This kind of copying eventually led to copyright laws. Although Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) was the first artist we know of who attempted to pursue legal action in reaction to what would now be seen as copyright infringement, laws to protect against such an occurrence were not passed until much later.

Finally, in the early eighteenth century, what was colloquially referred to as Hogarth’s Law (a la the painter William Hogarth (1697-1764)) was enacted and artists finally received protection against the blatant recreation and selling of their work.

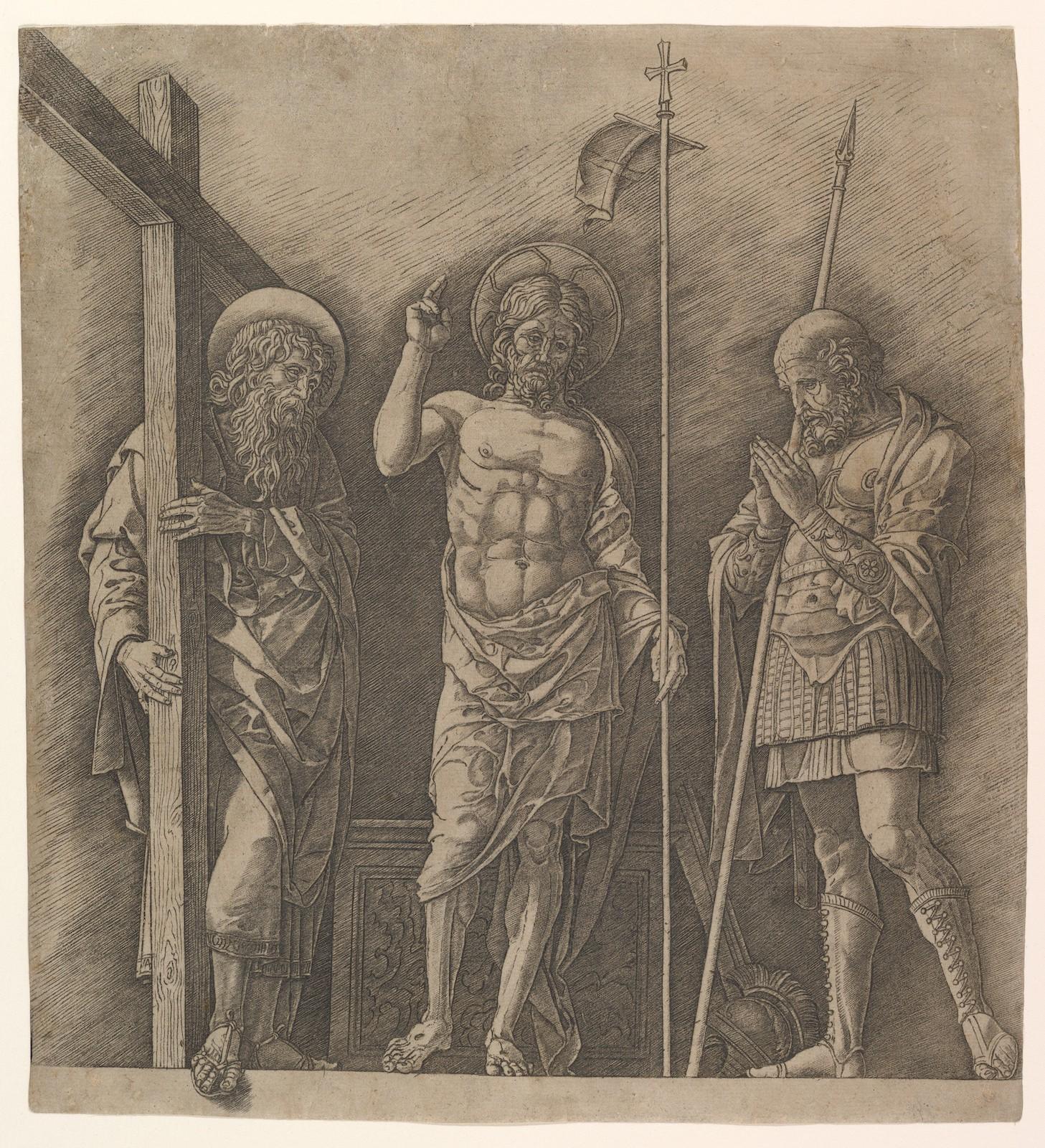

In addition to forgery and educationally-motivated copying, another mode of copying runs quite prominently through the course of art history. Copying as a form of homage was and still is a popular practice conducted by great artists.

