As women’s lives were confined to the private sphere, biblical artwork of women became more consumed and celebrated within the home, since religion was a woman’s outlet to the public sphere. The prominence of artworks depicting the biblical figure Judith, among other icons like Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary, within the home strengthened the link between the public and political space, as well as the private domestic space. This allowed women to have a role model who transgressed the limitations of being confined to domesticity.

If women had control of their private lives and found inspiration in the strength and iconography of Judith as a transgressor of a private versus public divide, women would gain a stronger sense of identity.

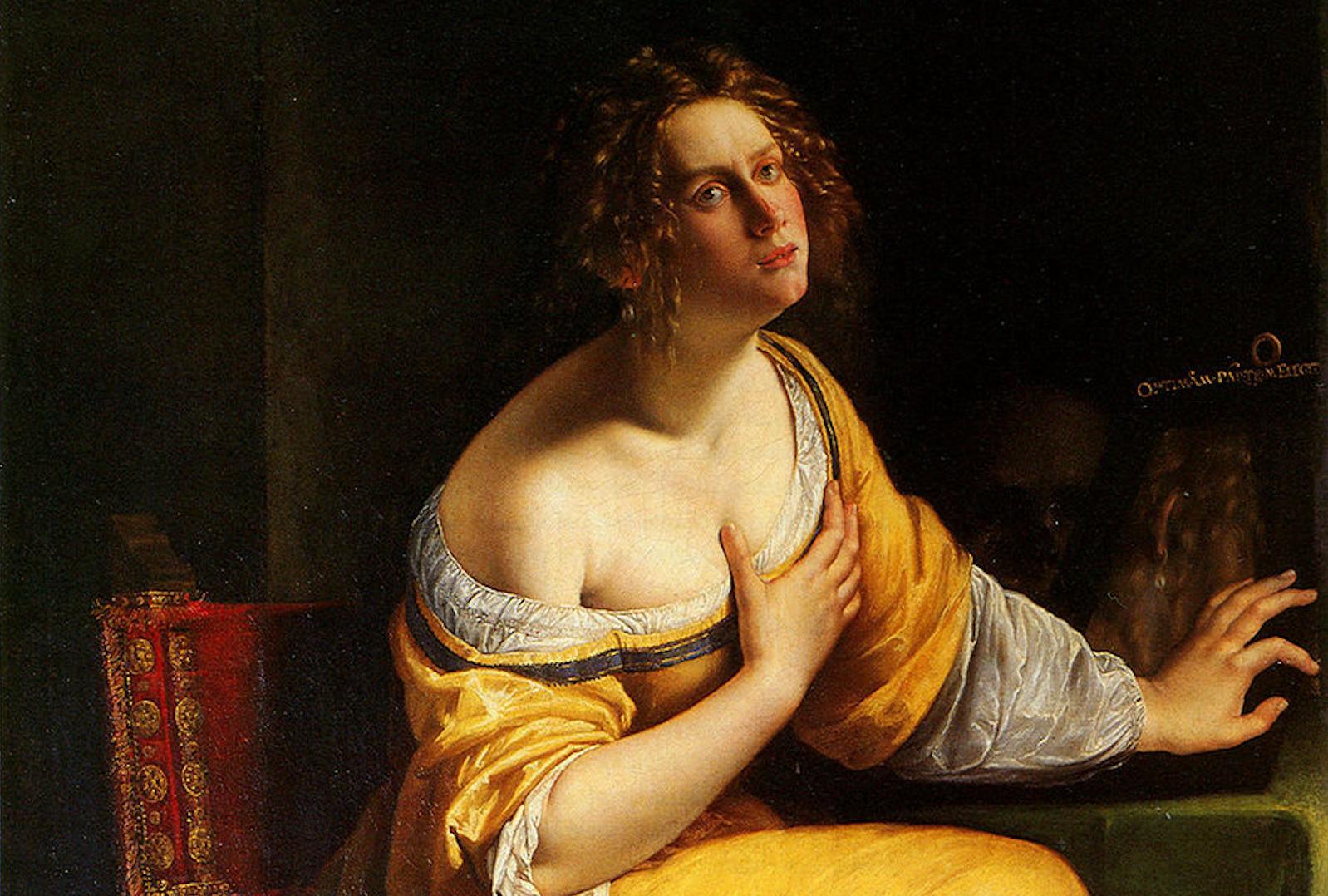

Gentileschi’s paintings of biblical heroines and icons such as the Virgin Mary, Judith, and Mary Magdalene arguably serve as opposition to the patriarchal hierarchy of the Catholic Church. Although her works were also utilized by the Counter-Reformation, Gentileschi’s emphasis on the importance of women embracing their own spirituality is prominent in Conversion of the Magdalene (1620).

This piece, among others such as Judith Slaying Holofernes (1620-21), affirmed the Protestants’ views on appointing women to positions of authority and generally embracing women’s religious lives by rejecting worldliness, hierarchy, and pride, all of which was embodied by the Catholic Church.