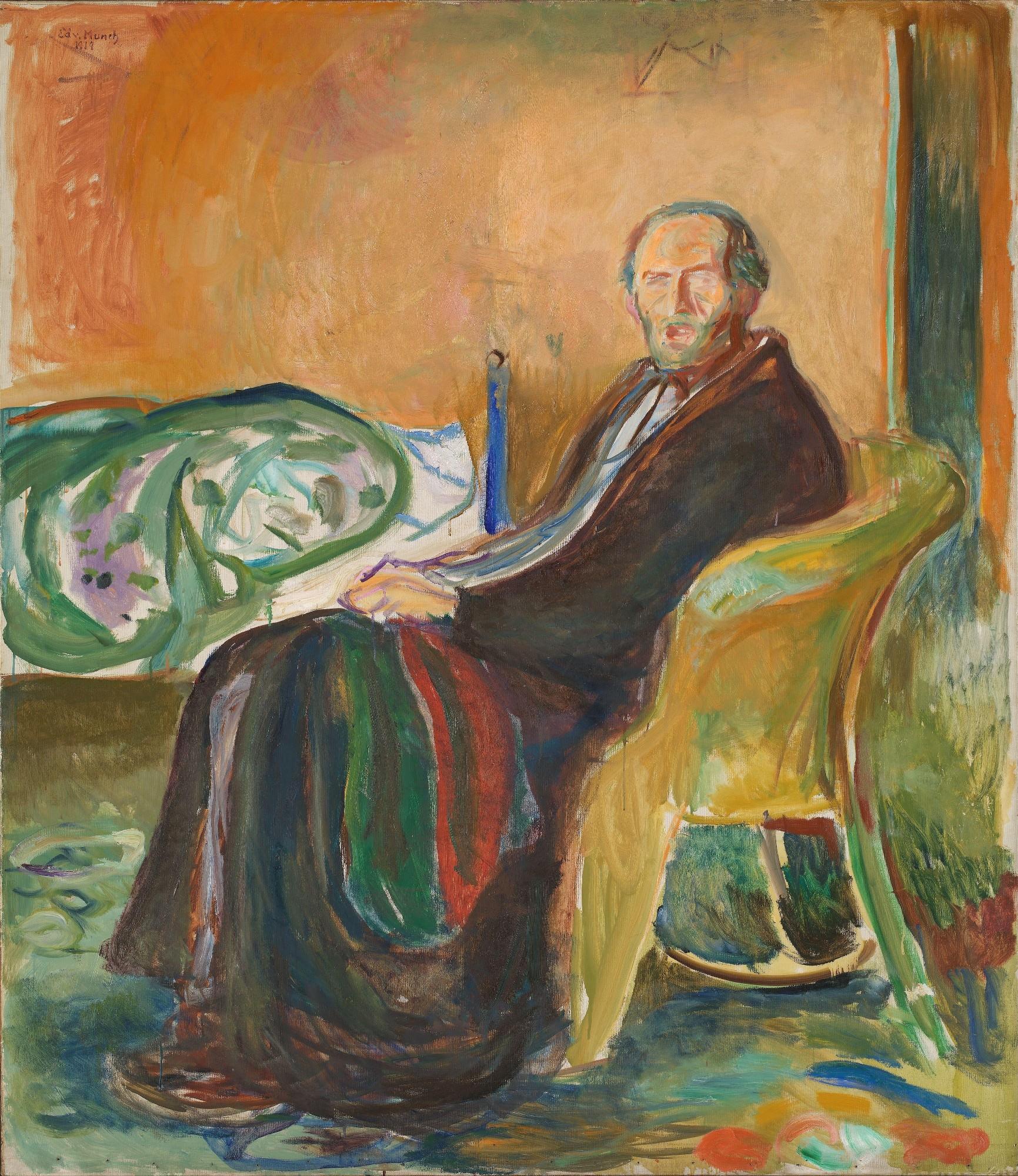

There are few notable artworks recording the actual effects of that worldwide pandemic. Edvard Munch, one of many recognizable names to have been infected, was fascinated by the disease because it drew on his long-term obsession with terminal illness. He made two noteworthy depictions of the flu’s effects: the unnerving Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu (1919) and the more macabre Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu (1919–20). But it was also in 1918 that Alfred Stieglitz was afflicted by love and began his nude photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe.