Though often misunderstood by individuals on the peripheries and outside of the art world, this type of copying is typically achieved via the adoption of small details from another artwork. Much like the contemporary practice of sampling in rap music, the practice can be seen as a manner of personal innovation and a way to show respect to one’s predecessors rather than a copout.

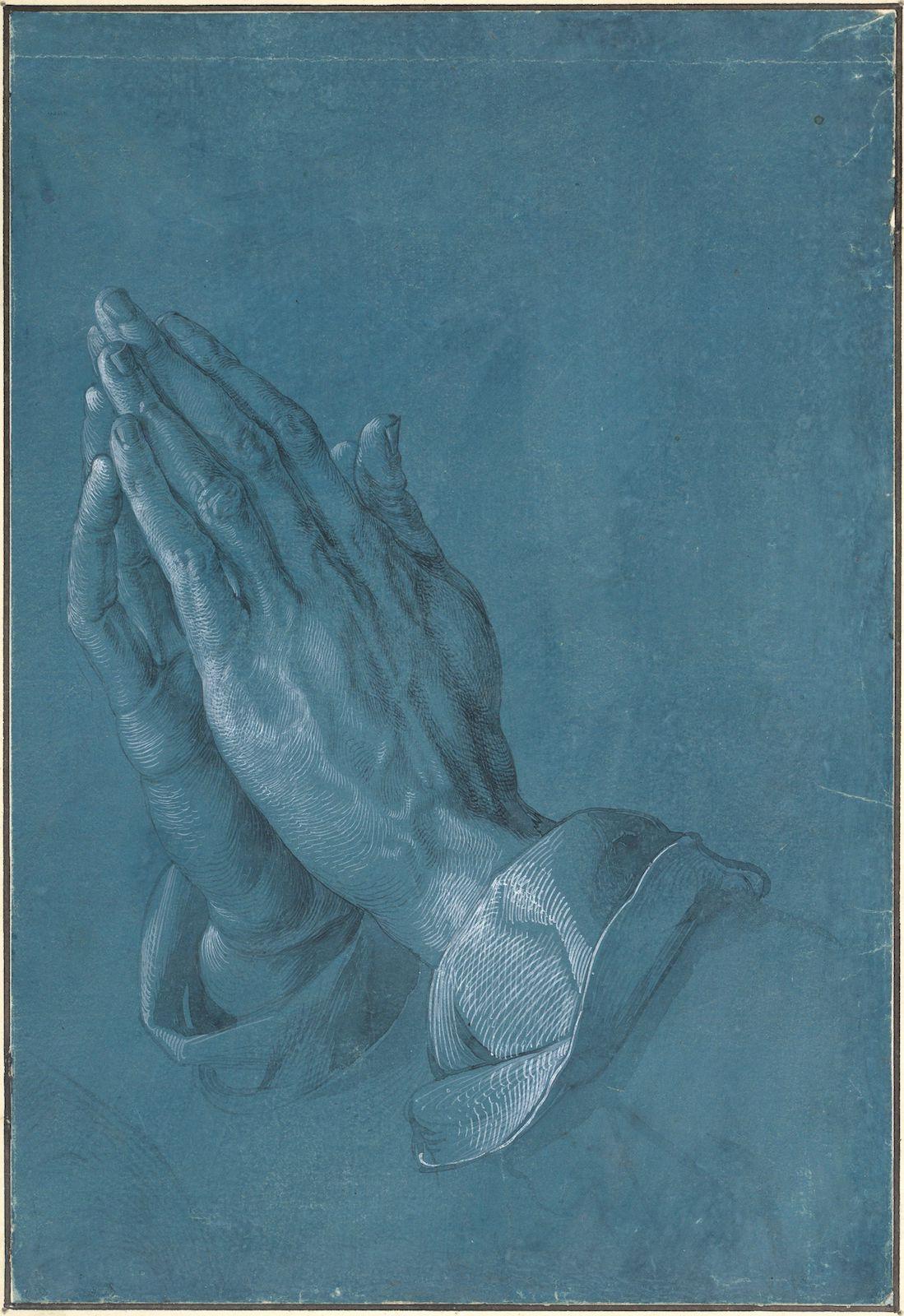

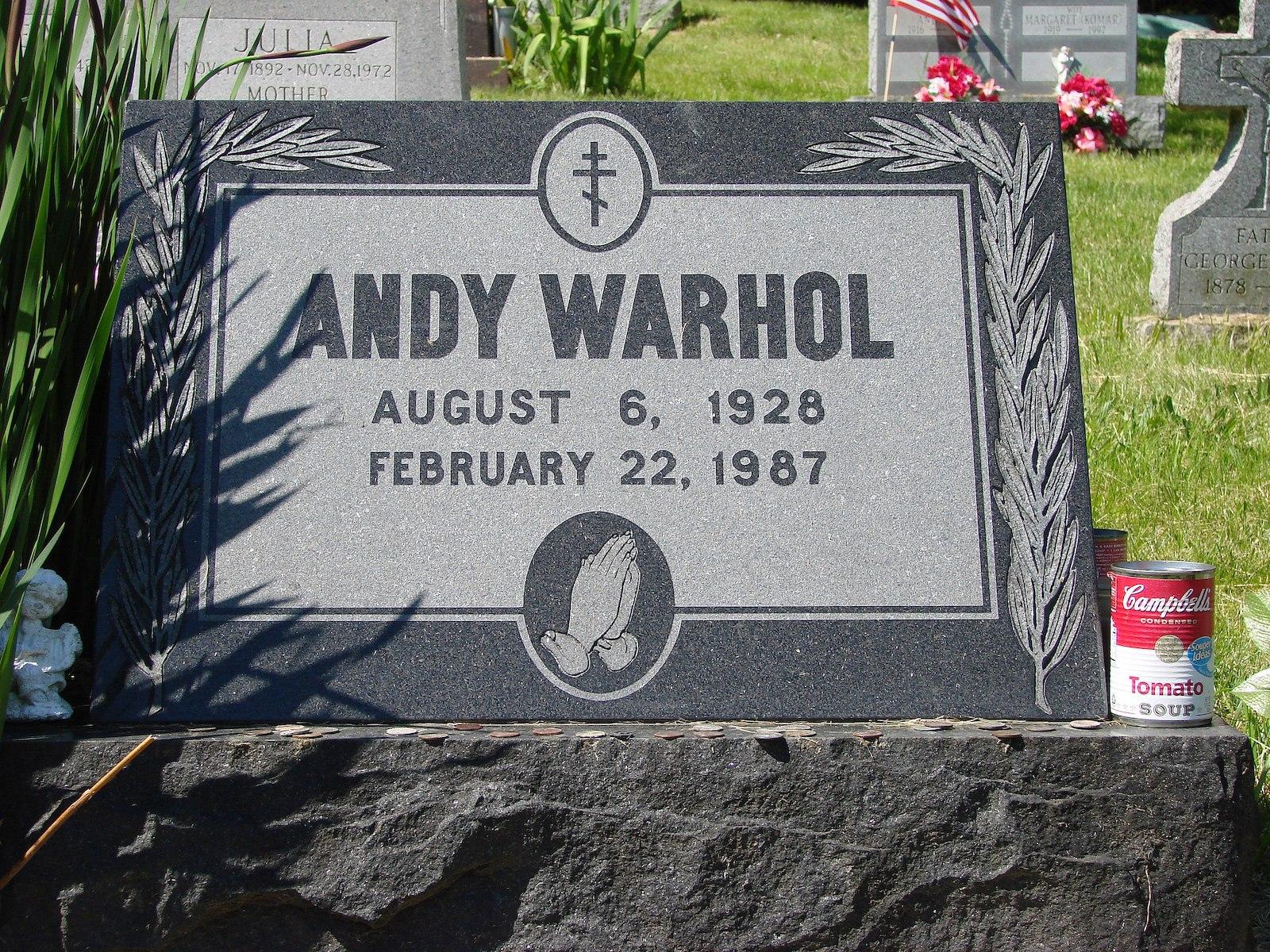

Dürer’s iconic drawing Praying Hands (1508) is a great case study for the nuance and importance of all three modes of copying. As previously mentioned, Dürer was somewhat of a pioneer within the field of copyright. Ironically, this particular drawing of his has been coopted and recycled so often that many now see it as rather kitschy.