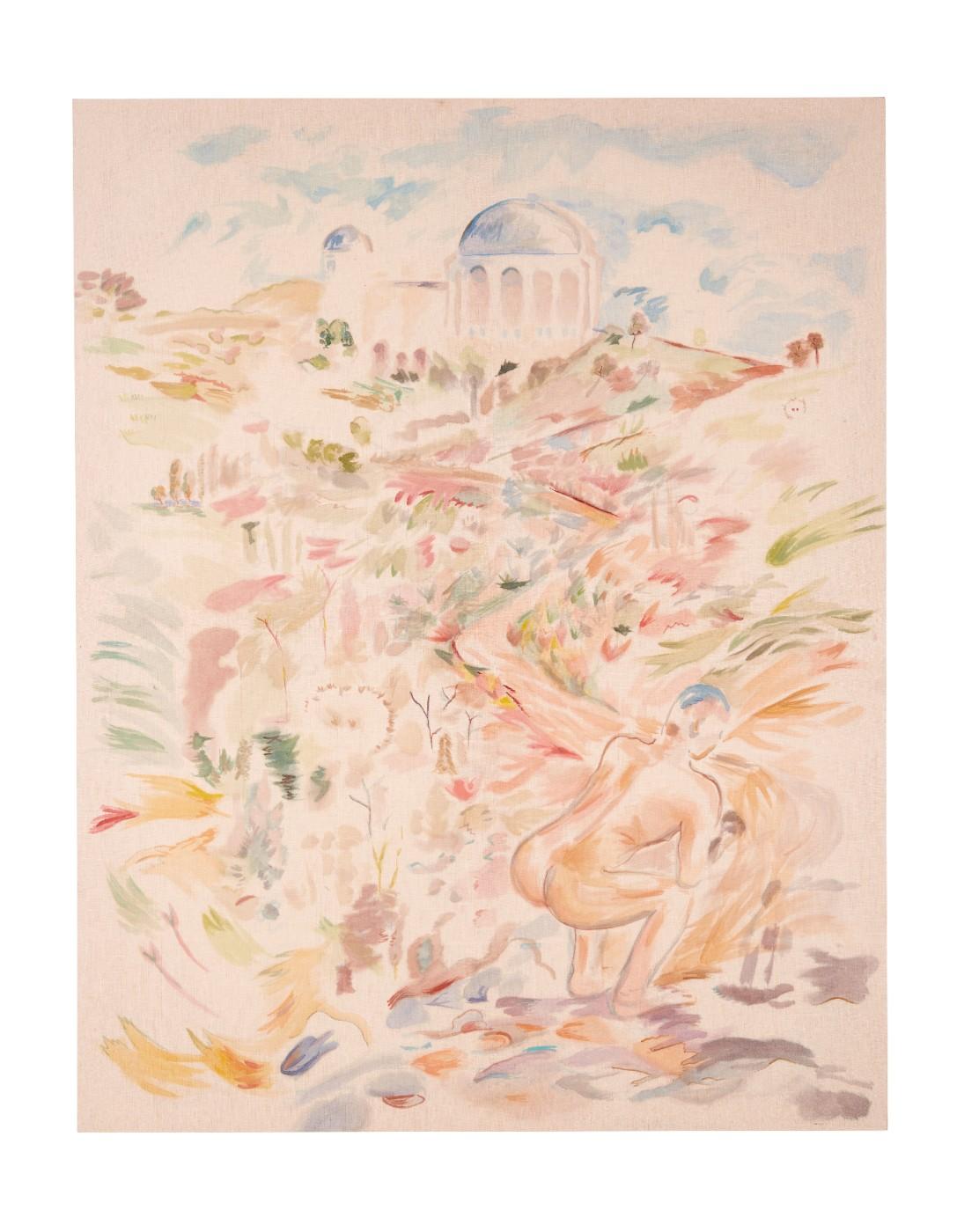

“If you were an abstract painter, you might, when you’re in school, learn to paint like Da Vinci, see how far you can go in different directions,” Van Sant tells Art & Object on a recent sunny late summer morning over coffee on his patio overlooking the Hollywood sign and Griffith Observatory. “Chuck Close was asked how do you arrive at that thing you're known for? And his answer was you do everything until finally something gets you going in the public eye and you freeze into that.”

