She studied under Hans Hoffman at the Art Students League and her work was admired by the influential art critic Clement Greenberg who visited her studio in the nascent days of Abstract Expressionism. Unfortunately, like so many other talented female artists before and since, as the fame and fortune of her male contemporaries grew, she faded into obscurity.

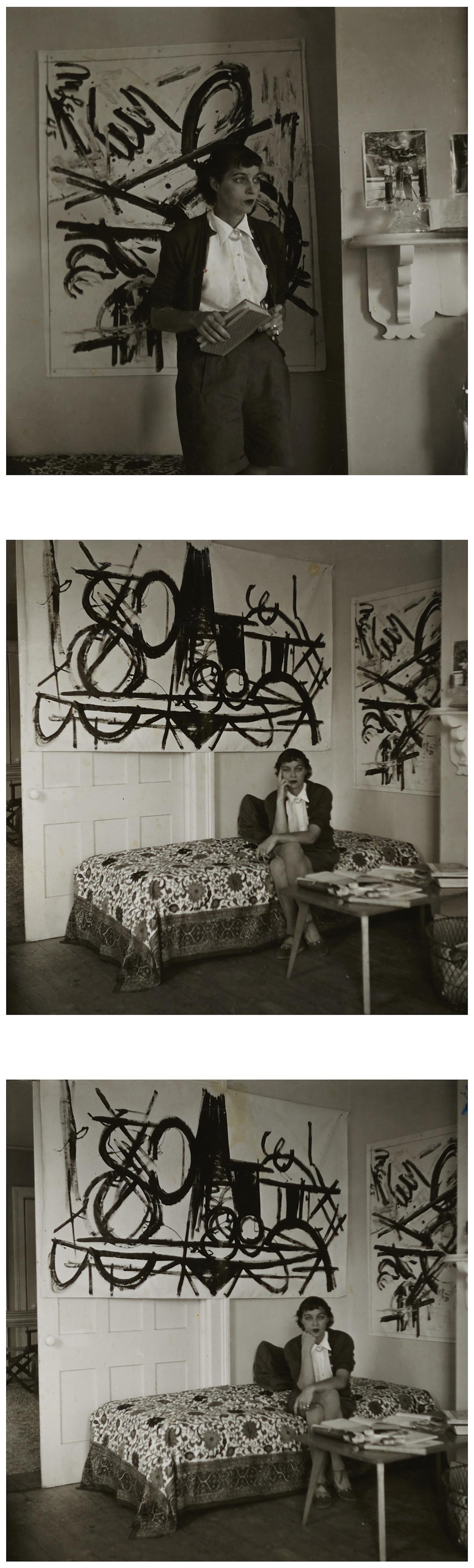

Detail of Michael West in her studio with Black and White (1947), 1947.

The abstract expressionist painter and Chicago-born poet Corinne Michelle West (1908-1991) was thirty-one years old when she officially changed her name in both her personal and professional life to Michael. The year was 1939 and in the testosterone-driven milieu of the New York avant-garde, Michael West was being noticed.

