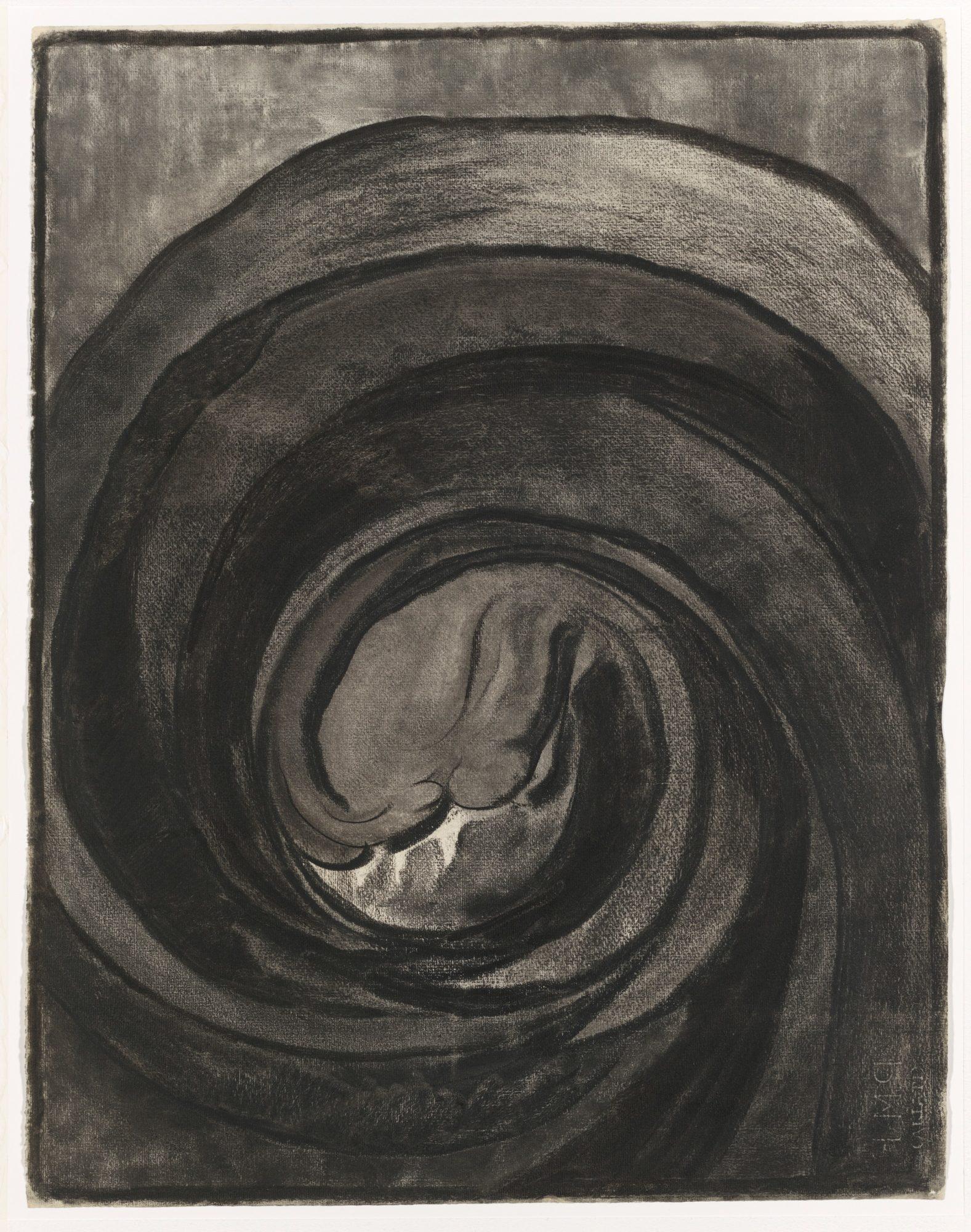

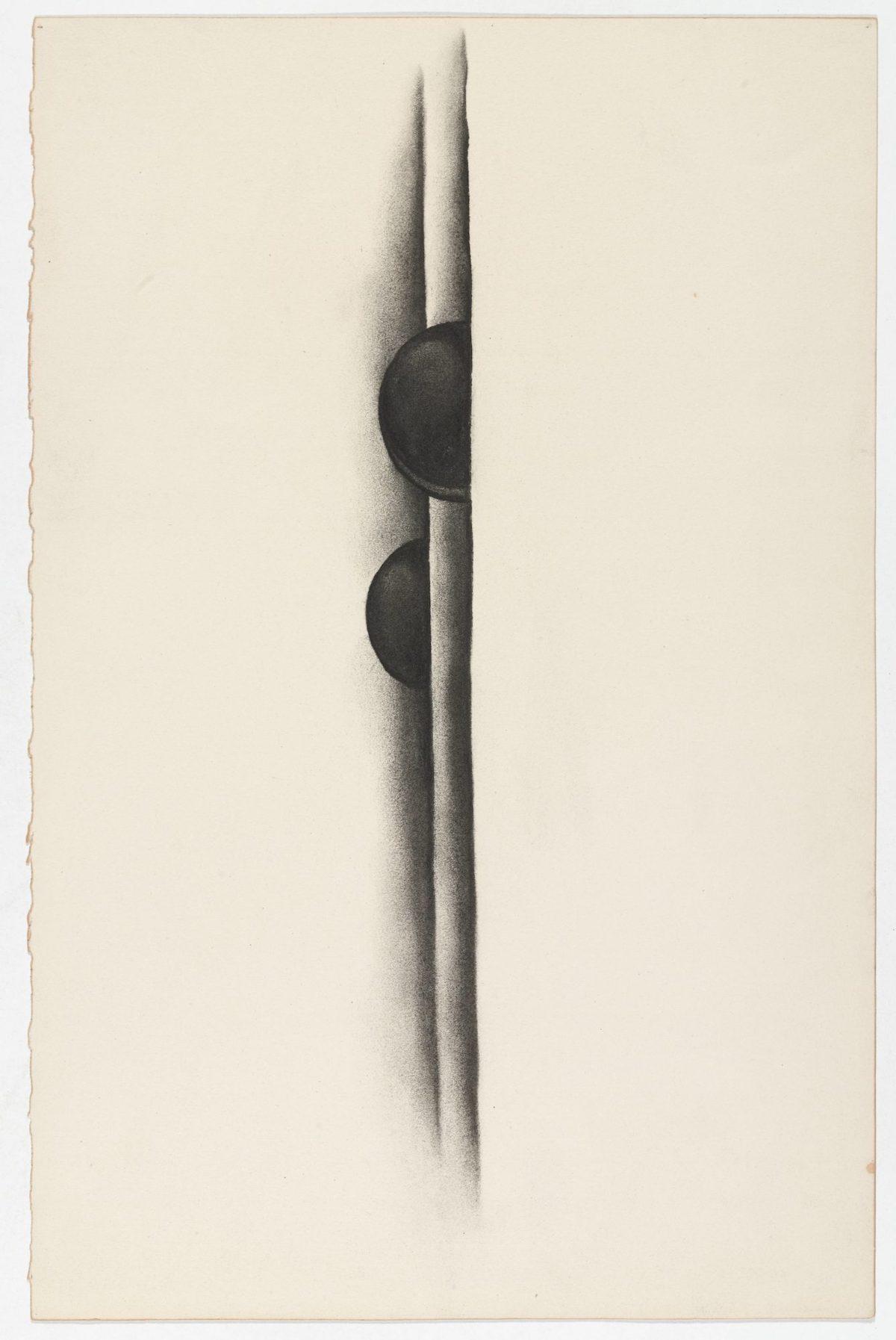

Without O’Keeffe’s knowing, Pollitzer sent sixteen of these drawings to the famous photographer and impresario of modern art, Alfred Stieglitz. A few months later he included ten in a group