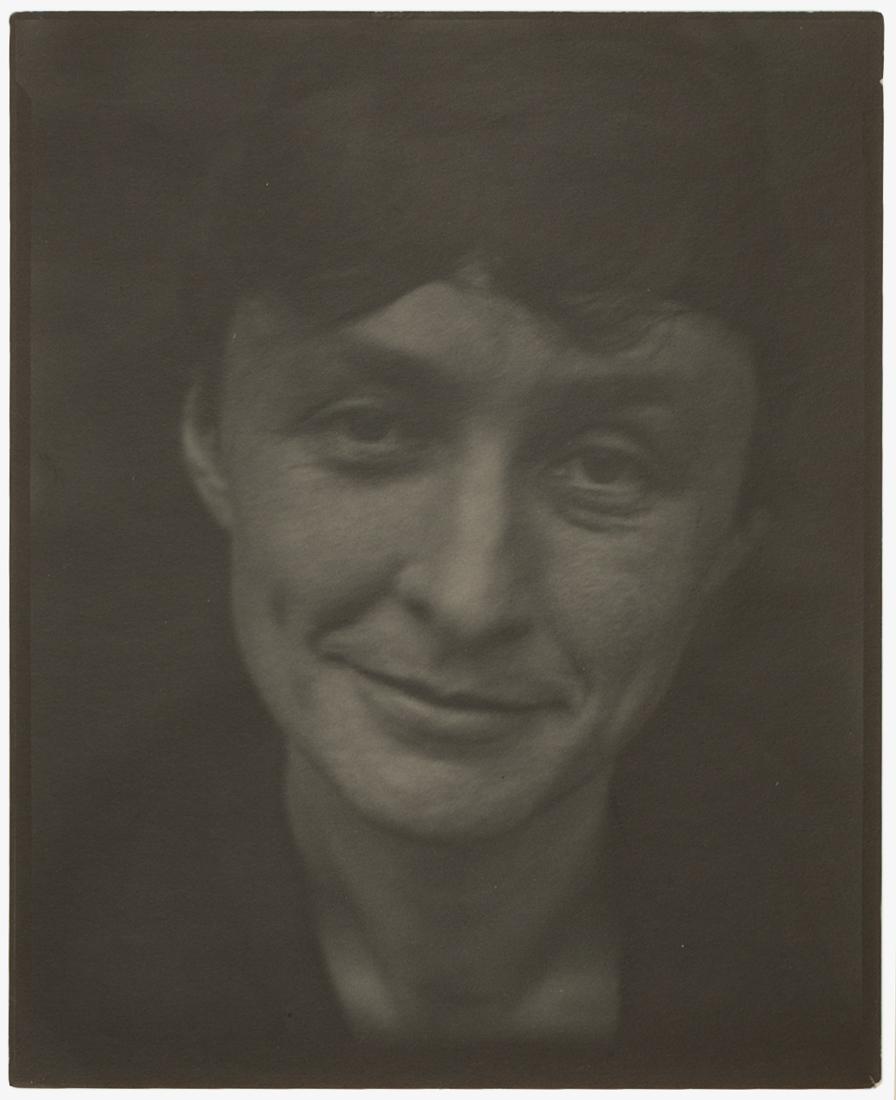

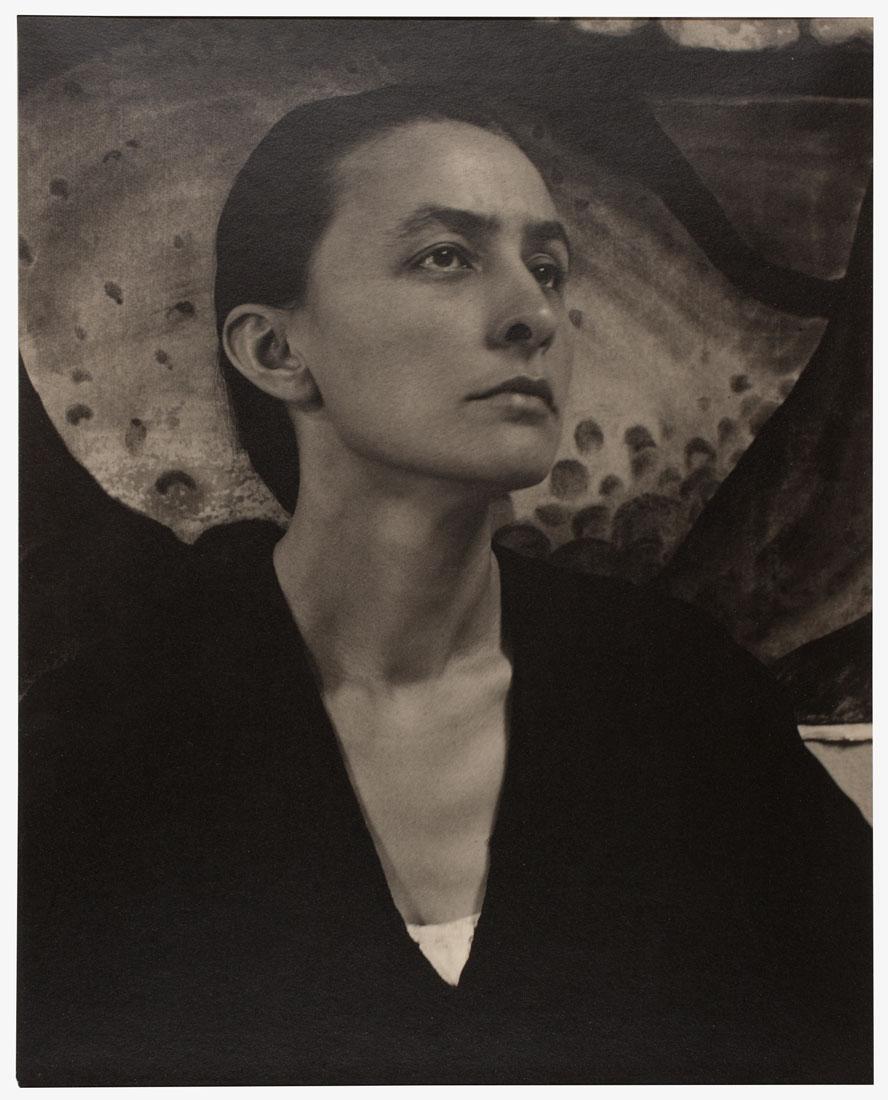

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1922.

In times of catastrophe, economies may fail, countries may collapse, and many people may die, but history tells us there are always two things that survive: love and art. The last great worldwide pandemic, the Spanish Flu, changed the world in 1918, coinciding with the winding down of World War I, which officially ended in November of that year. While we are currently struggling with quarantines, social distancing, and shutdowns of all our art institutions, it is helpful to reflect on the perseverance of artists and the survival of love during the twelve long months of 1918.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918.

Earlier, in 1916, when Stieglitz and O’Keeffe met, he was 52 and famous, she was 28 and unknown. He was an internationally acclaimed photographer who ran 291, an influential avant-garde gallery in midtown Manhattan where he introduced European artists including Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, and the Dadaists Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp to the United States. She was a Texas schoolteacher and promising young artist still finding her unique voice.

Their tumultuous love affair and marriage was recorded in over 25,000 letters written between the years 1915 and 1946, tracking their evolution from acquaintances to admirers, to lovers and ultimately man and wife. O’Keeffe writes from Canyon, Texas, on November 4, 1916, "I'm getting to like you so tremendously that it sometimes scares me," and, " ... Having told you so much of me—more than anyone else I know—could anything else follow but that I should want you — ."