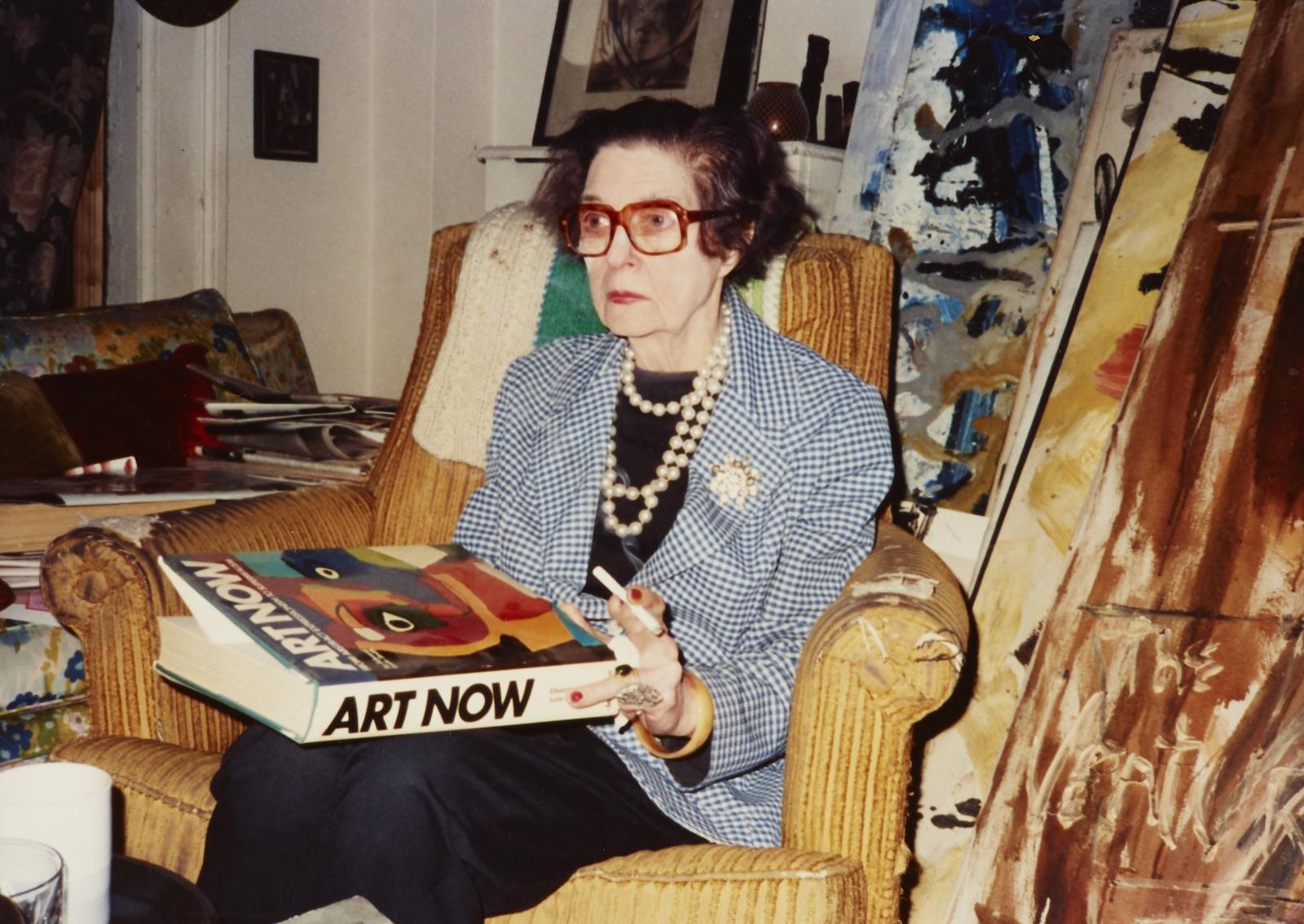

Michael West in her apartment, circa 1977.

Michael West in her summer rental, Stonington, Connecticut, 1955.

The current exhibition, Epilogue: Michael West’s Monochrome Climax, her second solo show since 2019 at Hollis Taggart in New York, seeks to correct the historical record. This well-documented show reveals the dynamic forces that influenced West’s volatile series of largely black and white paintings from the late 1940s through the early 1980s and we marvel at why she is not better known today.

Following the groundwork laid by Taggart in the previous show of West’s paintings, essays, and poems, Space Poetry: The Action Painting of Michael West, this exhibition focuses on West’s fascination with the yin and yang modalities that a limited palette of primarily black and white suggests.

Art does not occur in a vacuum and although West developed a very personal iconography of mark-making she acknowledged her debt in Notes on Art to those artists whose work left lasting impressions on her way of thinking about art. Early on in her evolution she embraced cubism, particularly the work of Spanish painter Juan Gris (1887-1927). Later, in 1935, her “transcendent experience” with Arshile Gorky’s (1904-1948) ink on paper series, Nighttime, Enigma, and Nostalgia led to an intense and transformative relationship with the Armenian-American artist.

West saw Gorky’s genius as “the real influence in my life,” but she declined his entreaties and, rather than marry him, she protected her independence by choosing to go a separate way. This decision, while an indication of her tenacity, may have contributed to her virtual erasure from the record books. In comparison, West’s colleague and fellow painter Lee Krasner (1908-1984) married Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). Following Pollock’s death in a car crash in 1956, Krasner’s work eventually moved into the spotlight and she holds a prominent place within Abstract Expressionism today.

