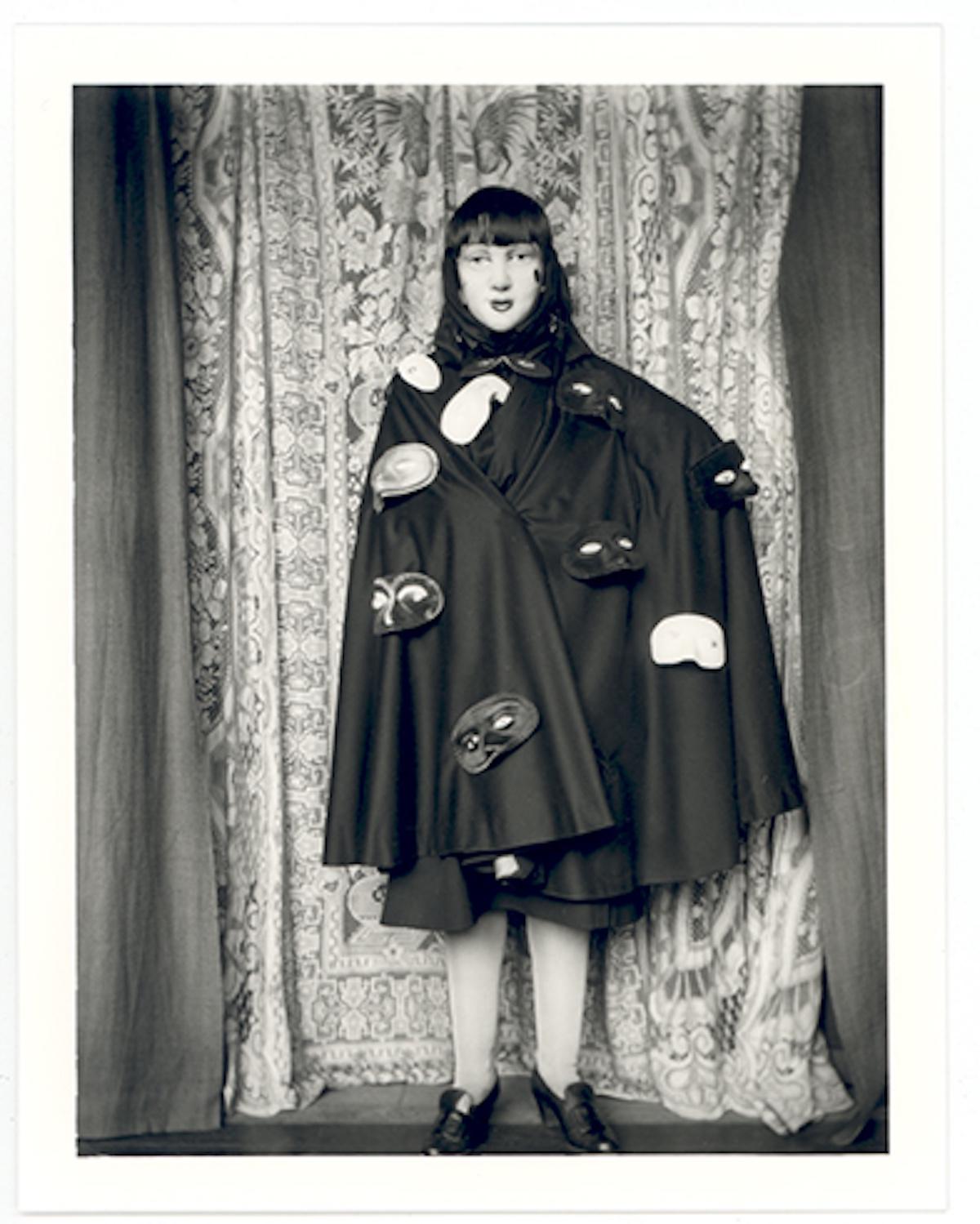

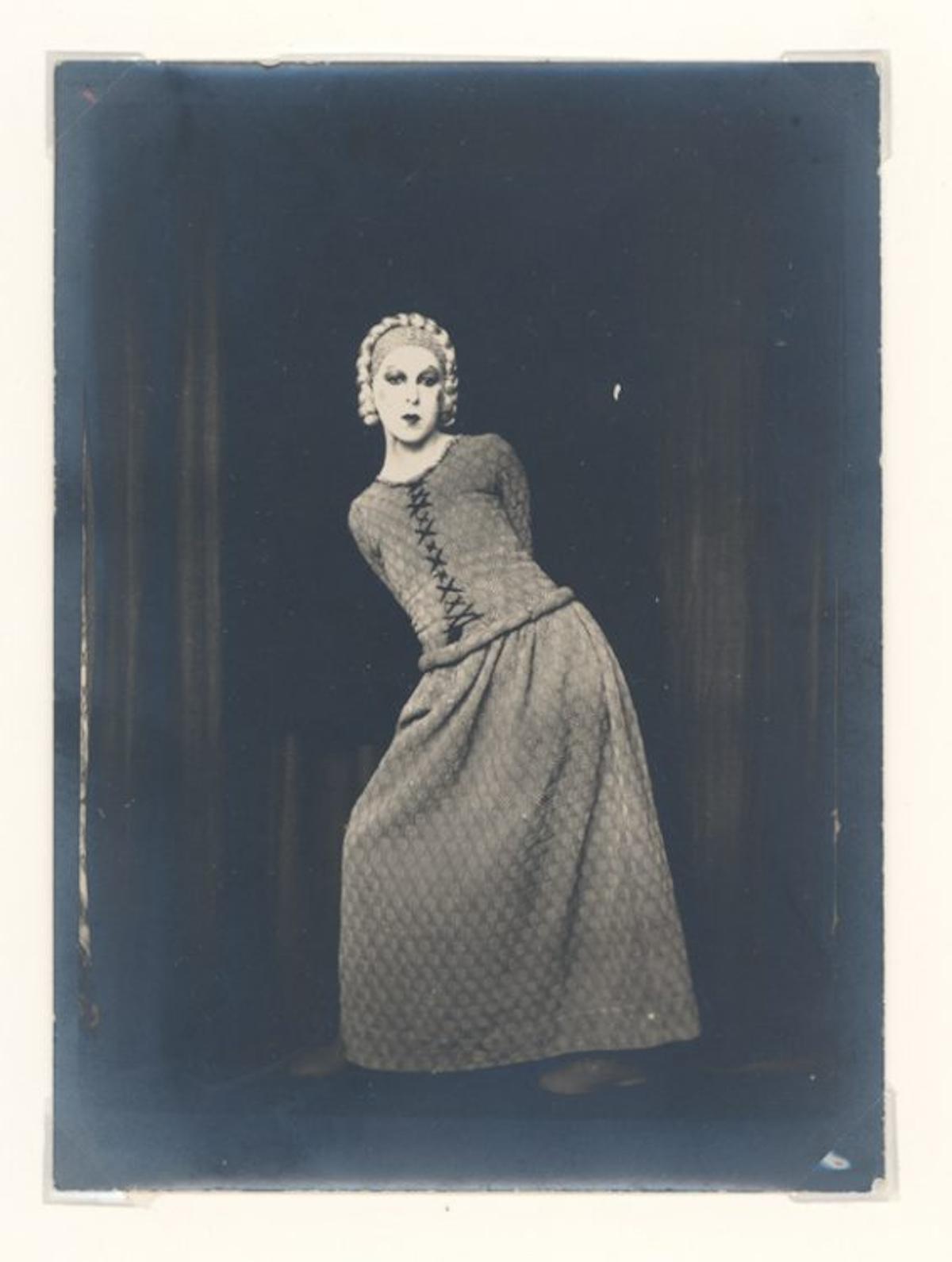

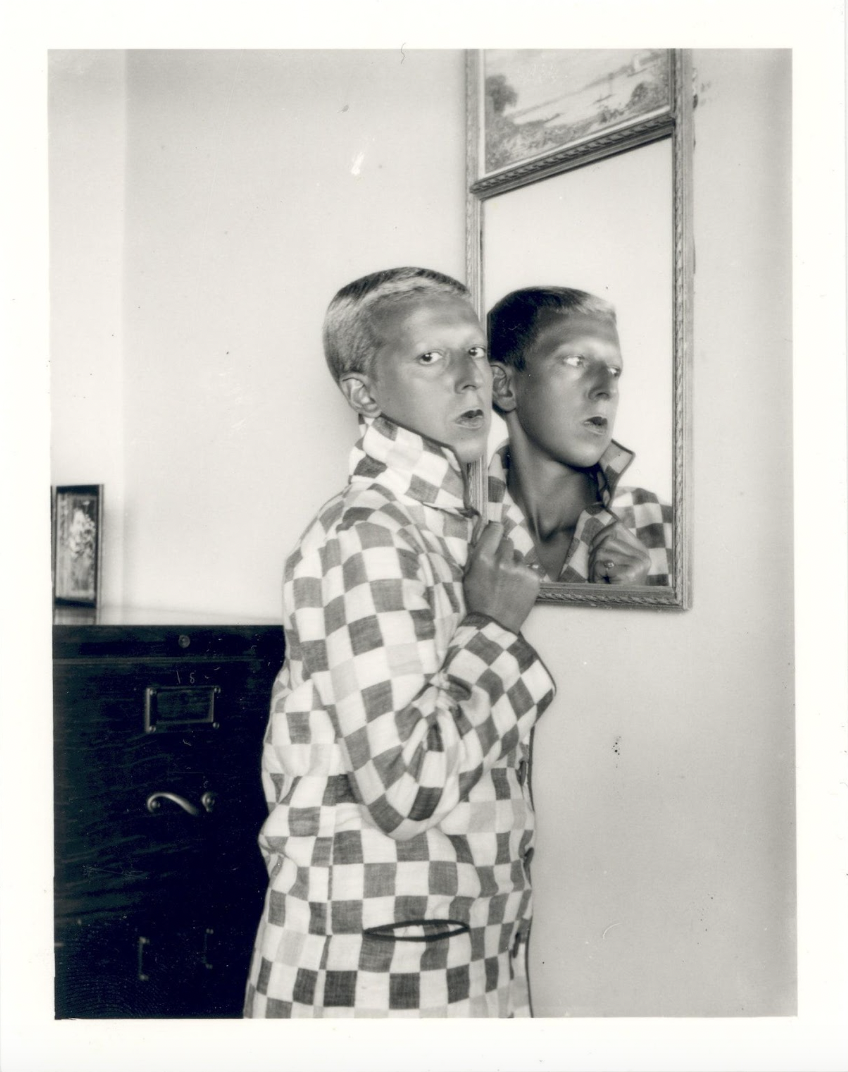

Jordan Reznick, an art historian who specializes in photography, settler colonialism, and transgender studies contends that the reason for this mislabeling of Cahun, and their life-and-art partner Marcel Moore (1892-1972), throughout art history is due to an attempt to use period-specific terminology and concepts related to gender. Transness, however, was not a part of the cultural zeitgeist of the 1920s and 1930s, which Reznick argues does a disservice to the true context of Cahun’s artistic catalogue, and contributes to the erasure of trans people throughout history. Therefore, it can be argued that part of Cahun’s artistic vision was to dismantle widely accepted theories and beliefs on what gender should look like.