show in New York City in his gallery 291. He felt her charcoal drawings were an expression of female intuition. O’Keeffe was furious that he had exhibited the work without her permission. The rest, as they say, is history. Stieglitz introduced O’Keeffe to the world, they fell in love and married, and she became the most famous and celebrated woman artist of the twentieth century.

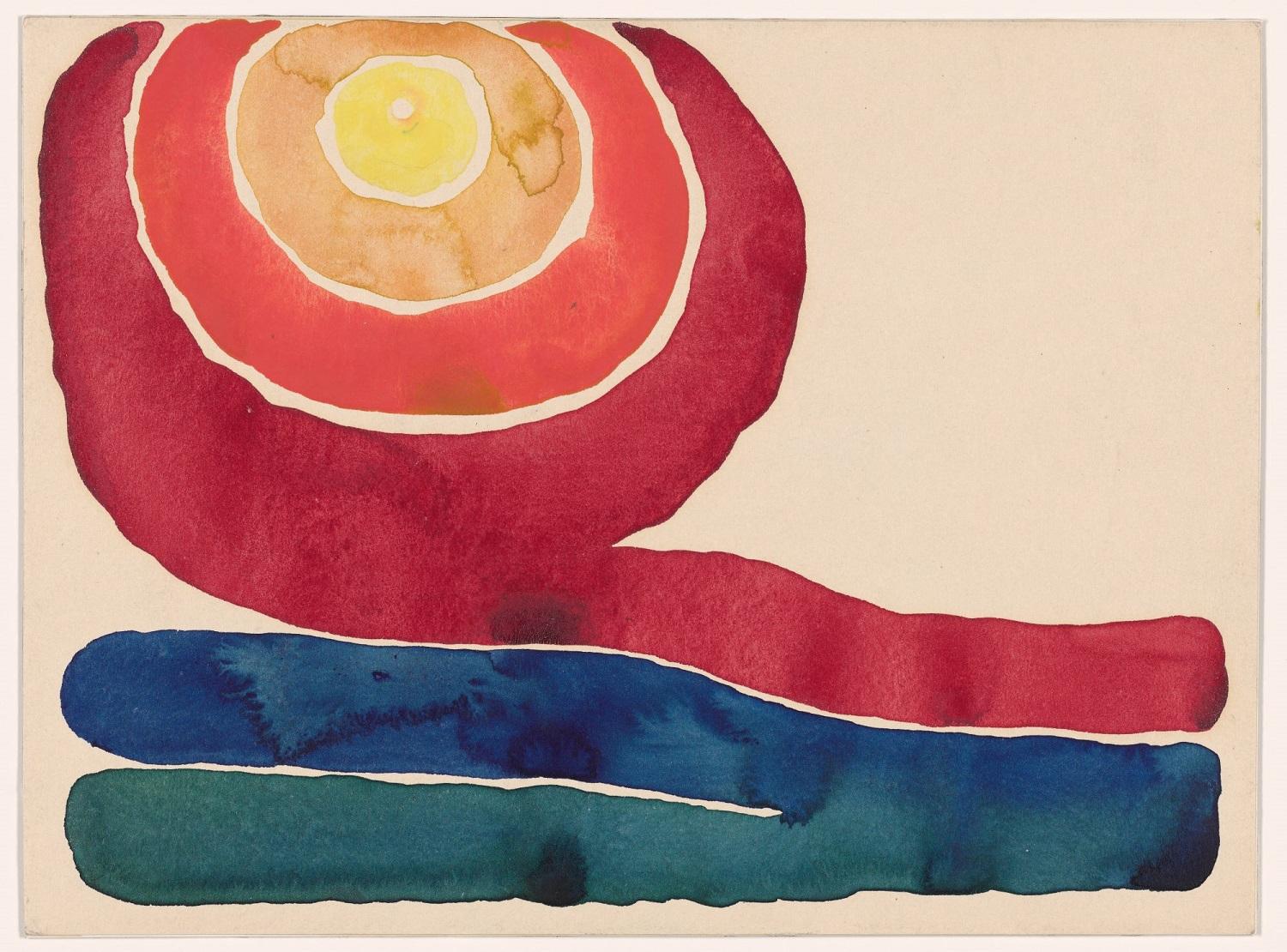

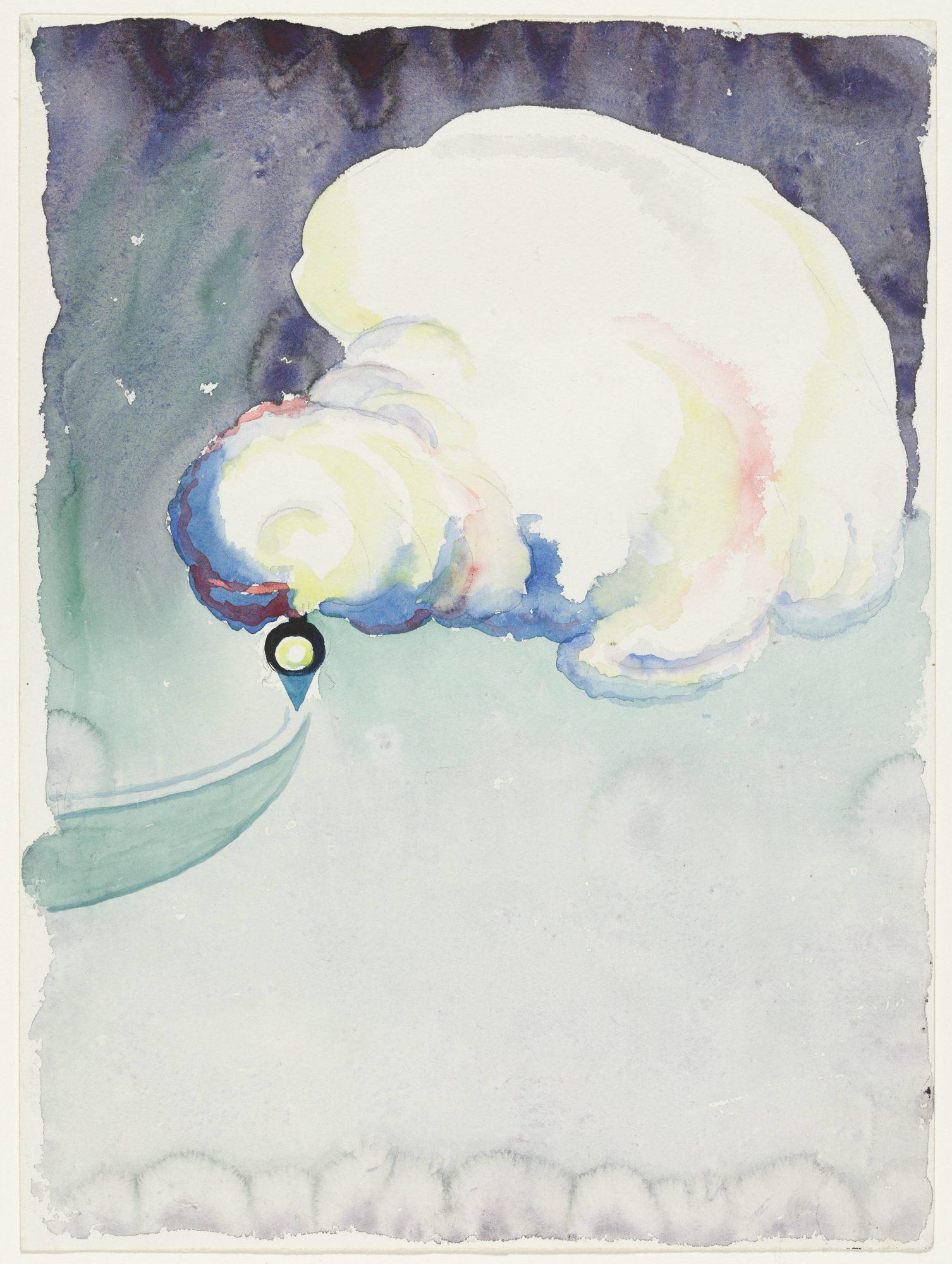

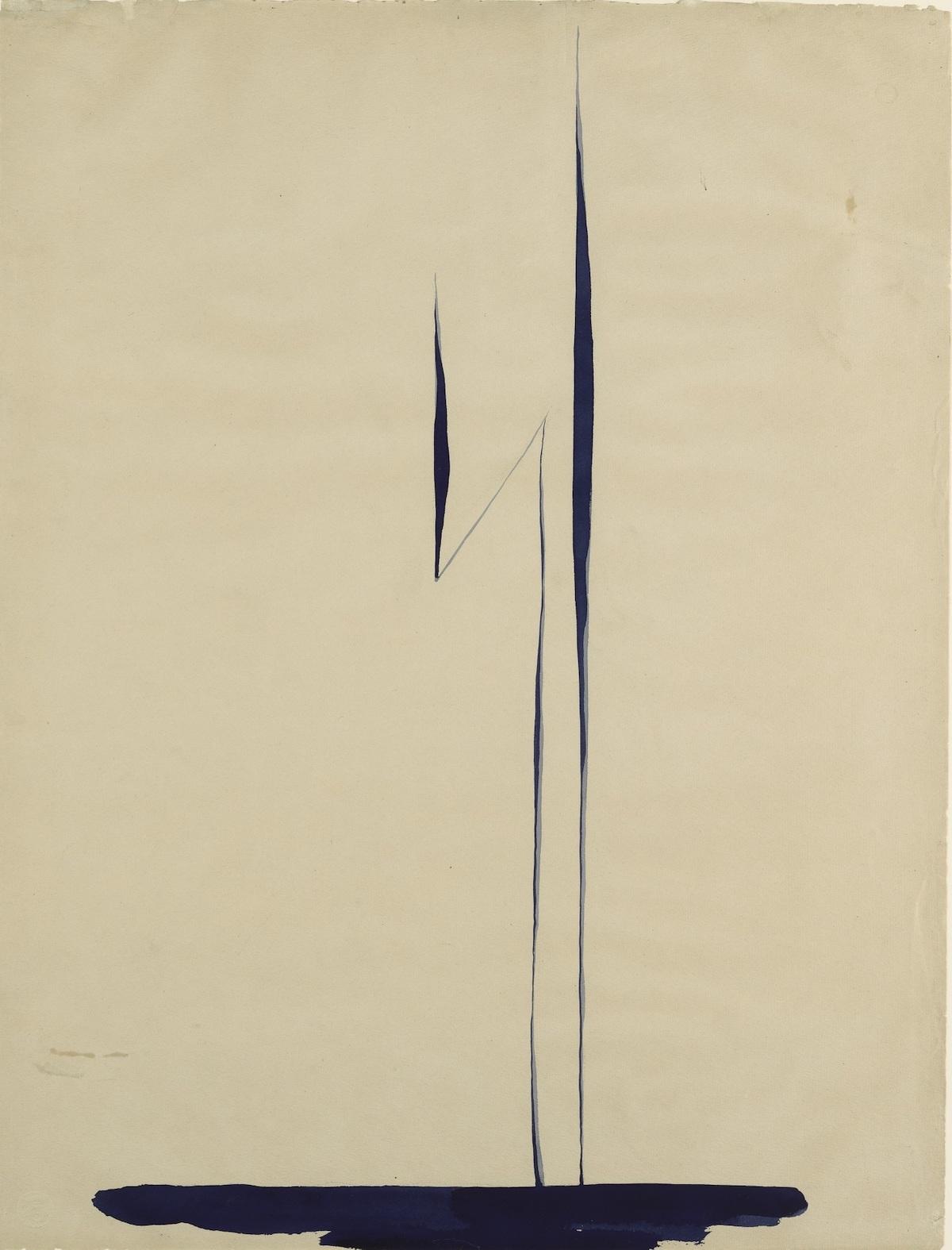

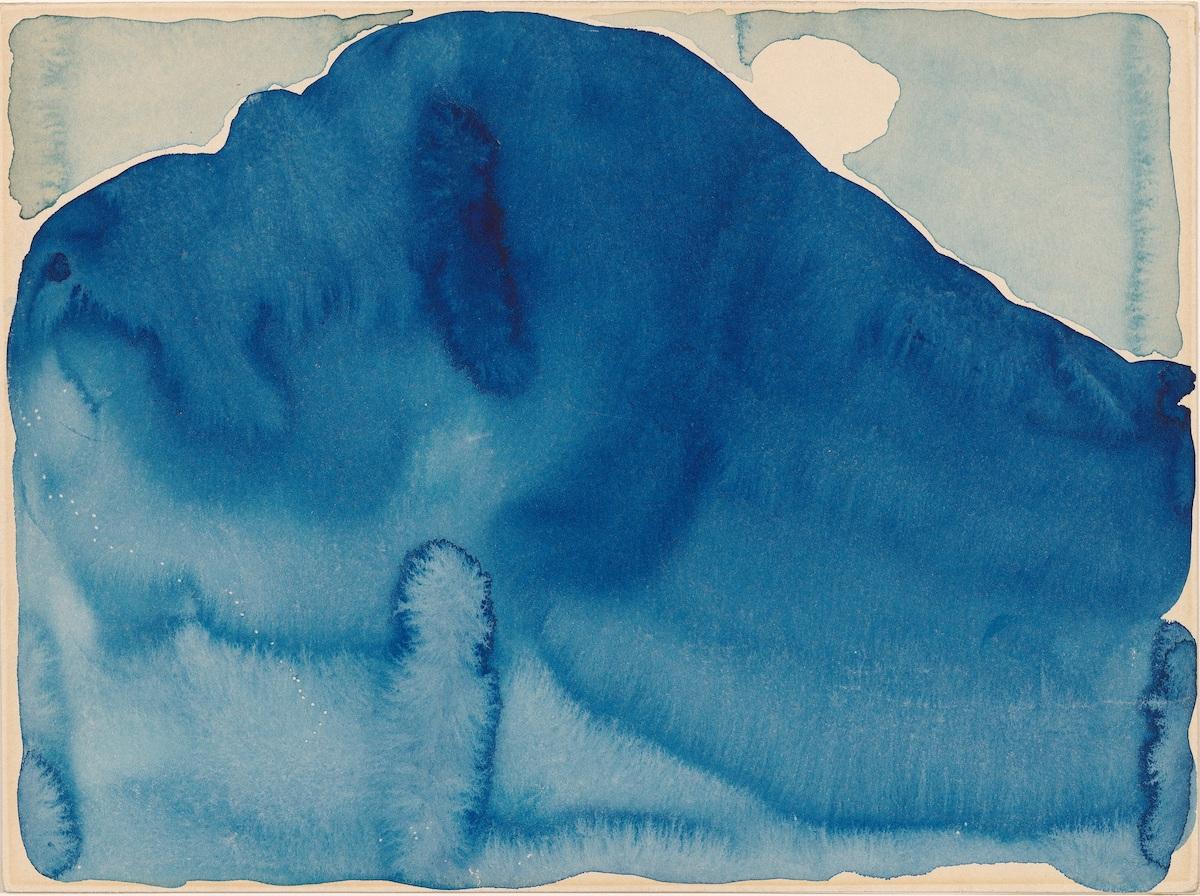

