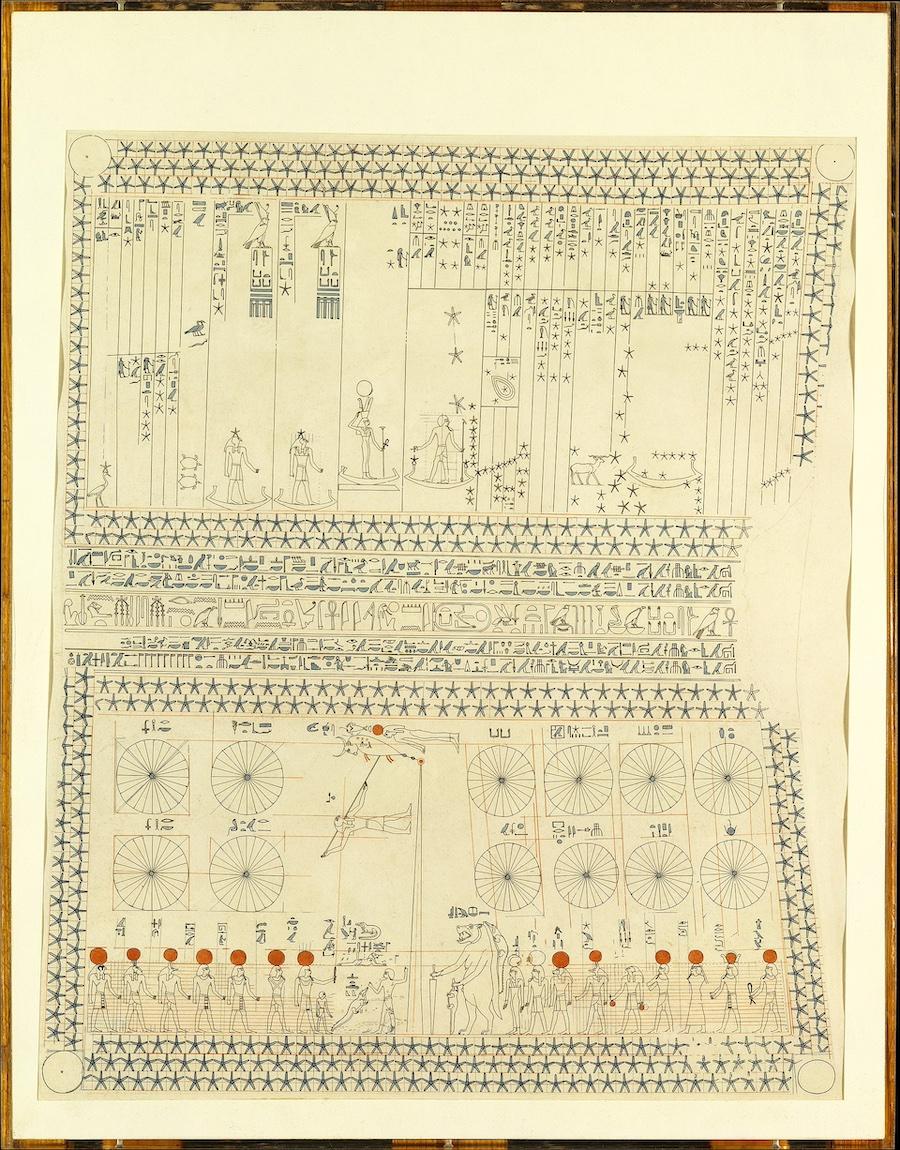

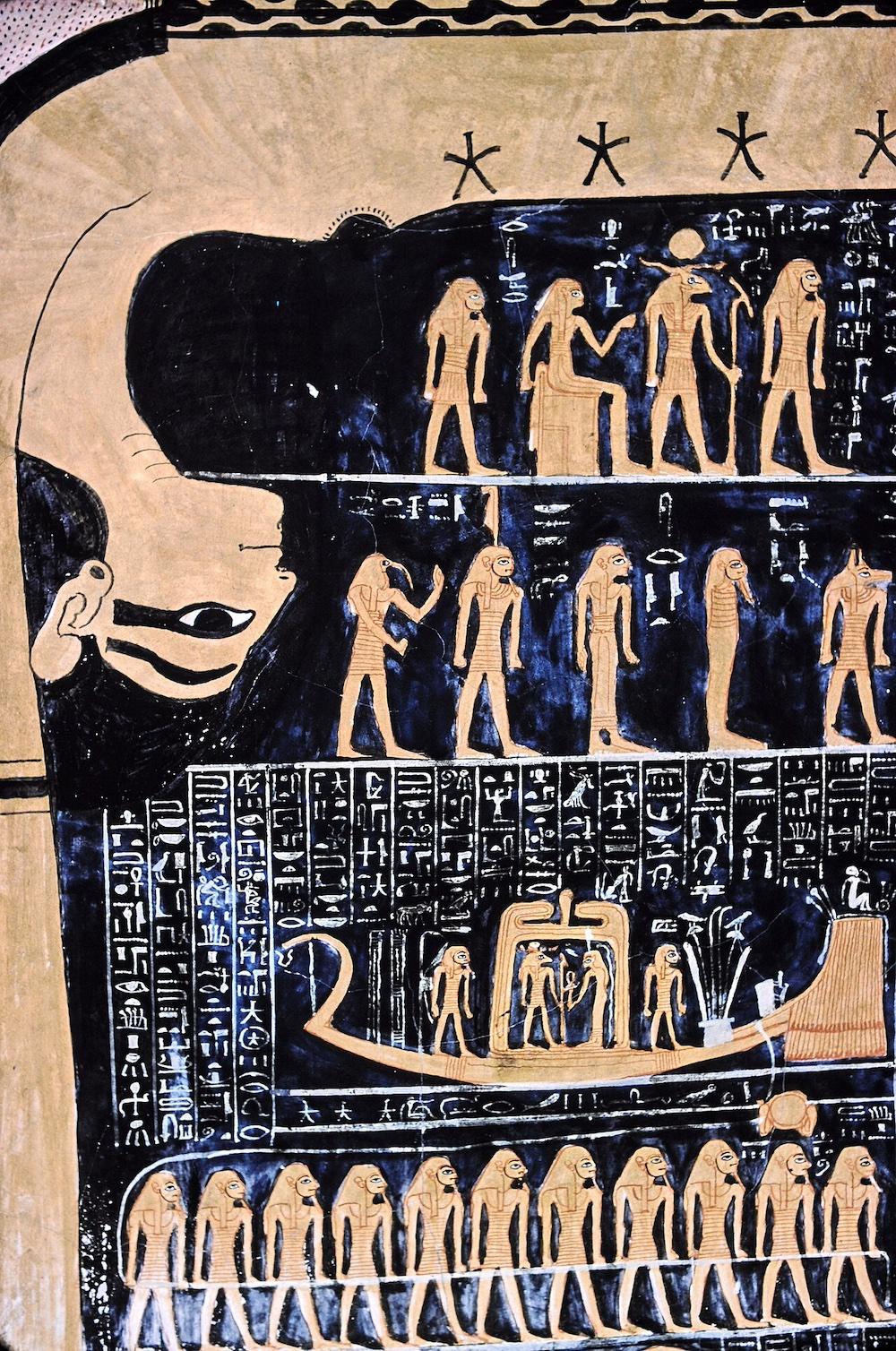

From the union of Geb and Nut then came many other prominent Egyptian deities such as Osiris, Isis, and Set. Of course, this is an extremely simplified version, but one mythical variation of creation, as many of the major ancient Egyptian cities had their own versions. What does seem to have had a significant amount of similarity, though, is how these deities of the sky and its contents were portrayed in papyri, carvings, and paintings.

Many Egyptian deities, like in other ancient cultures, were predominately depicted in human or at least human-esque guises. Atum, Ra, and Nut all have personifications of anthropomorphic persuasions with their own unique particularities and meanings that changed throughout time.

Atum, for instance, is most often seen as a man wearing either a divine wig or the dual crown of both Lower and Upper Egypt, signifying his connection to kingship as the creator of the world. In some visual iterations, Atum is depicted as an older man leaning on a stick, referring to his role as the setting sun, while in other solar depictions, he is seen as a scarab beetle.