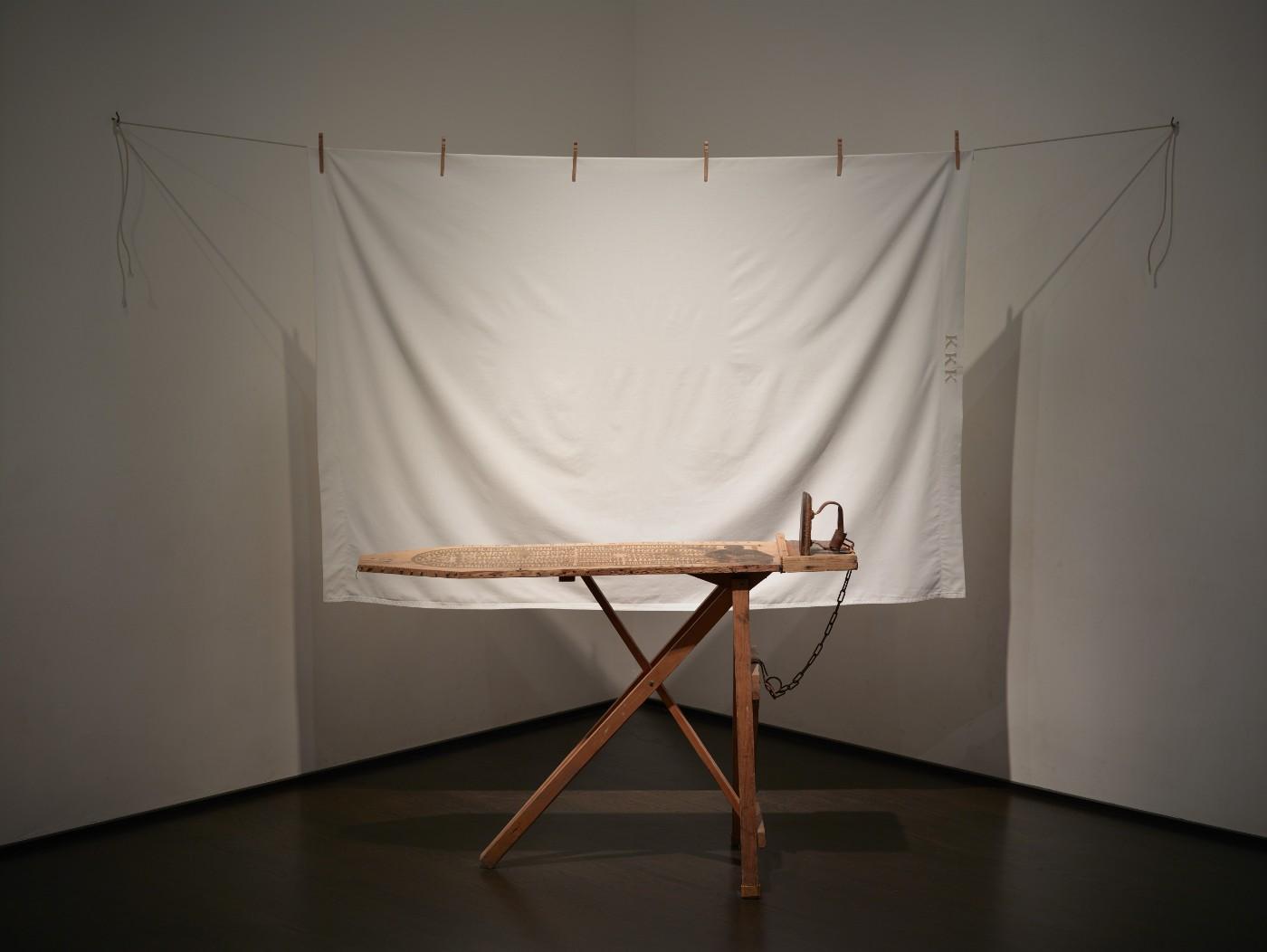

Emanating from a screen near the entrance, Saar’s voice permeates the gallery, explaining her process of creating I'll Bend But I Will Not Break, an installation positioned in the corner. The work’s ironing board, she says, “reminded me of the shape of a slave ship.” As such, she imprinted its surface with an image of the gruesome efficiency of space practiced aboard the late 18th Century British slave ship Brooks. What at first are unrecognizable in their cramped proximity on closer inspection become black bodies chained to and wedged against one another so tightly that the conditions violated even the era’s already genocidal laws governing the slave trade. Their transatlantic voyage is both unimaginable and impossible not to imagine.