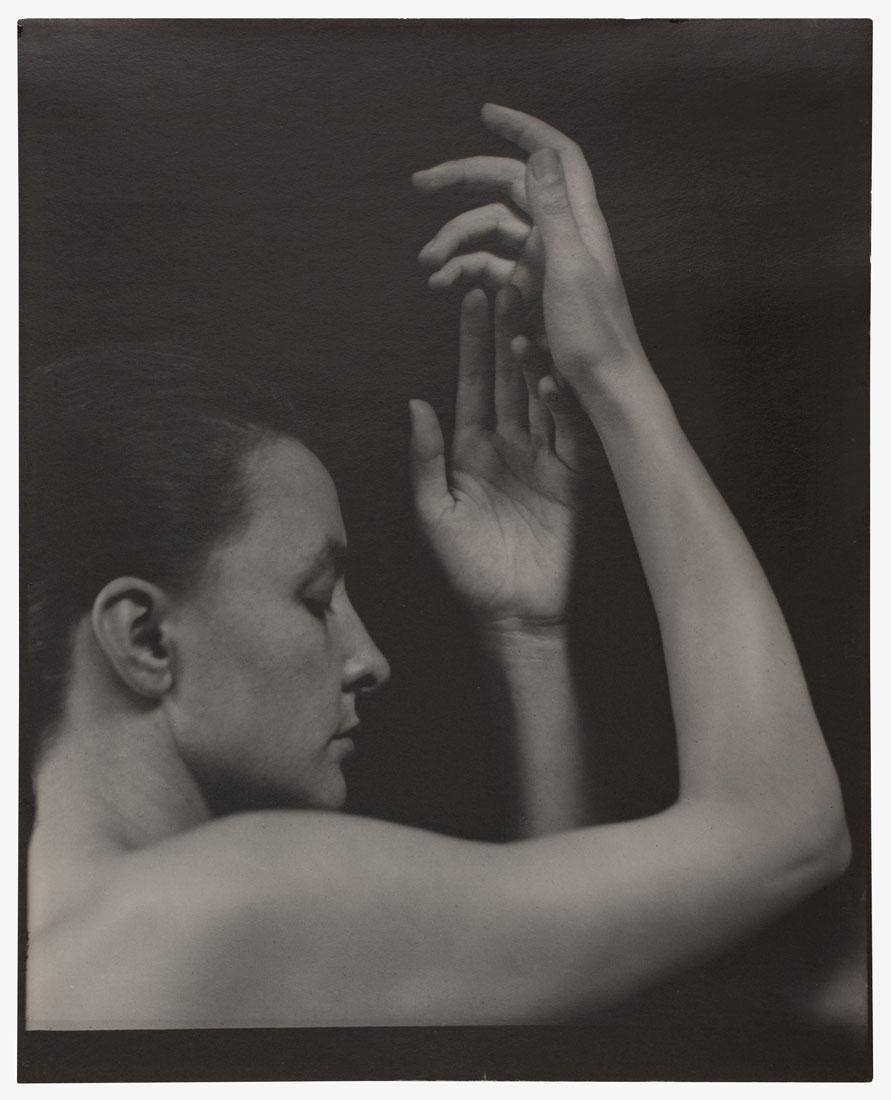

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1919/20.

O’Keeffe clearly is enamored of Stieglitz. He became her mentor and exhibited her work in his prestigious gallery, giving her a solo exhibition there in April 1917. O’Keeffe came to New York and then, as she's about to return to Texas, Stieglitz wrote to her on June 1, 1917: "How I wanted to photograph you—the hands—the mouth—& eyes—& the enveloped in black body—the touch of white—& the throat—but I didn't want to break into your time—."

The two continued their long-distance courtship until the spring of 1919 when O’Keeffe contracted the Spanish Flu in Texas. As part of her convalescence, she decided to move to New York permanently, so that Stieglitz could care for her. Though he was married to another woman, the two had fallen in love. He wrote to her on May 26, 1918: "What do I want from you?— ... Sometimes I feel I'm going stark mad—That I ought to say—Dearest—You are so much to me that you must not come near me—Coming may bring you darkness instead of light—And it's in Everlasting light that you should live."

