a more equitable approach to constructing archaeological narratives, one in which women were active participants in the creation of human culture and history and not simply “added and stirred” into the history pot for the sake of having them there.

The approaches of this movement were very much informed by the flows of second-wave feminism which challenged a universal and timeless dominance of the male sex and, although critical to starting a movement, in many respects it still operated on a gender binary of men versus women. Later approaches developed in the 80s opened the conversation up further by expanding beyond a male-female/man-woman binary of gender, and work in the 90s and early 2000s progressed even further, riding the inertia of third-wave feminism which purports a fluidity of identity and embodied, lived experiences.

Much of this theoretical grappling has resulted in works that speak more about sliding scales of masculinity and femininity on which individuals can variably occupy space regardless of biological sex and more dependent upon their contextually derived positions within their respective time periods, cultures, and lived realities. Though this is by no means a perfect system and does not come close to covering the full spectrum of human possibility (for instance, the idea of a distinct third gender exists in many cultures such as ‘Hijras’ in Hinduism and those referred to as ‘two-spirit’ individuals in certain Native American tribes), such interpretive tools allow us to parse out gendered identities that give room for emic (within a group) voices rather than relying solely on etic (outside a group) biases, most typically based on Western binaries and modern scholarly prejudices.

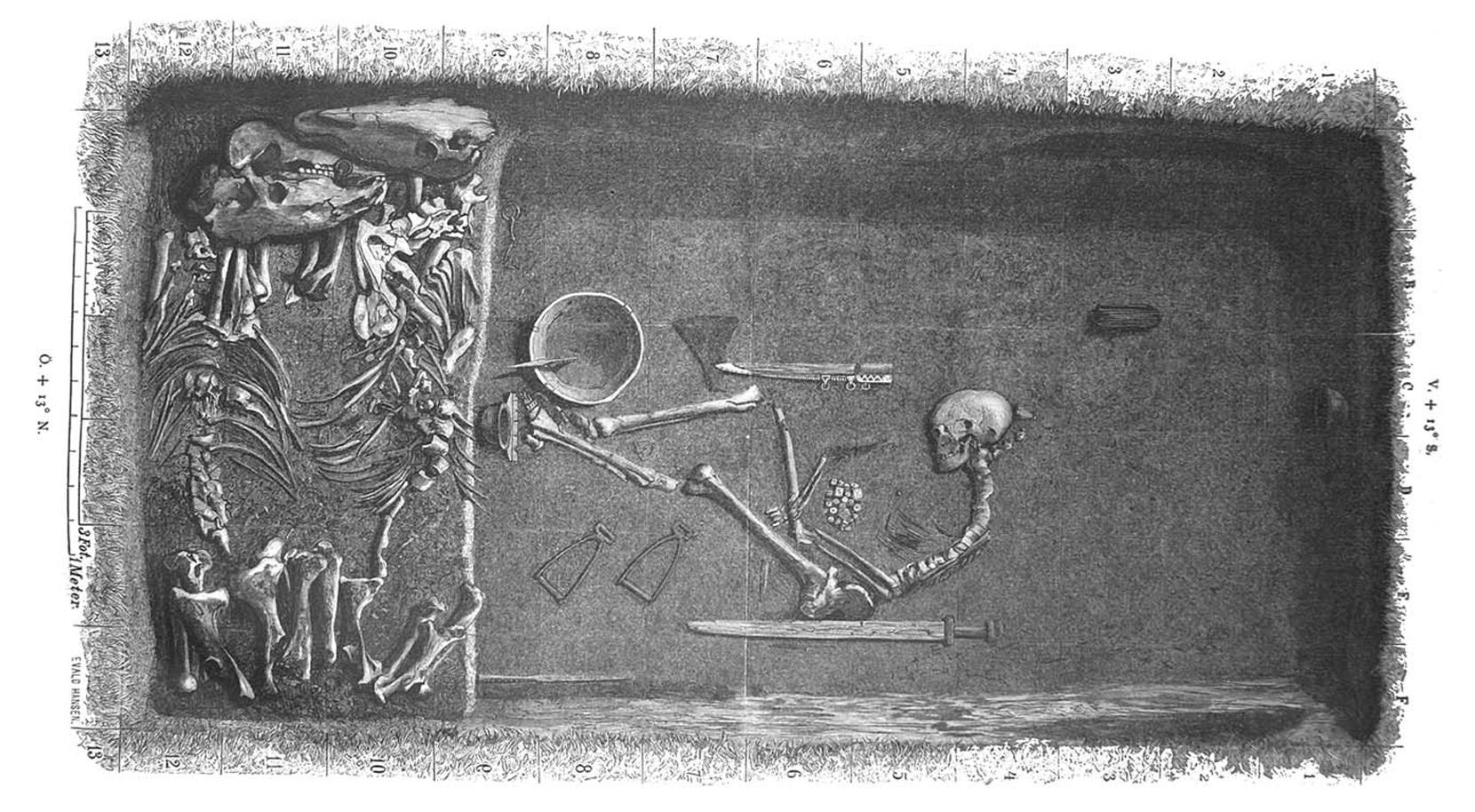

In recent years, work on Viking-era finds in Sweden and other Scandinavian countries has exemplified how we treat gender in the archaeological record, particularly in grave contexts. Researchers from Stockholm and Uppsala Universities revisited a prominent Viking burial from a Swedish town called Birka, originally excavated in 1889. The burial, Bj 581, dates to between the 8th and 10th centuries CE and is notable as one of the best furnished and preserved graves of a Viking warrior to date. Within the grave were a sword, axe, spear, armor-piercing arrows, a battle knife, two shields, two horses, as well as a full set of gaming pieces which are typically taken as a sign of one’s knowledge of tactics and strategy. The original excavators looked to the grave goods, all materials indicative of a warrior identity, and, without examining the skeleton, concluded that the interred individual was a biological male, and thus a man in gender. Now, it has been and is still not uncommon to also find biological females in Viking-era burials with weapons, but the richness of this particular grave was evidence to excavators and other scholars later in the 1940s that this individual was a warrior of extremely high status and thus naturally had to be male.