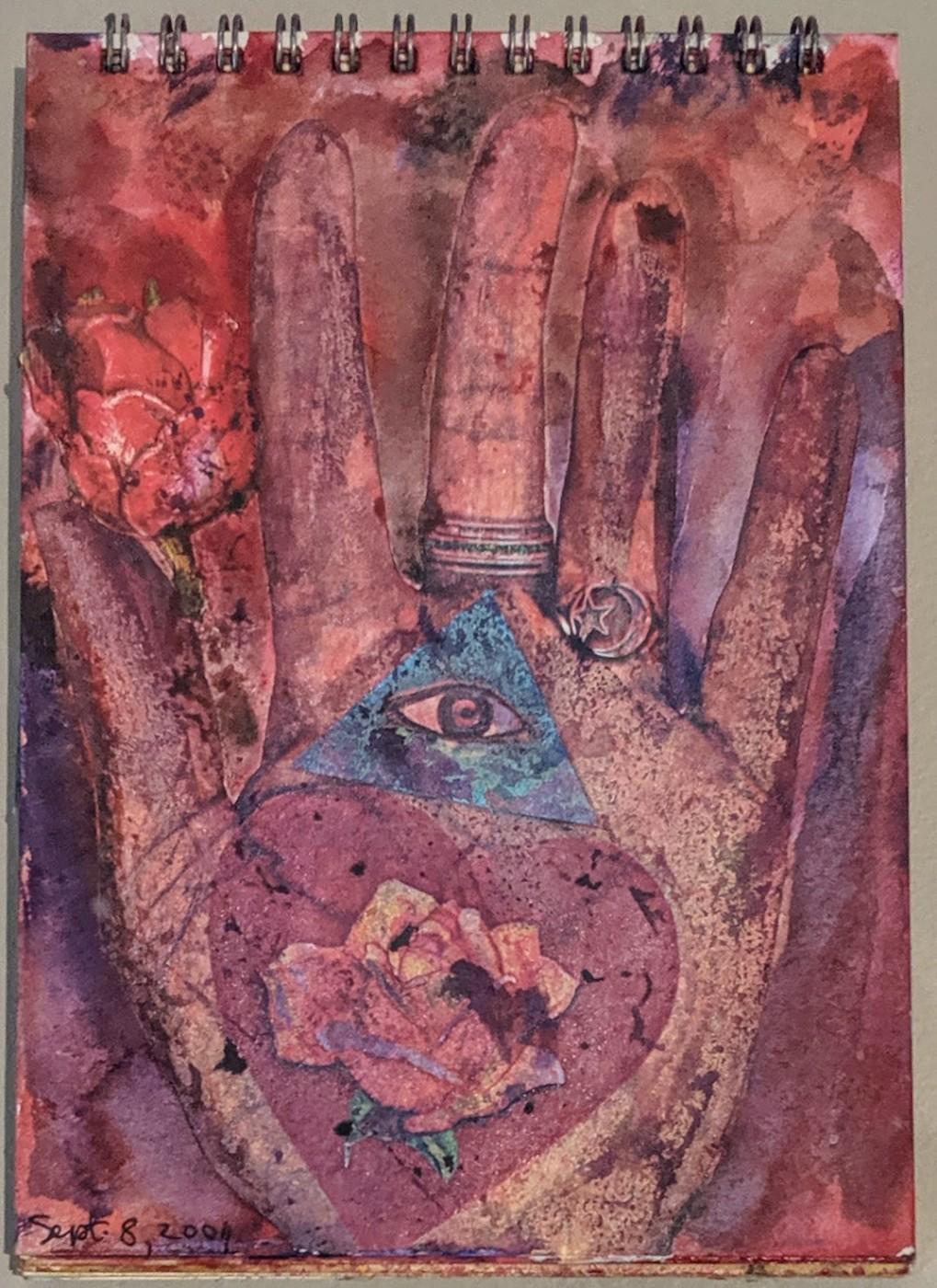

Betye Saar, Page from Aix-en-Provence, France / Los Angeles sketchbook, September 8, 2004, collage and watercolor on paper.

