However, due to the incompetence and irresponsibility of the captain, Hugues Duroys de Chaumareys, the Medusa drifted away from its travel companions and, ignoring all signs of warning from the other ships, it sailed until it ran aground upon the Arguin bank. The banks were a well-known and dangerous area off the coast of Mauritania, which the captain had known about and been informed that the ship should avoid.

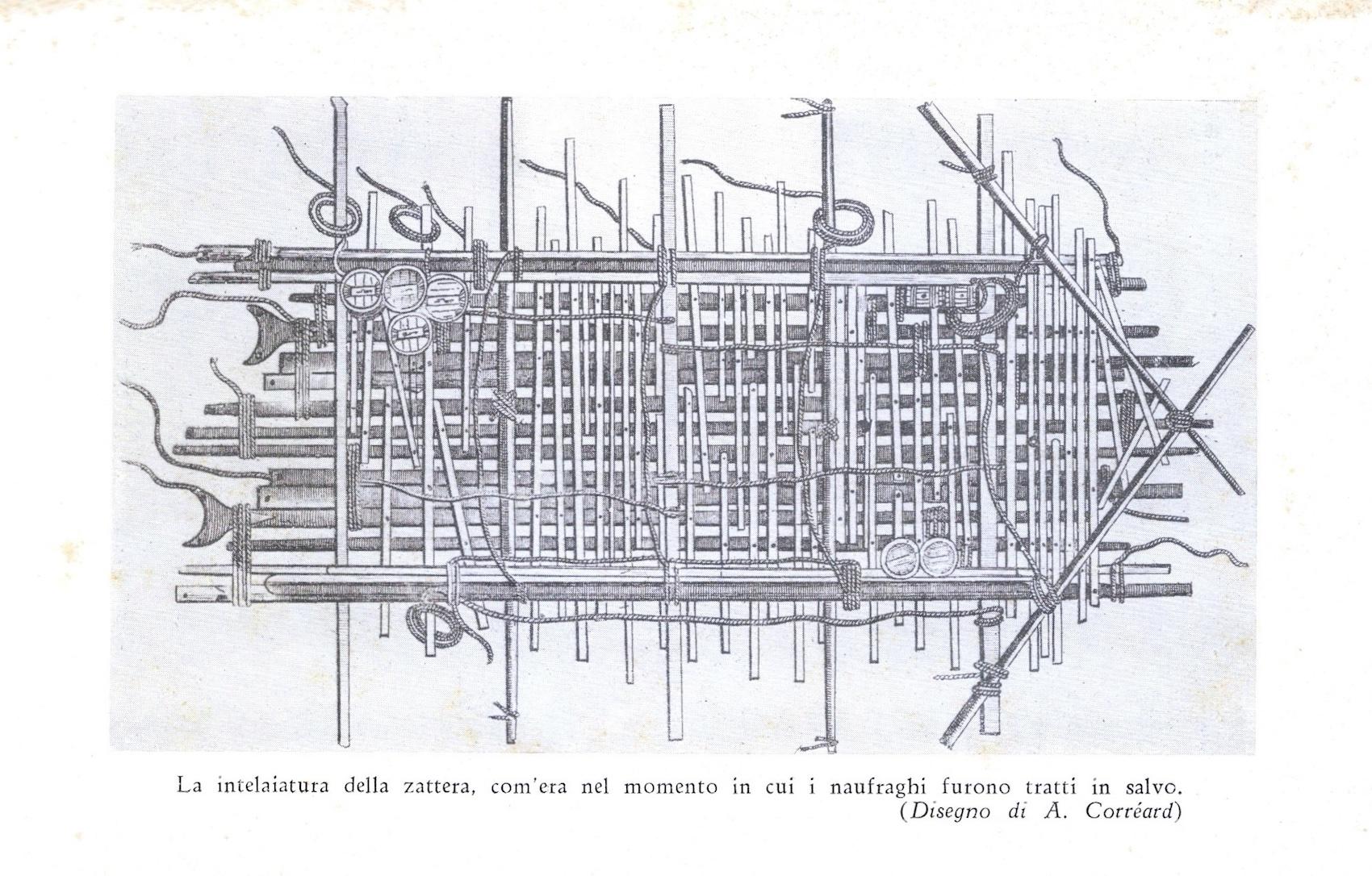

After many attempts to dislodge the frigate, being far from land and completely isolated, it was decided that the only chance for survival was to abandon the ship and try to reach the shore with the lifeboats– of which there weren’t enough for all passengers. As such, the ship was partially dismantled and from the recovered material, a raft was built and 152 people were placed, most of whom were civilian passengers.