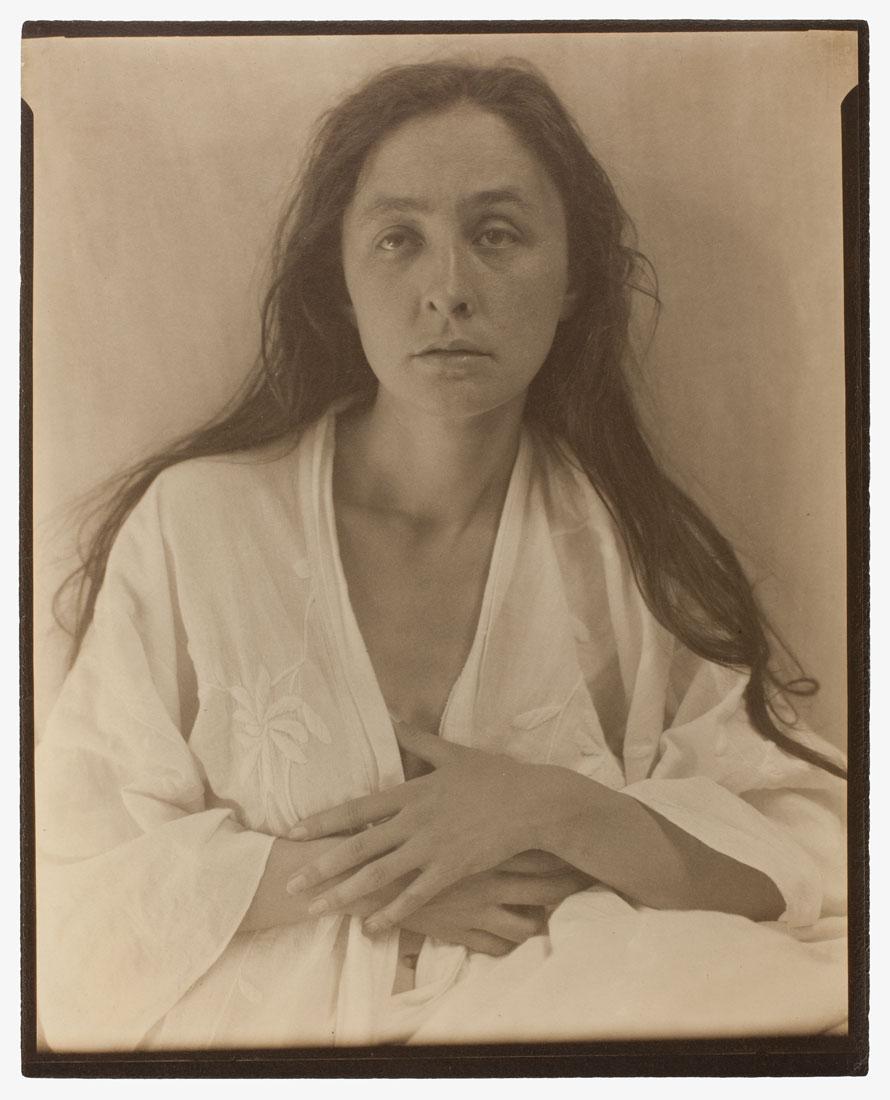

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918.

Although Stieglitz created over 300 photographs of O’Keeffe throughout their long relationship, it was in 1918, when the heat of their love was brand new and the world was in chaos, that his camera lens became the instrument of his passion, exploring every inch of her face, her long graceful limbs and naked body often in languid repose. It was her illness that ultimately united them, as Stieglitz helped her recover and was thus forced out of his marriage.

It is estimated that over 20 million people worldwide died during the 1918-19 flu pandemic, while at the same time, many lives were being lost in World War I. O'Keeffe suffered extreme anxiety related to her antiwar stance and concern for her brother who was shipped overseas to fight in France. In this intense atmosphere, their passionate love burned bright, fueling them artistically and spiritually in the face of the ruins of World War I and the invisible enemy of the disease.