In 1967, Betye Saar started remaking the world.

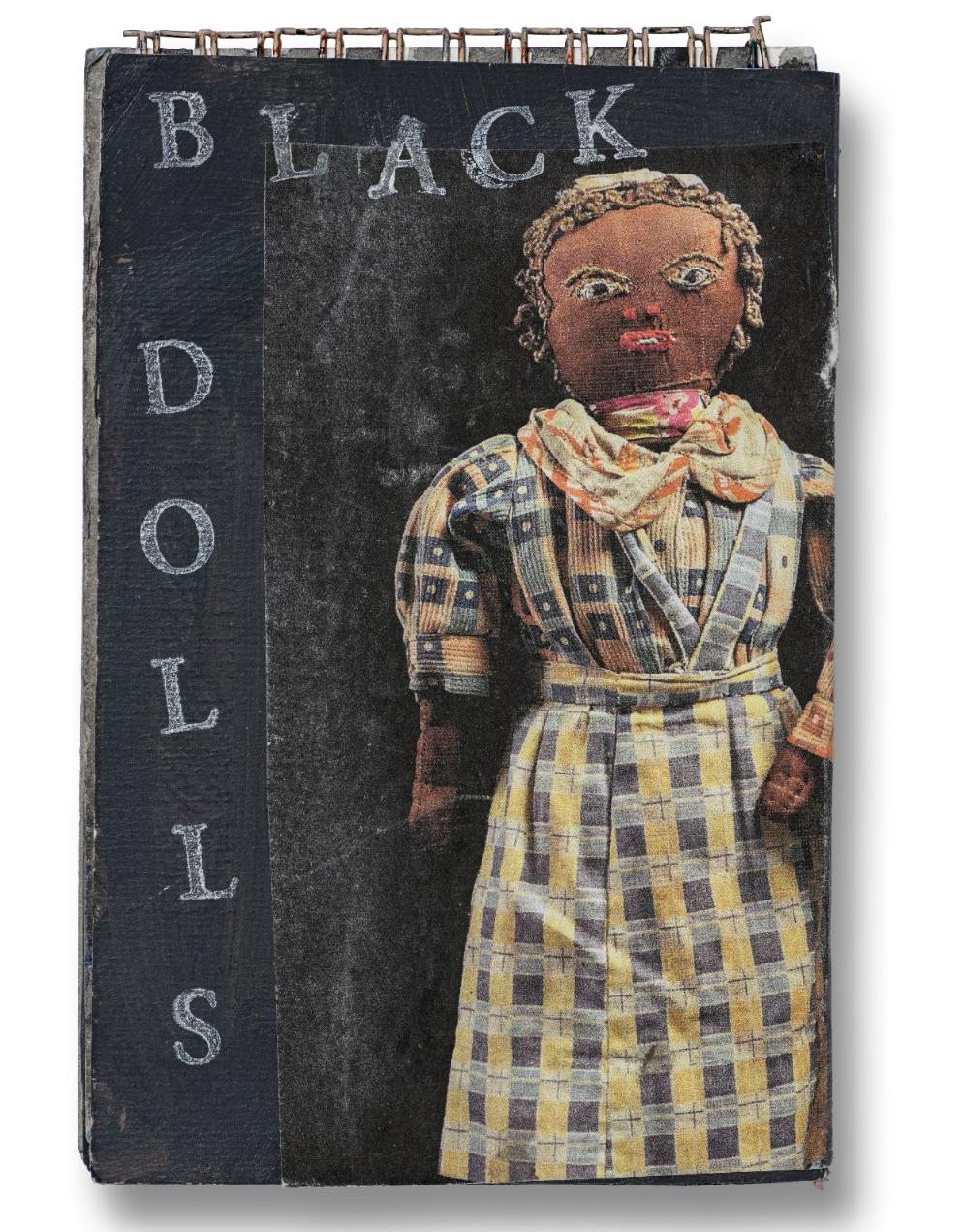

She began by collecting society’s flotsam and jetsam abandoned to second hand stores and parking lot flea markets where a blue bottle or an Aunt Jemima figurine might go for a dollar or maybe a quarter. Back in her studio, she transformed them into assemblages that function as a combination of windows and earthmovers, able to illuminate and excavate truths long buried beneath America’s centuries old substrata of racism and misogyny.

