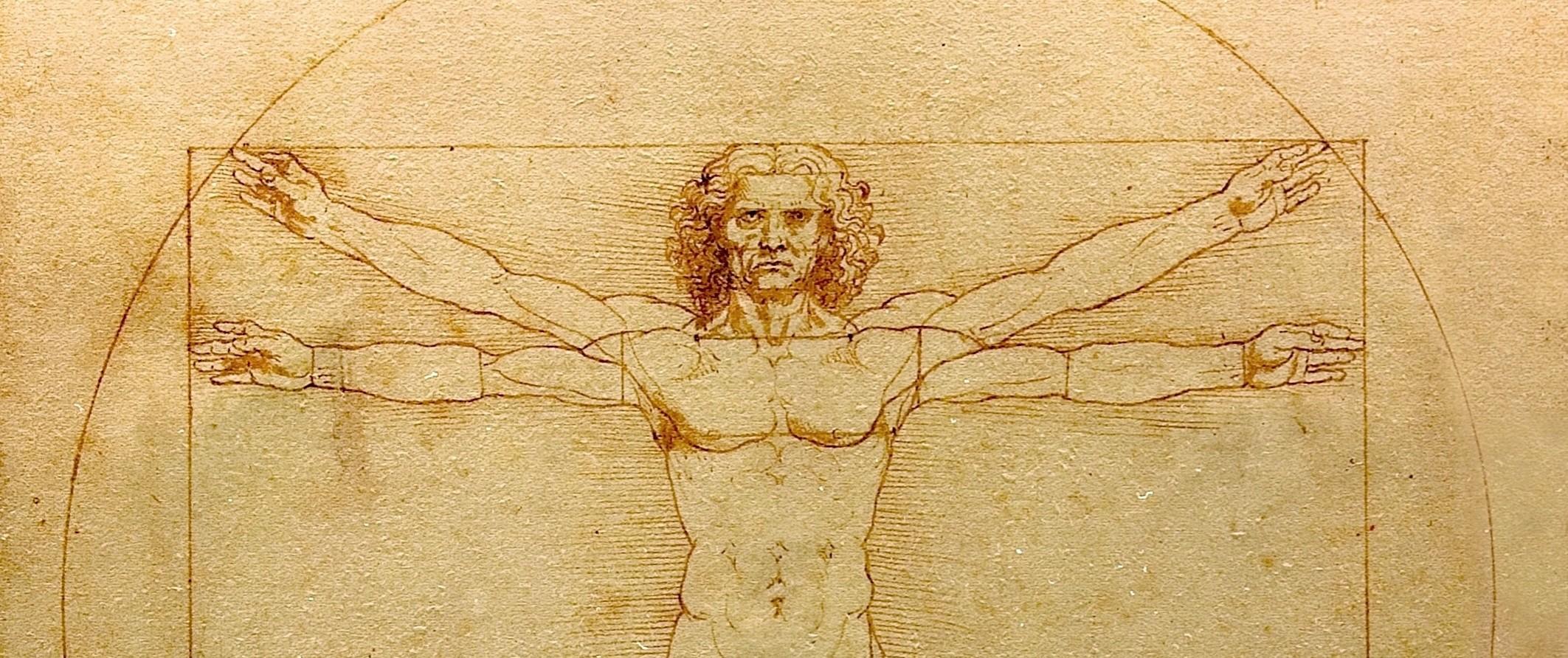

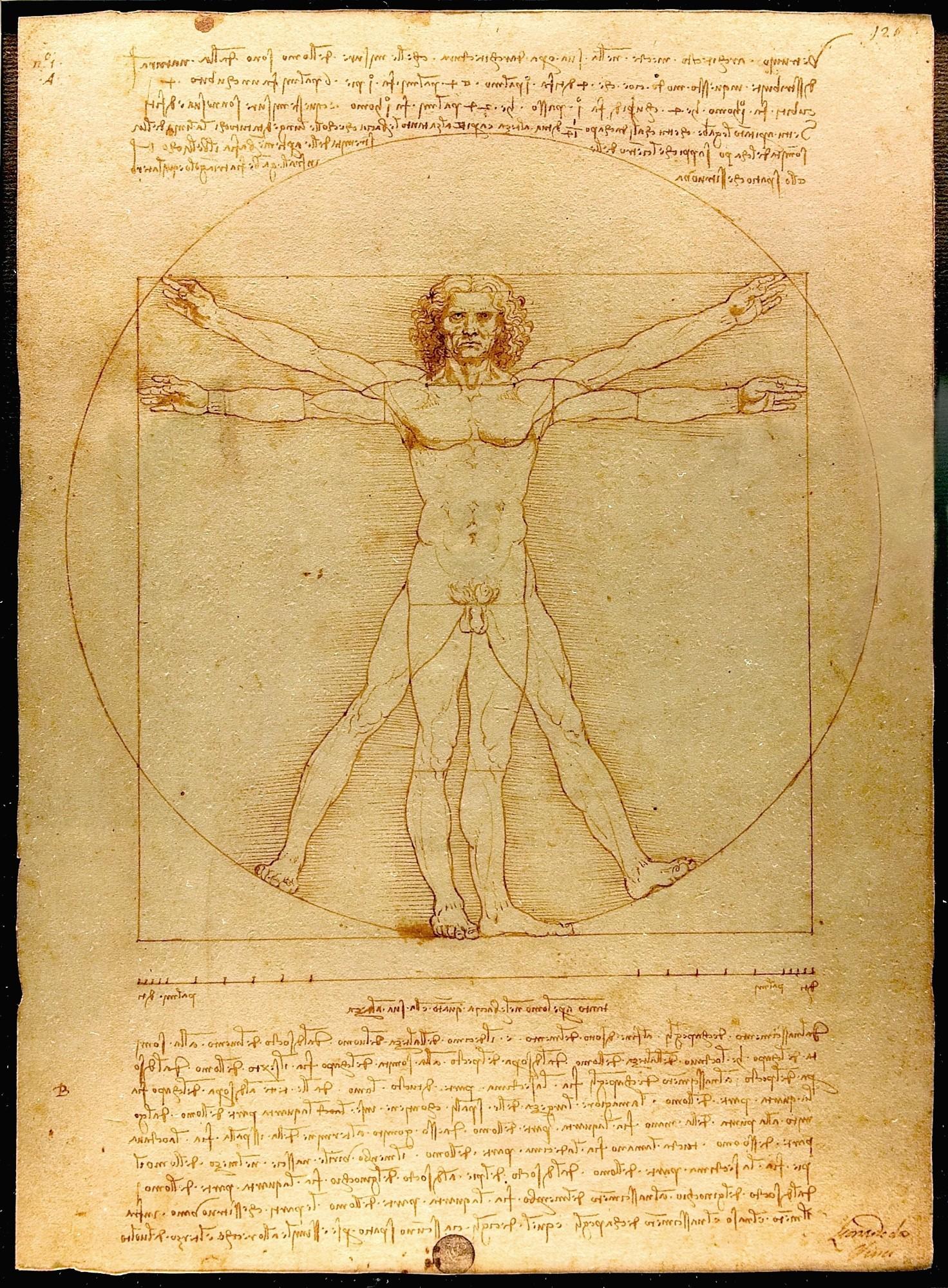

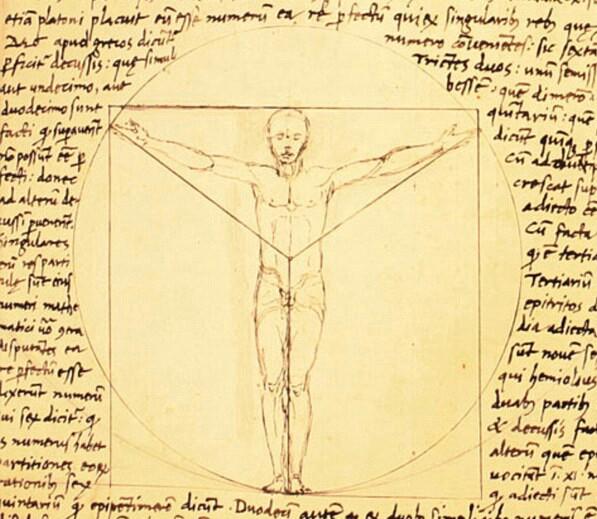

Smithsonian Magazine reports that others had attempted the drawing earlier in the 15th century, and notes that the shapes drawn around the man have important significance. Beyond trying to measure the proportions of the human form, “ancient thinkers had long invested the circle and square with symbolic powers.” For these thinkers, circular shapes were linked to the “cosmic and the divine,” while the square represented what was “earth and secular.”

By imposing a human form inside these shapes, scholars were not just noting bodily proportions; they were also showing how humans fit in both worlds and could actually serve as a way to study the perfection of the universe. By doing so, Vitruvius and other architectural scholars believed they could carry over this perfection into the realm of architecture.

This principle of humans serving as a link between the earth and the divine seems to be one that Da Vinci believed, too. As quoted in the book Da Vinci’s Ghost by Toby Lester, the artist wrote in 1492, “By the ancients man was termed a lesser world, and certainly the use of this name is well bestowed, because…his body is an analogue for the world.”

However, rather than copy Vitruvius’ findings himself, Da Vinci notes in image’s accompanying backwards text that his Vitruvian Man features adjusted positioning of Virtruvius’ circle and square, as well as some of the proportions and positions of the man’s limbs based on his own studies of the human form.