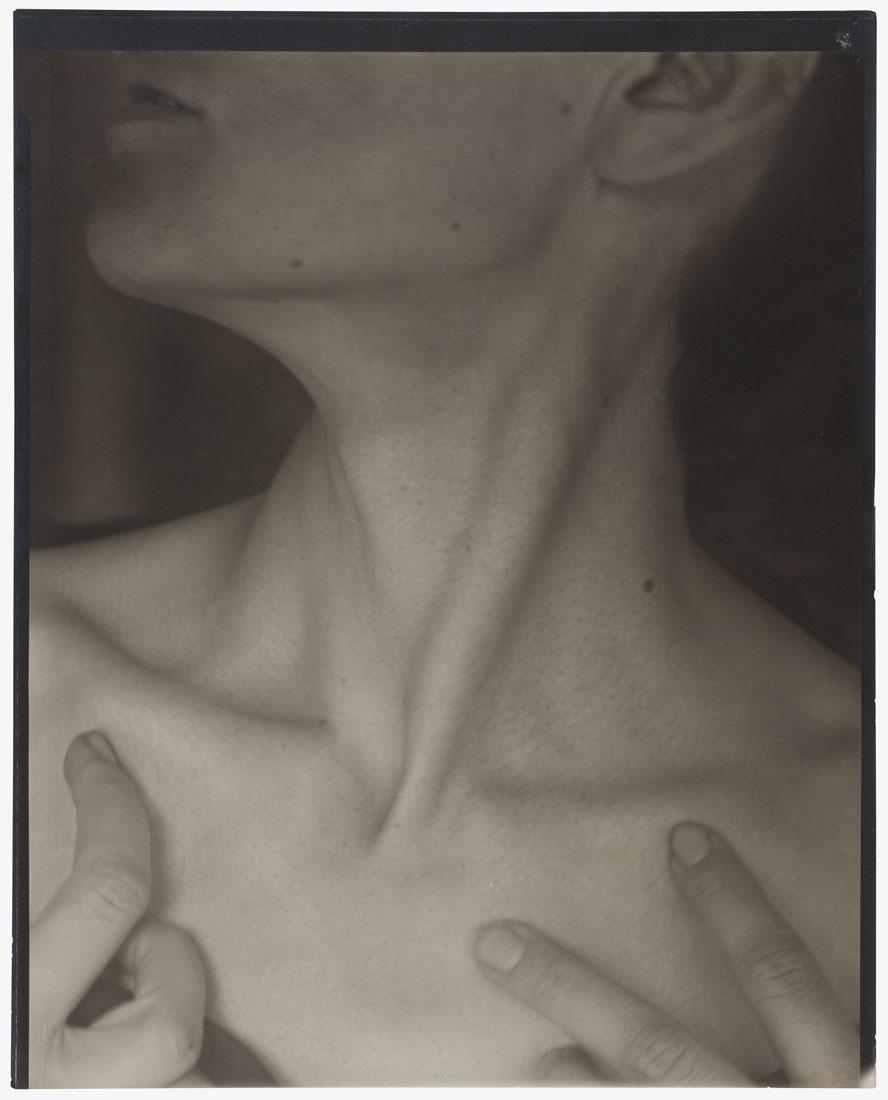

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918.

In 1919 Stieglitz wrote, “I am at last photographing again. . . . It is straight. No tricks of any kind.—No humbug.—No sentimentalism.—Not old nor new.—It is so sharp that you can see the [pores] in a face—& yet it is abstract. . . . It is a series of about 100 pictures of one person—heads & ears—toes—hands—torsos—It is the doing of something I had in mind for very many years.”

In spite of giving Stieglitz access to her physicality, O’Keeffe remained elusive, as is most evidenced in her enigmatic expression that seldom revealed her innermost thoughts or feelings. It is the artist part of her that she protected, and though their love was mutual, it is the artist in O’Keeffe that won out. After ten tumultuous years with Stieglitz, in 1929 O’Keeffe went to New Mexico and again, fell in love, this time with a place that captured her imagination and became the focus of her art for the remainder of her life. She moved there permanently in 1949.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe—Neck, 1921.

After Stieglitz’s death in 1946 O’Keeffe became the executor of his estate, dividing his archive among several institutions including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The National Gallery of Art, among others. Georgia O’Keeffe died in Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1986 at the age of 98.