Call and Response, Saar’s current exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), is a small but poignant portrait of the world Saar created over the course of her half century career.

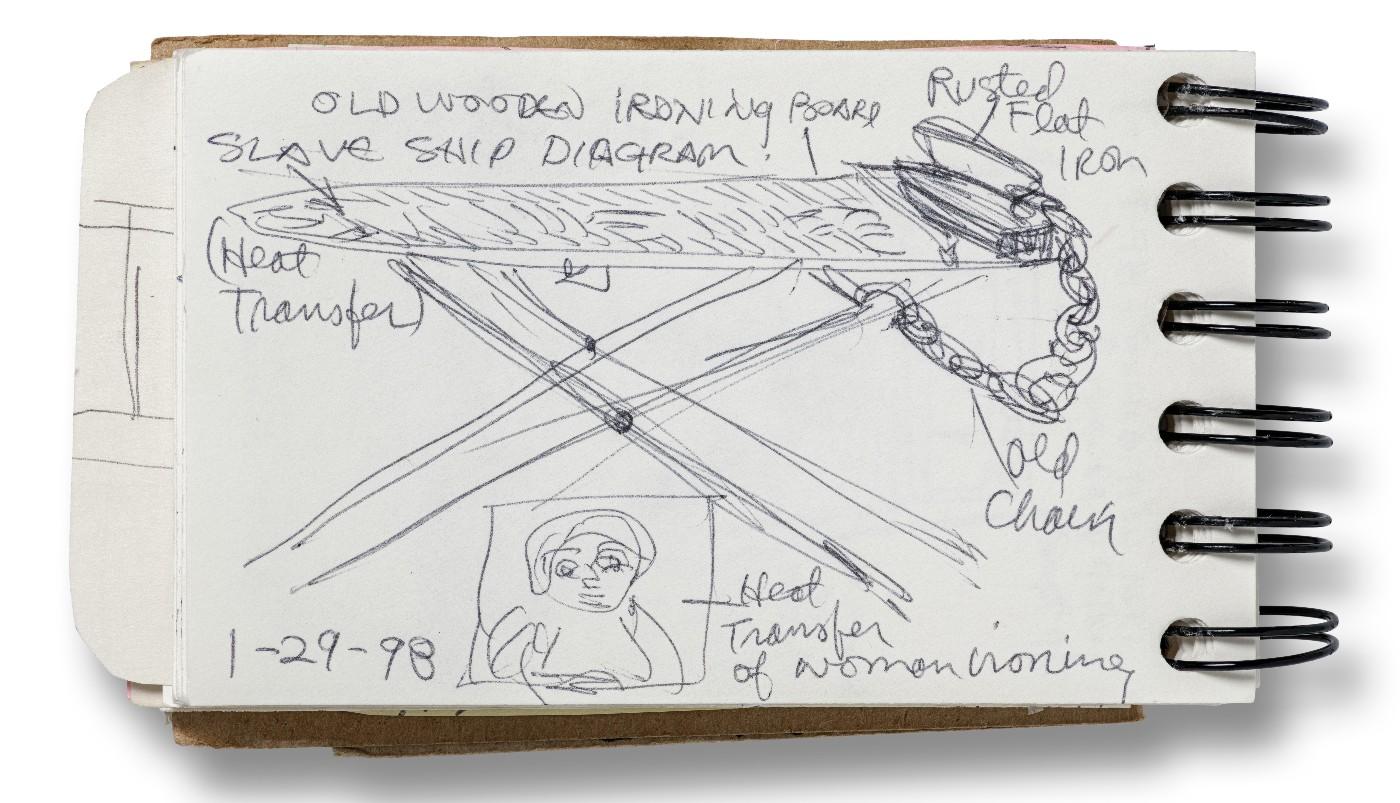

Betye Saar, Page from 1998 sketchbook, January 29, 1998, ballpoint pen on paper, collection of Betye Saar, courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, © Betye Saar.