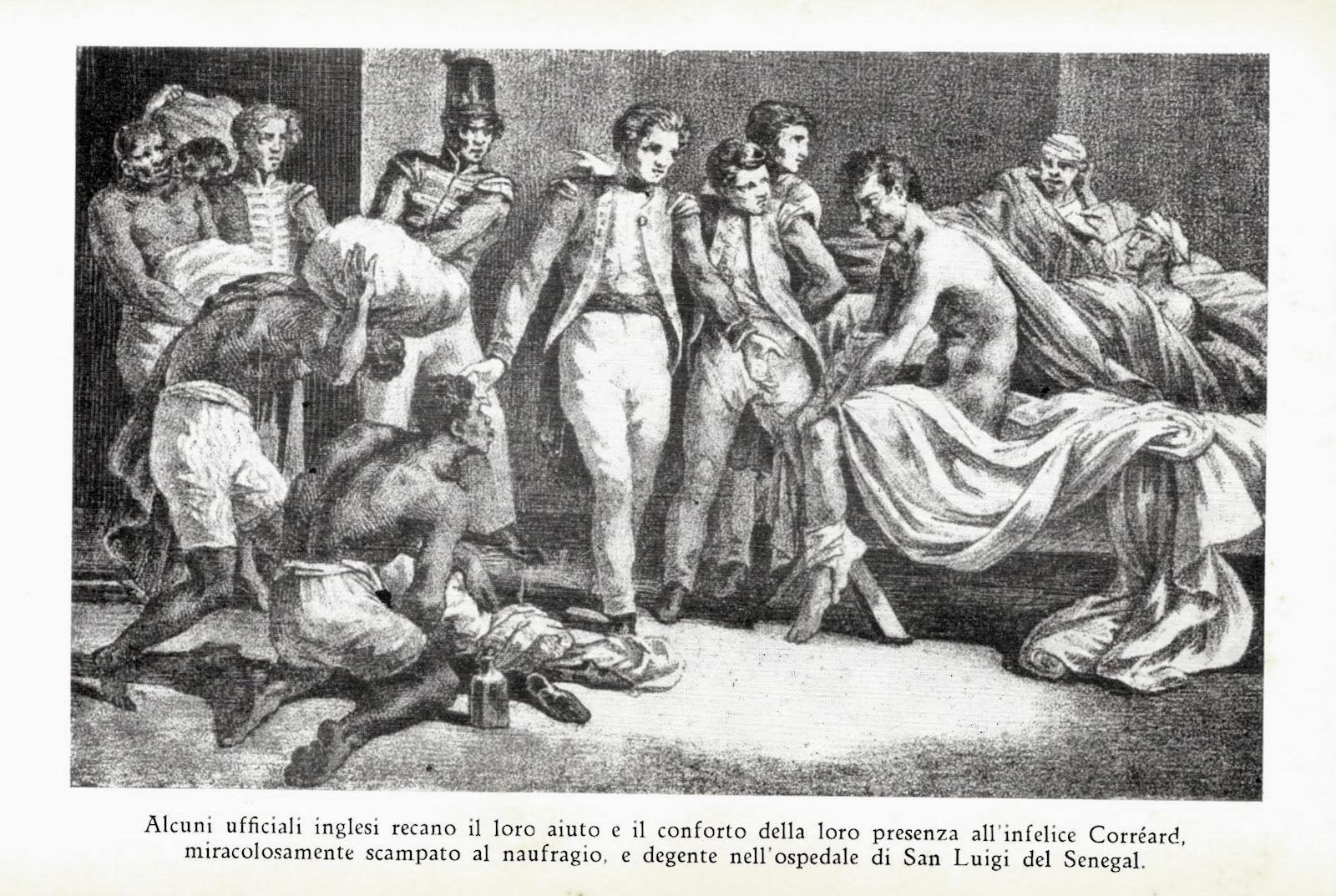

Meanwhile, the lifeboats ended up accommodating only high-ranking officers, the captain, the governor, his family, and others loyal to them. Even with these individuals aboard, there was still room for others.

The intention of the marooned group was to tow the raft by some of the lifeboats, but it was not long before those heartless people intentionally let go of the ropes, condemning the 152 passengers to a slow and horrible death. Crammed onto that overcrowded and precarious structure, the passengers possessed only two small barrels of water, six barrels of wine, and 25 pounds of salty, water-drenched food.