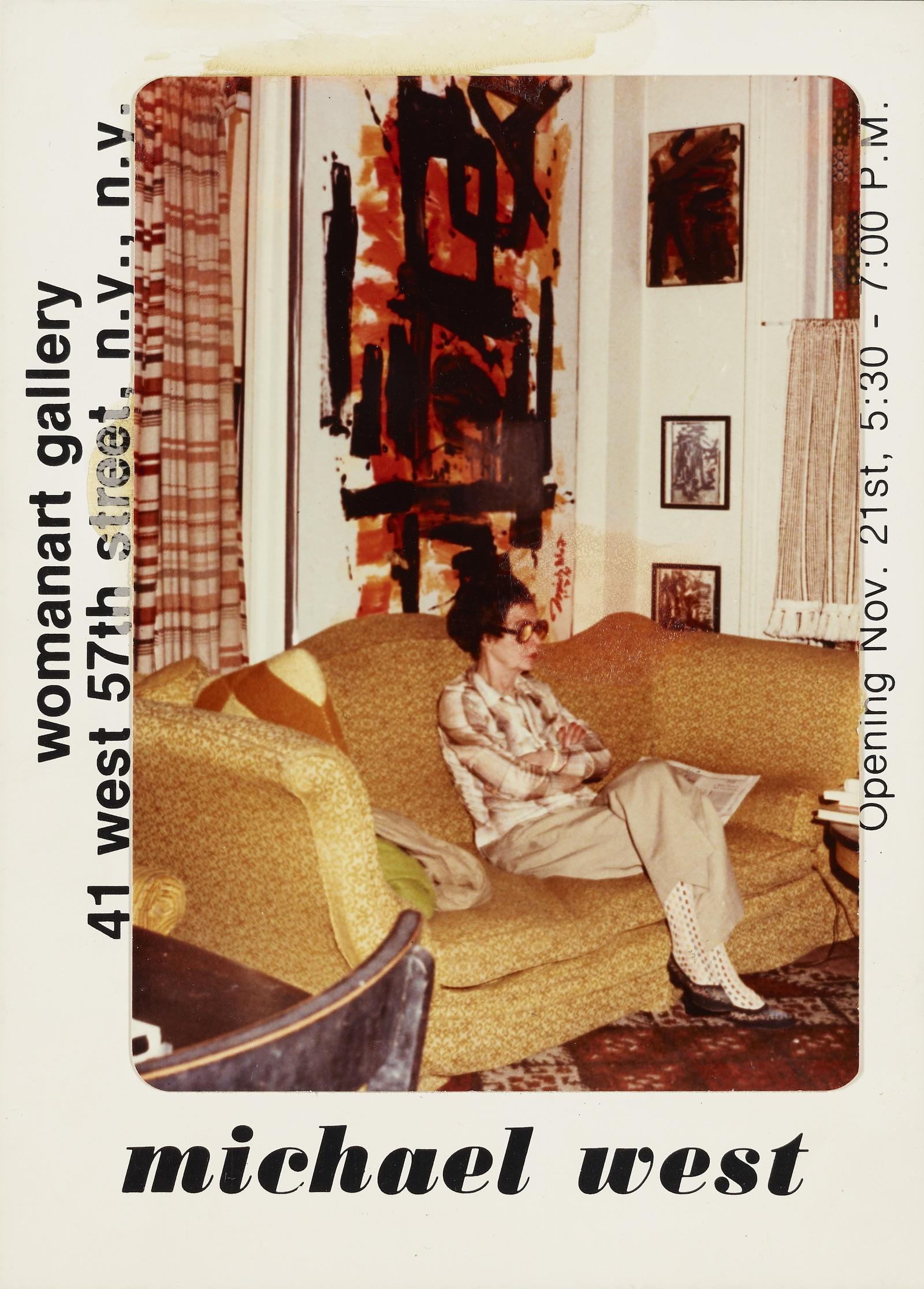

Catalogue cover image.

West also shares an affinity with another eminent abstract expressionist, Richard Pousette-Dart (1916-1992), but it was Pollock who she admitted, “Came on the scene like a meteor—[h]ere everything was solved for me once and for all. He was the most immediate, violent, heroic, painterly and non-painterly—that anyone could be.” However, admiration does not imply mimicry. West’s swirling curlicues of paint in Mystic Energy from 1946 reverberate with Pollock’s work from the early 1940s yet she maintained her own brand of “lyric cubism” throughout that period.

In the early 1960s West occasionally took up the practice of working on a painting while it was stretched out on the floor, a method pioneered by Pollock.

In her much later, totemic, vertical Generations from 1974, thick, black, Japanese-like characters are stacked, floating against a cloud of fiery gold and orange pigment recalling Hans Hoffman whose instruction she rejected after six months of study, saying his classes were like participating in a “cult.”

West’s abnegation of color was reinforced by the graphic, exclusively black and white paintings of Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Pierre Soulages, a practitioner of Tachisme, the French version of Abstract Expressionism. Exhibitions titled Black & White, and variations of the theme started popping-up in museums and galleries in New York in the 1960s. West’s writings about the power of binary contrasts are mirrored in the vitality of her paintings throughout her career.

Michael West invitation for Womanart Gallery solo show, November 1978.

In a detailed, informative catalog essay that accompanies the exhibition, distinguished curator and art historian Dr. Ellen Landau unravels the trajectory of West’s artistic development. West recorded her thoughts and reflections on creativity in her poetry and copious writing, a rich archive of material that informs her visual expression. In at least one instance, West described her life-long artistic goal was to craft a poem in paint. In 1996, five years after her death, the Pollock-Krasner House Foundation recognized her achievement by presenting a retrospective entitled Michael West: Painter-Poet.