Betye Saar, I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break, 1998, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2018 Collectors Committee, © Betye Saar.

An iron is poised ominously at the board’s right edge, threatening to flatten the figures further still. Behind it hangs a crisply pressed white sheet monogrammed in white thread with the letters “KKK.” The brutal history of domestic labor demanded of enslaved African women and their daughters becomes palpable along with the often state sanctioned violence that accompanied even the slightest defiance. As with many of her pieces, the work communicates with the force of an incoming tide.

Betye Saar, Supreme Quality (detail), 1998, the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Mortimer and Sara Hays Acquisition Fund, © Betye Saar.

Adjacent is Supreme Quality, one of Saar’s quintessential assemblages that incorporates the familiar figure of Aunt Jemima who is fixed on a washboard anchored in a laundry tub. Unlike the passive character of syrup labels, this Jemima’s upward turned eyes seem to be joyously pondering what to do with the two guns cradled beneath the crooks of her elbows. Beneath her are the words “Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroines.” Unapologetic in its militarism, the work is also resolute in its analysis of the historical conditions that created its necessity.

But Call and Response is not exclusively, nor perhaps primarily about the past, as deserving as it is of our long overdue attention. Instead the exhibition functions as a kind of time machine to a possible future, powered, as it were, by the mysticism imbued in many of Saar’s works.

Betye Saar, Sanctuary Awaits, 1996.

Sanctuary Awaits is one such work, taking the form of a chair, or perhaps a throne, fashioned from the wood of gnarled trees and crowned with a halo of amber colored bottles. More than just a sculptural piece, the work is connected to a spiritual practice dating back to the Kingdom of the Kongo that was transported to the Americans and Caribbean by those pressed into slavery. In Creole culture, it was believed that bottles fastened to the branches of trees were able to capture evil spirits who were destroyed by sunlight concentrated beneath the glass. In this deeply rooted mytho-historical context, Saar’s sculpture becomes a machine built with ancient technologies passed down through the generations and capable of protecting its user from harm.