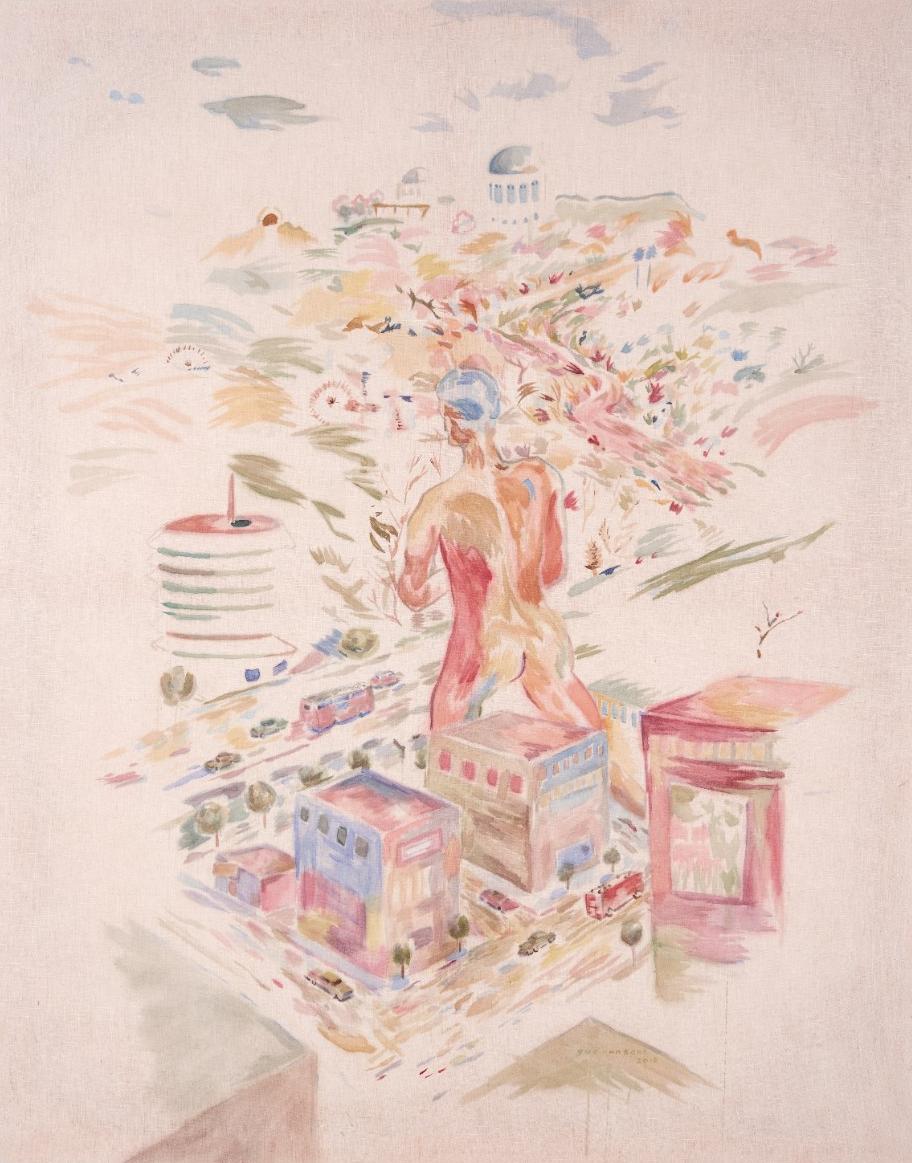

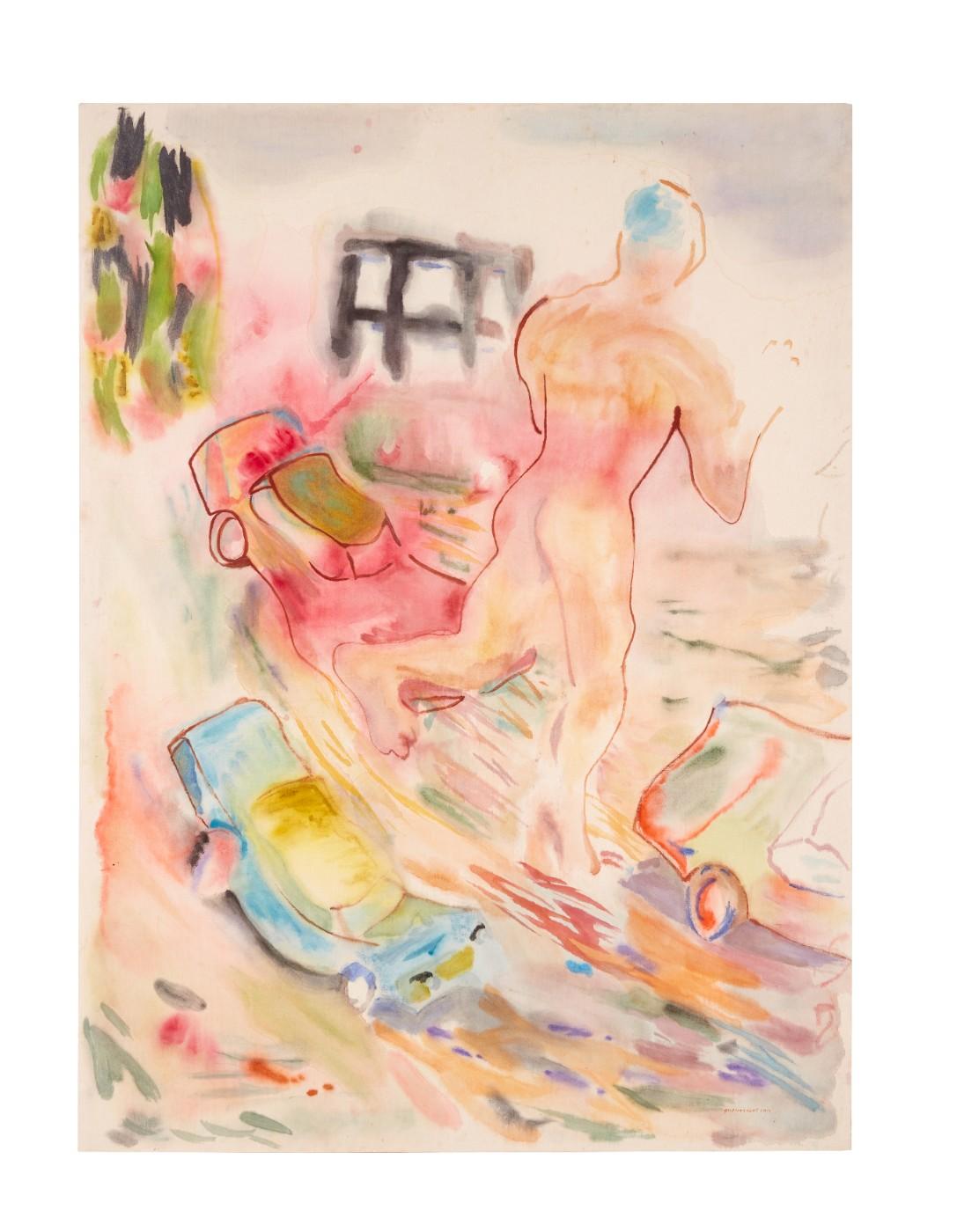

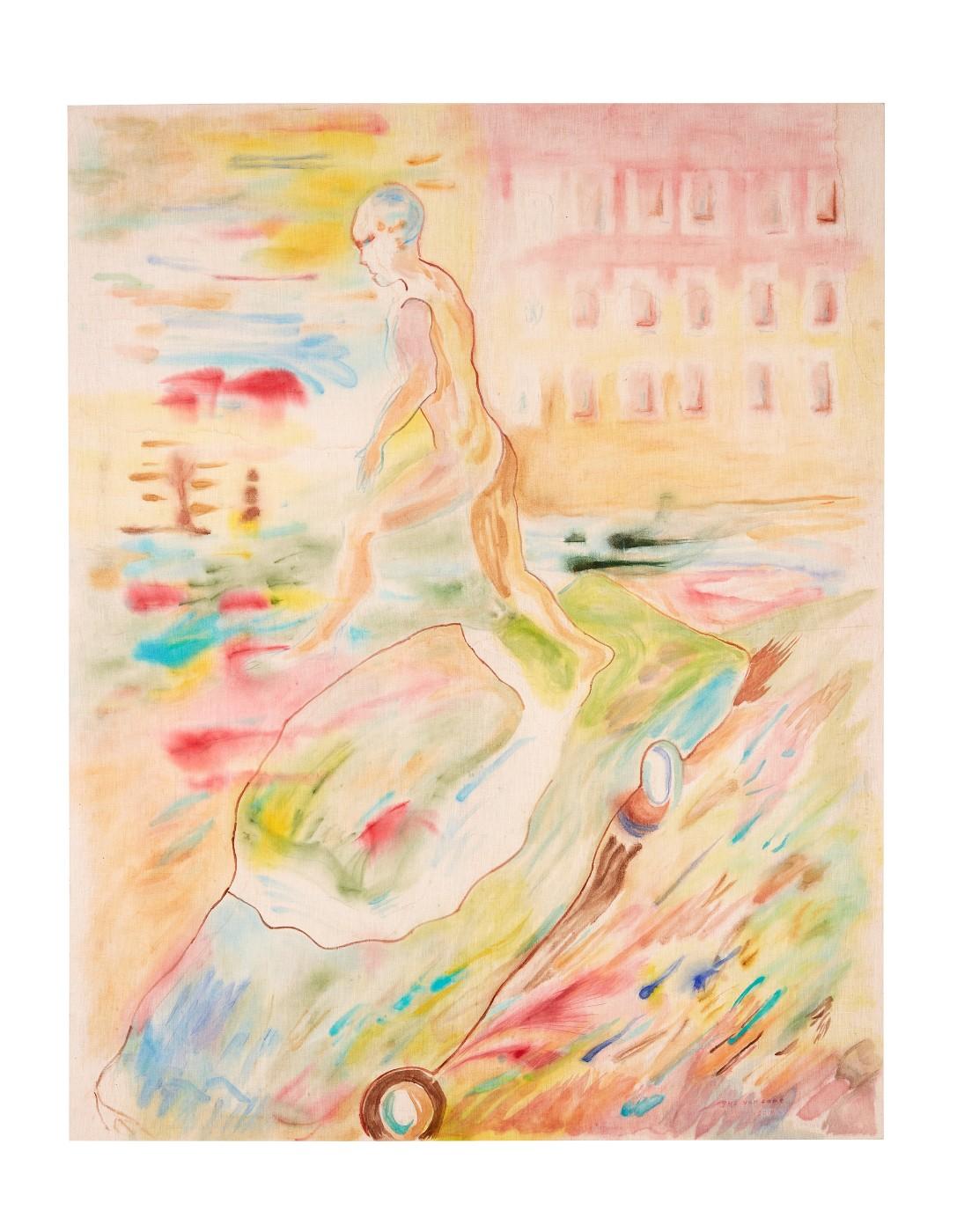

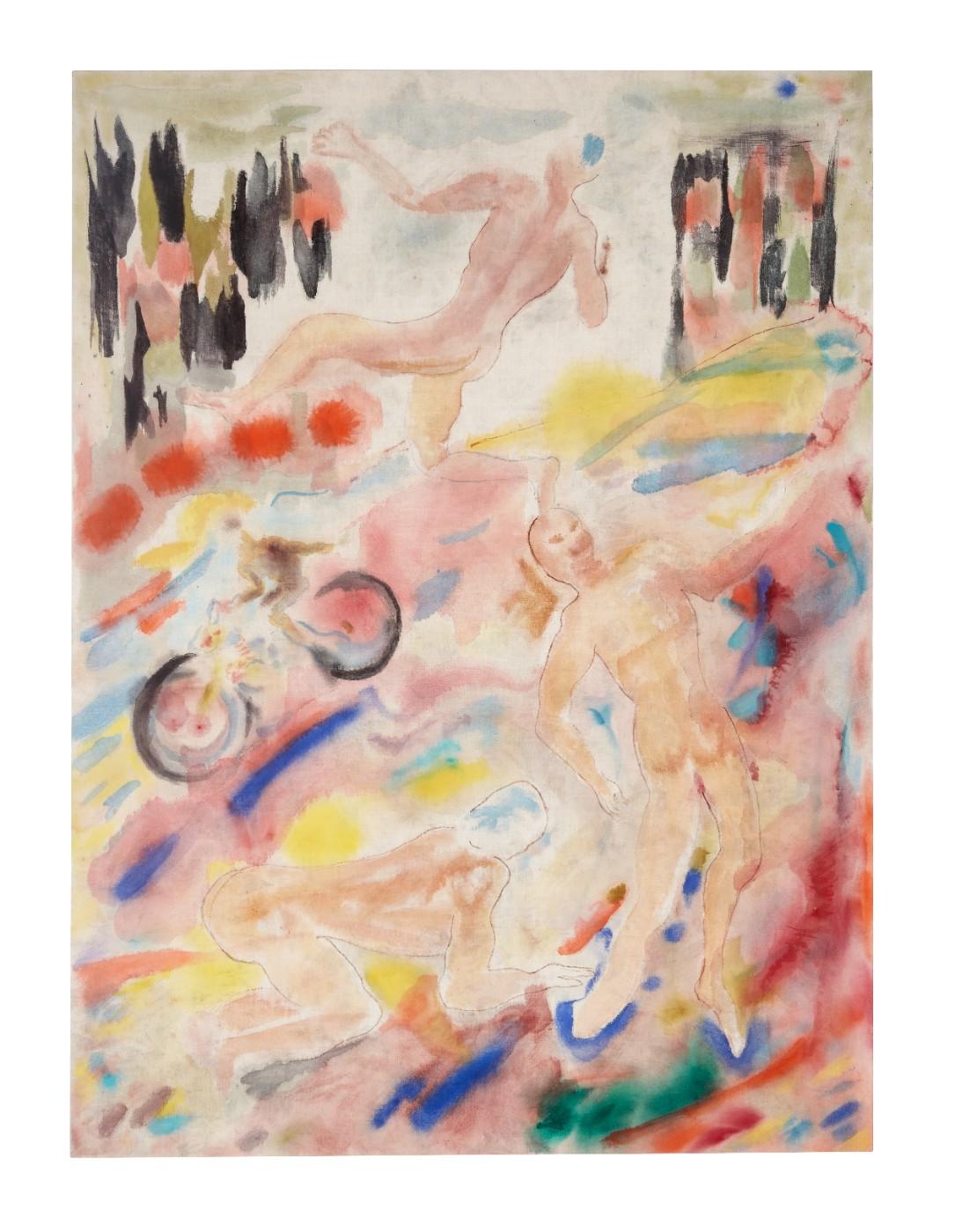

For decades, Van Sant has been frozen into film. But he has quietly been keeping up his practice, the evidence of which has been on exhibit in venus like Le Case d'Arte in Milan, the Musée de l'Elysée in Lausanne and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon in Eugene, among others, as well as a show with James Franco at Gagosian in Beverly Hills in 2011. His new solo show, Recent Paintings, Hollywood Boulevard, is at Vito Schnabel Gallery in Greenwich Village through Nov. 1, a series of nine large-scale figurative watercolors on linen.