In the same way that Cahun used their art to queer traditional notions of gender, they also used it as a force of resistance against the Nazi regime. Having moved from their home country of France for Jersey, one of a series of islands between the English and French coastlines, Cahun and Moore established a small but mighty movement of resistance against Nazi rule. The Nazi regime gained control of all islands in the English Channel during World War II, including Cahun and Moore’s home of Jersey. While the bigoted regime occupied the island, the pair distributed anti-Nazi propaganda across Jersey, as well as displayed anti-fascist slogans and artwork throughout the region.

Cahun and Moore even formed resistance groups and salons with artists and writers alike, André Breton being among a coalition formed in Paris in 1933. Scholar of Modern and Contemporary Art, Katherine Smith asserts that Cahun and Moore’s distribution and installations of anti-Nazi material and art served as a continuation of the anti-war narratives that are rooted throughout several Modernist movements. This radical demand for liberty and equality against the Nazi regime eventually led to their imprisonment in 1944, for which they were sentenced to death. Thankfully, Jersey was liberated from Nazi occupation in 1945 before this could happen.

Prior to their death in 1952, Cahun helped establish a movement among, and for, queer artists and Surrealists alike. It could be argued that contemporary photographers, such as Cindy Sherman, were inspired by Cahun’s chameleon-like artistic identity. Cahun’s wishes for a free and liberated world during the Second World War arguably stand today with a broader message of freedom, inclusion, and acceptance of not just queer artists, but of all LGBTQ people finding their way to authenticity, just as Cahun did through their explorative photographs.