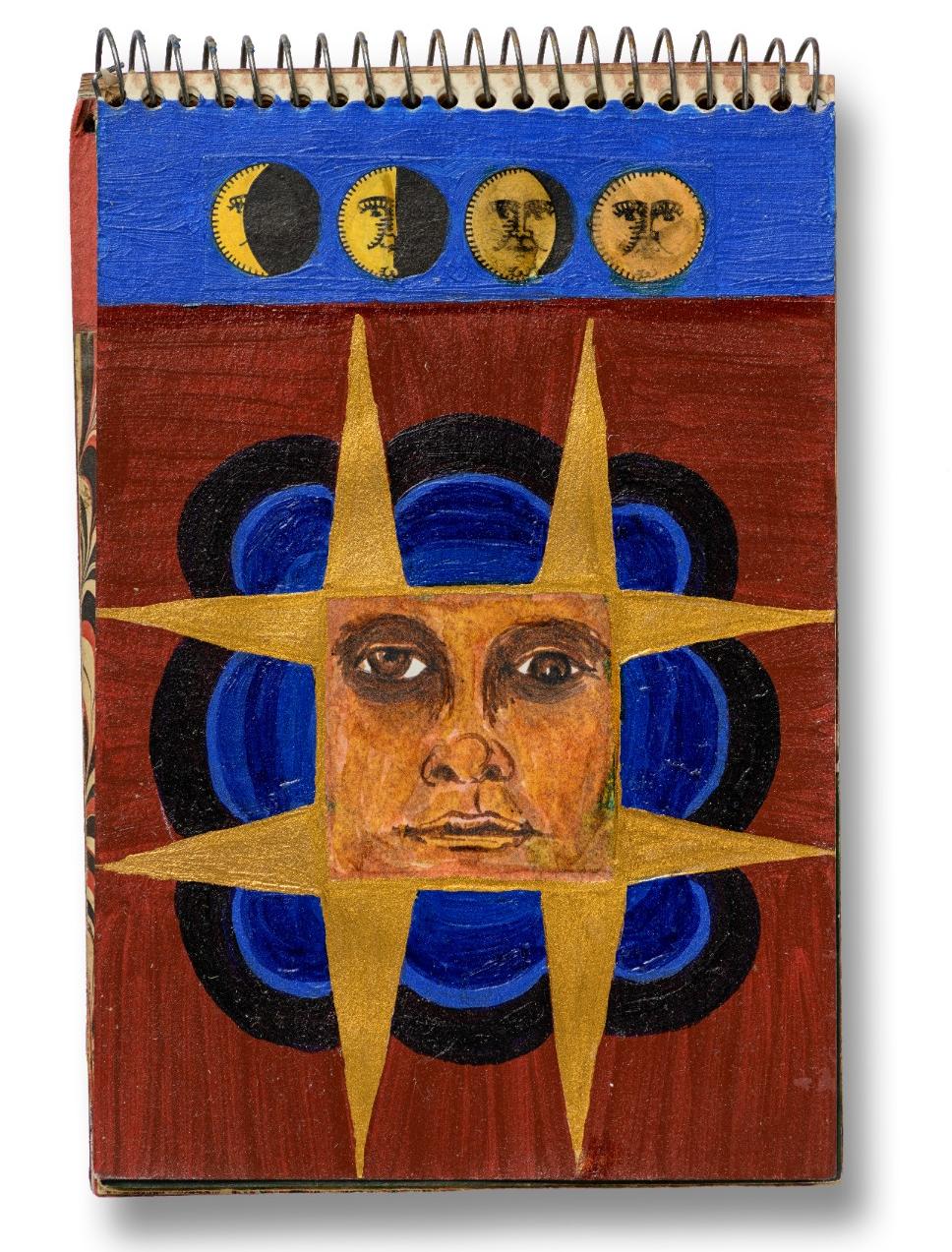

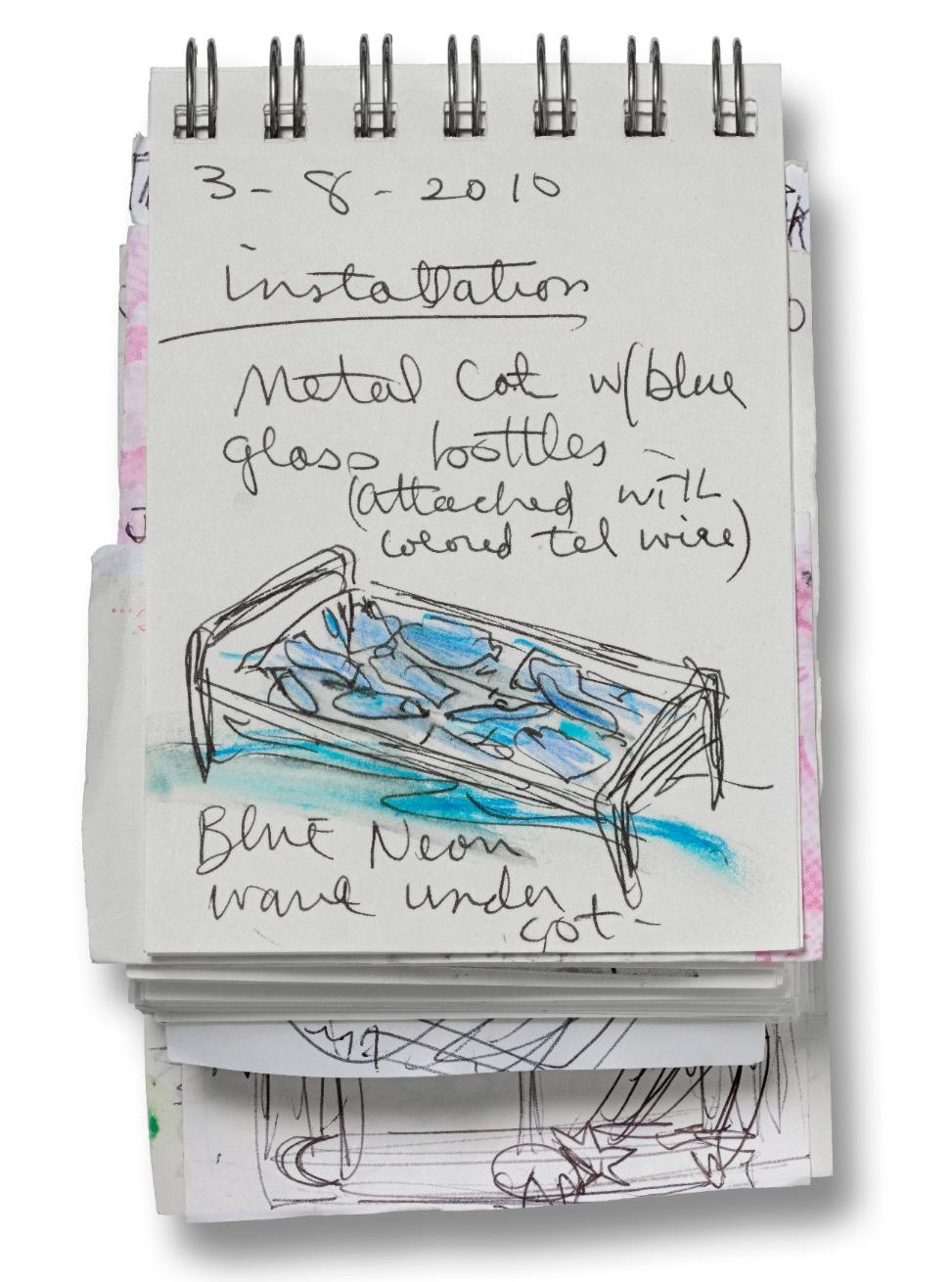

Her mysticism is also present within several of the never before exhibited sketchbooks, particularly those occupying the center of the gallery’s three vitrines. As exhibition curator Carol S. Eliel commented in a recent interview these are, “what I call her travel sketchbooks, which contain more finished watercolors, gouaches, and collages than what I call her working sketchbooks, which have the ballpoint and marker sketches (which are in the outer two vitrines). While the travel sketchbooks don't correlate specifically to individual works, they are full of recurring motifs in her work—the heart, the palm of the hand, eyes, the flaming cross, etc. She’sinterested in astrology and is a Leo, so the lion also recurs in her work as a motif.”

One page, dated 7-24-74, for instance, depicts lozenge motifs that Saar saw on a grave monument in Jacmel, Haiti. These patterns, which date back to the Neolithic era and often represent fertility, are combined with symbols of a star and the moon, the human heart, and a cross with flames emanating from its horizontal beam. Several others depict a heart embedded in a palm, an image that appears throughout her oeuvre and finds its origins in various spiritual sects particular to the Northeastern United States where it symbolizes charity and a loving welcome.

Betye Saar, The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts), 2014, the Eileen Harris Norton Collection, © Betye Saar.

It is tempting to read into these works a new age spirituality devoid of radicality and suffuse with a kind of “give peace a chance” mentality. But to do so would be to ignore that the future Saar’s work projects is possible precisely because of her unflinching look at the past and honest appraisal of the present. This future is also contingent on the extreme heroines that she so accurately identifies in Supreme Quality and certainly, Saar is one of them.

The only quality lacking in Call and Response is that there is not more of it. Containing about 40 objects, it is more of a survey than the retrospective viewers might long for. But as Eliel commented, it was Saar who chose to limit the size of the exhibition. “I asked her if she could do anything at LACMA in the way of an exhibition what would she do. I was prepared to do anything,” said Eliel, continuing, “At the time I asked her, she was 90 years old and she said she felt she didn't have that much time left and wanted to spend that time in her studio making new work.” The decision, said Eliel, “not to do a big show was really hers.”

While Saar’s reasons for setting these priorities are her own, the necessity of new work by her is all too clear within our current historical moment. Hopefully, this time it won’t take so long for it to receive the attention it deserves.