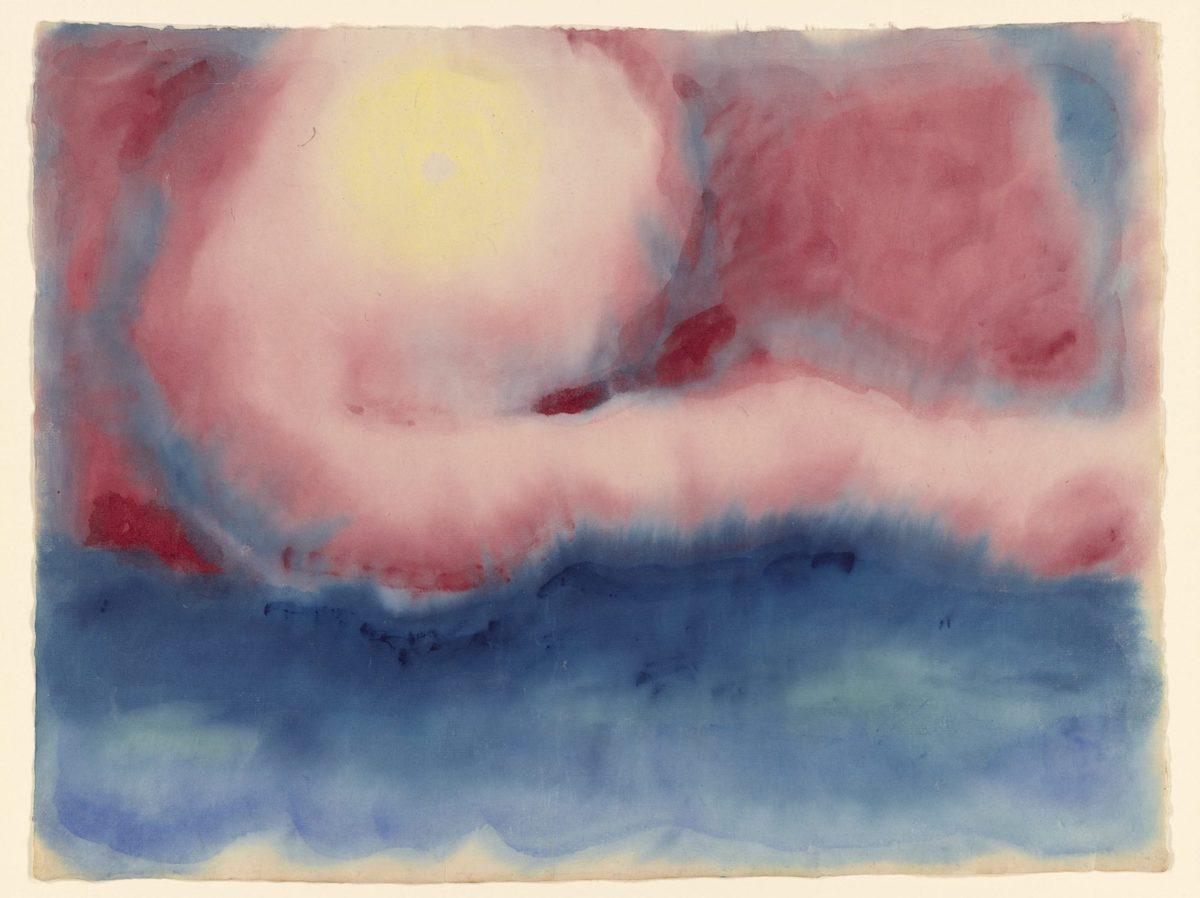

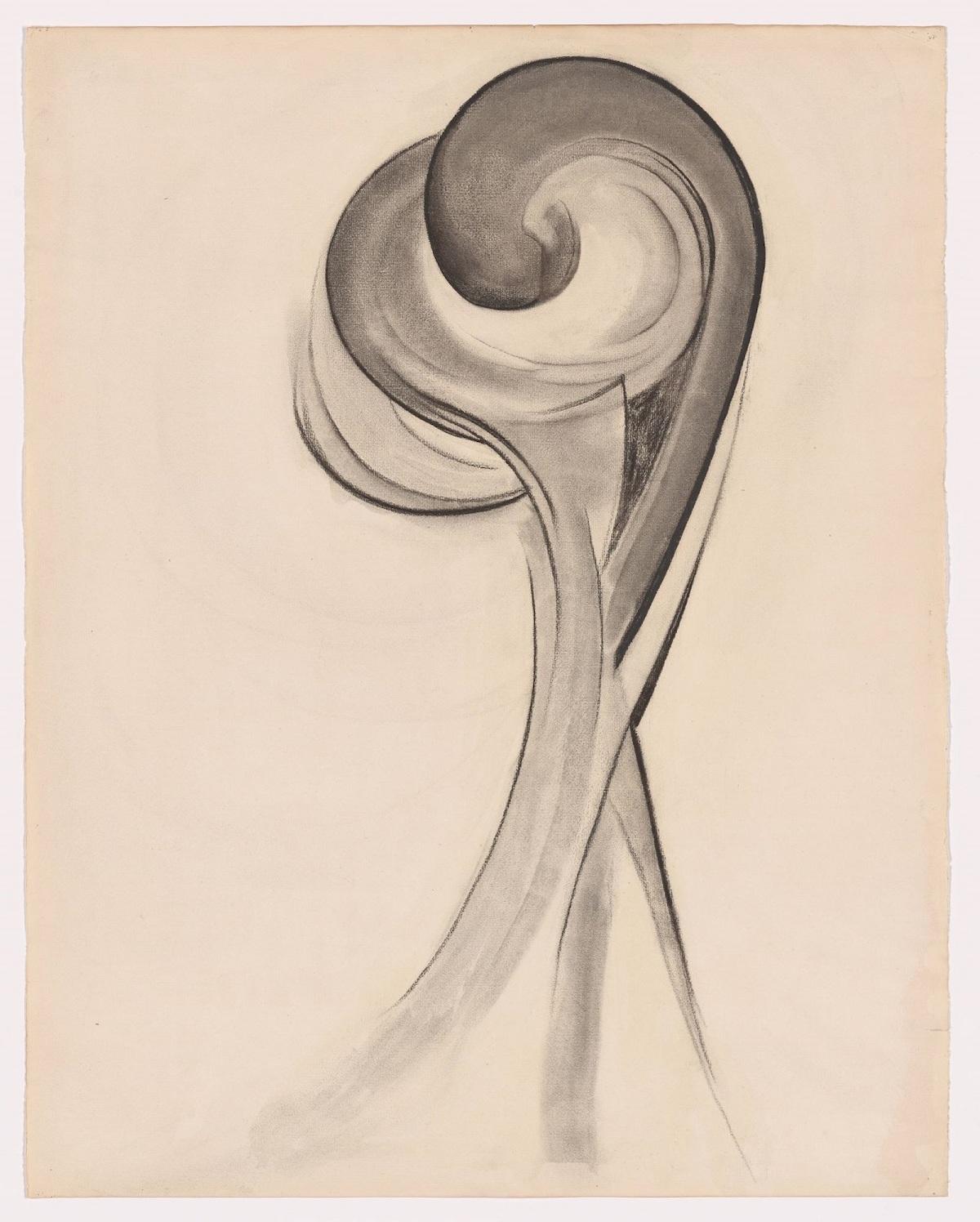

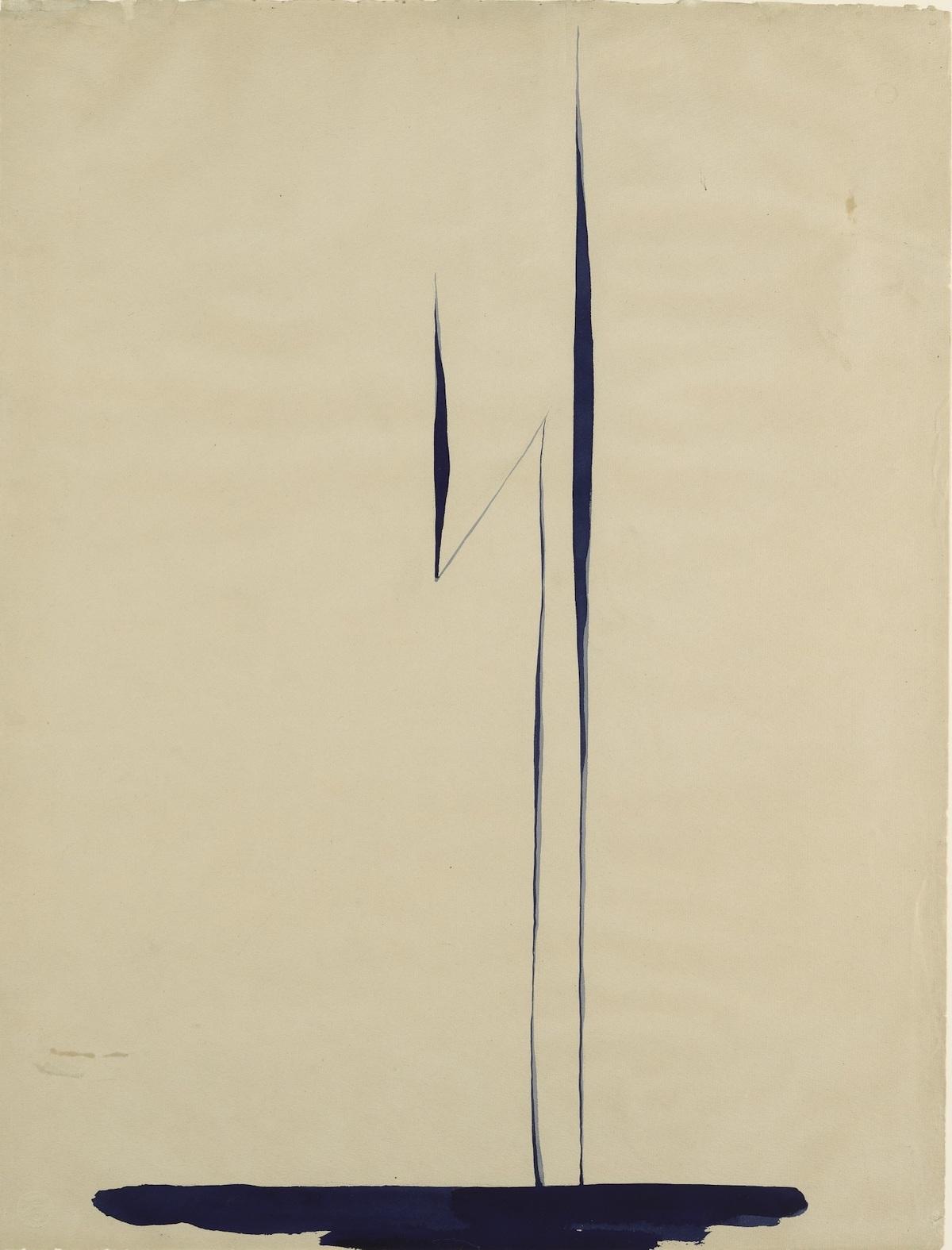

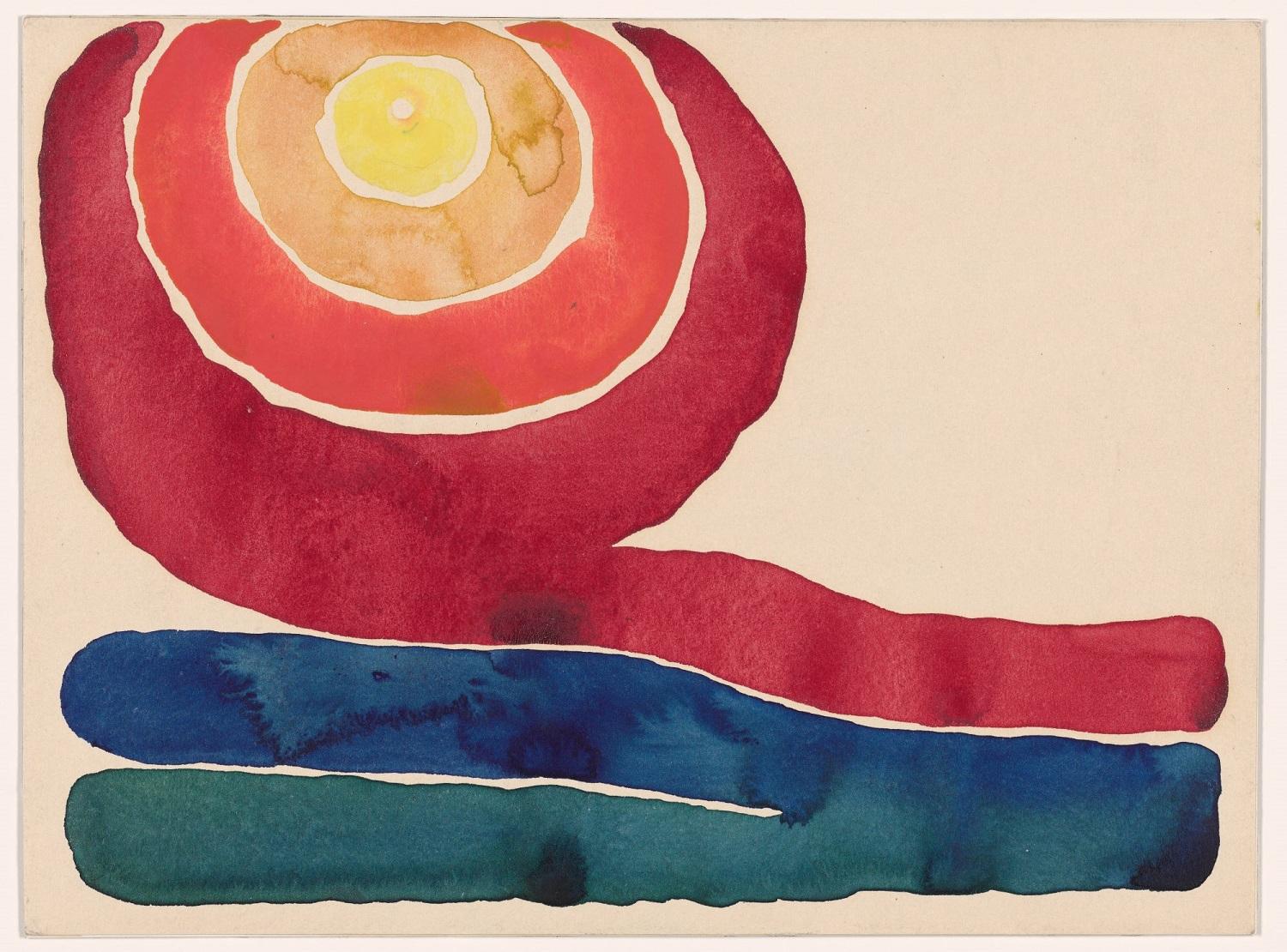

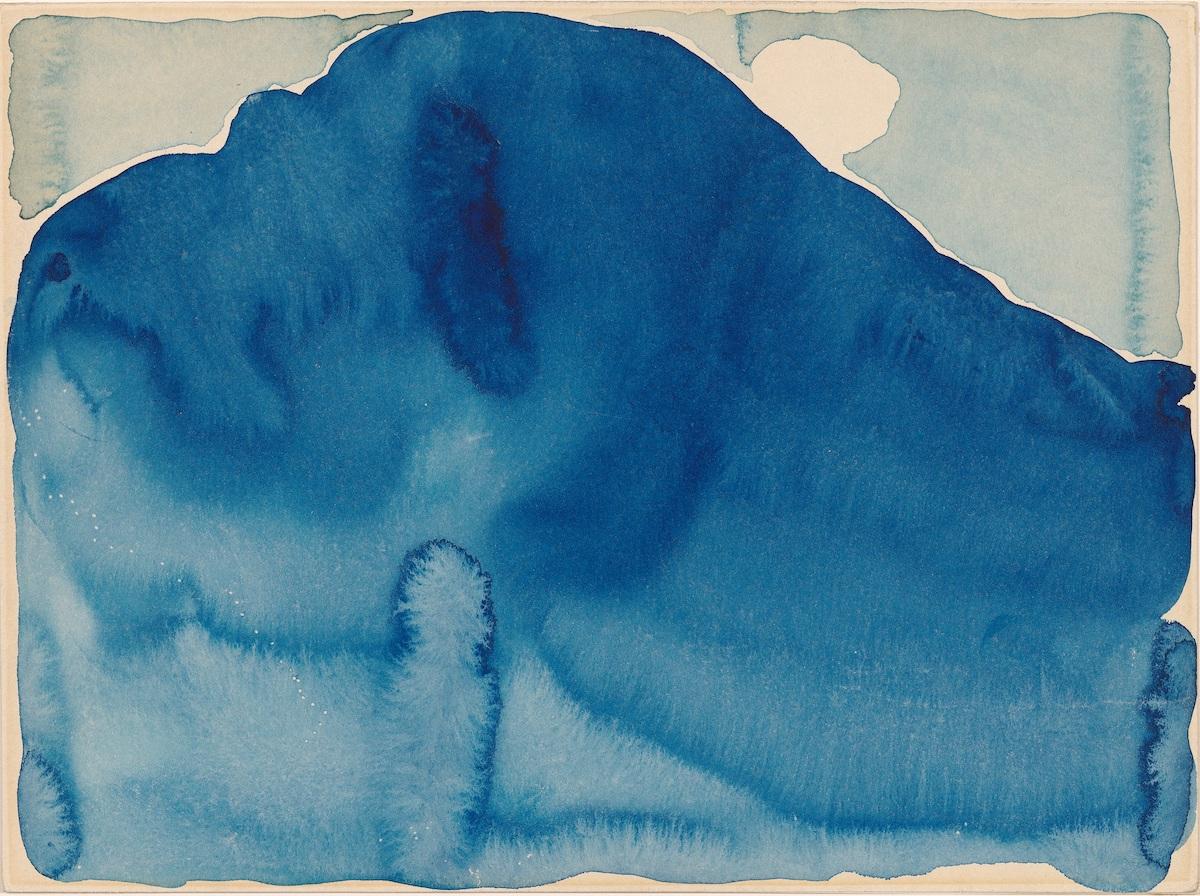

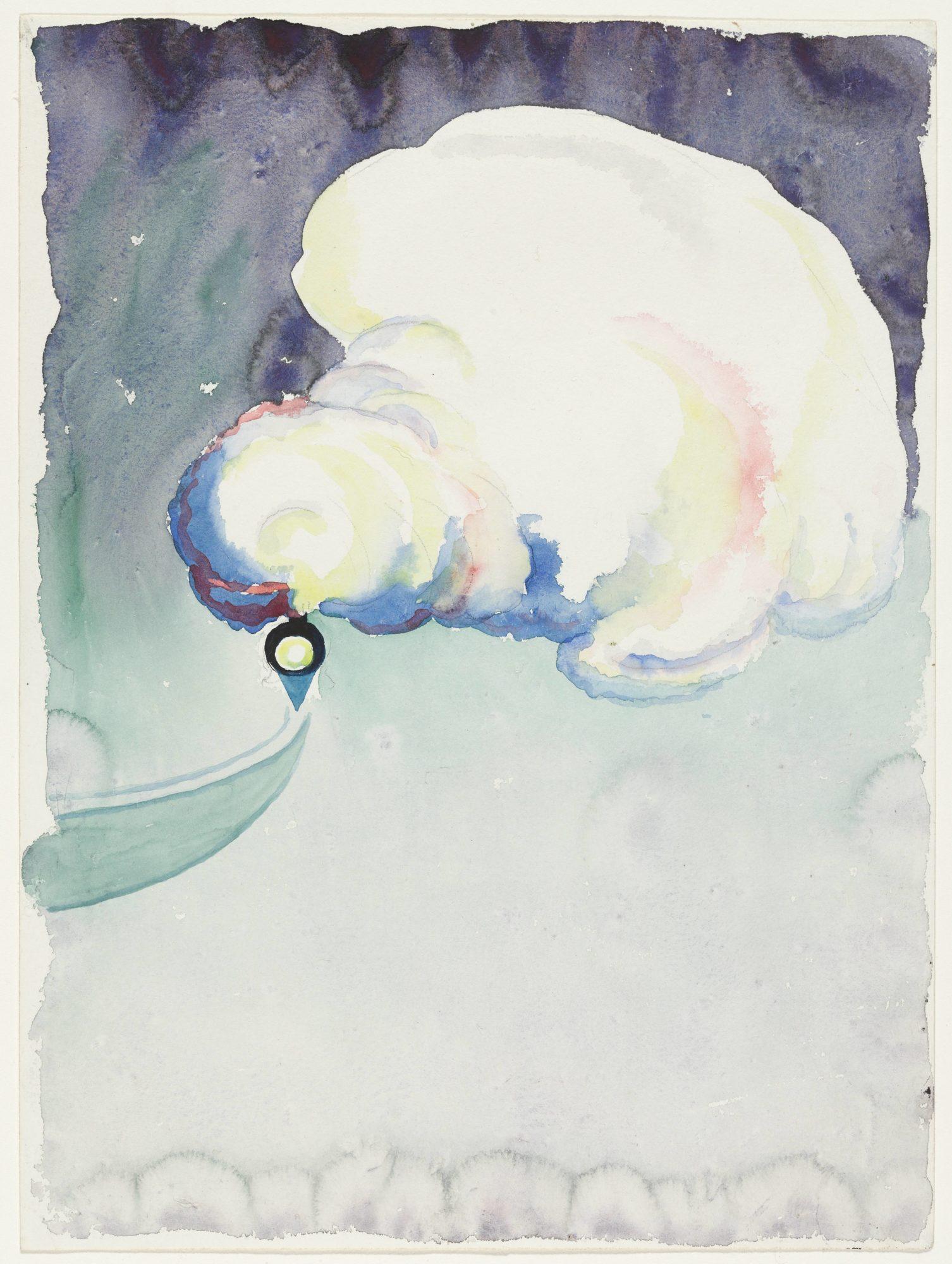

Her legacy is the ever popular, up-close and colorful flower paintings. As sensational as these are and certainly evocative—male critics found them to be sexual, an interpretation that she refuted—her innovation and profound influence are her early drawings, watercolors, and pastels. Here we see a young artist making work that was radical and new, in a language all her own. The work is spirited, original, mysterious, and exciting. Speaking about these early drawings and watercolors in 1969, on the cusp of her retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, O'Keeffe told her good friend, Doris Bry, the co-curator of the 1970 retrospective, “We don’t really need to have the show, I never did any better.”

At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), through August 12, 2023, is a series of the artist’s works on paper: Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time. The exhibition features 120 charcoal, watercolor, pastel, and graphite works O’Keeffe created over a forty-year time span, beginning with the 1916 charcoal drawings that Stieglitz first exhibited.