They found their way into international markets and have consistently won design and quality awards throughout the years. Four decades of invasions and civil strife culminating in the United States backed War on Terror against the Taliban have driven many Afghan refugees into neighboring Pakistan, taking their carpet making skills with them to a country where some of the worst violations of child and forced labor have occurred.

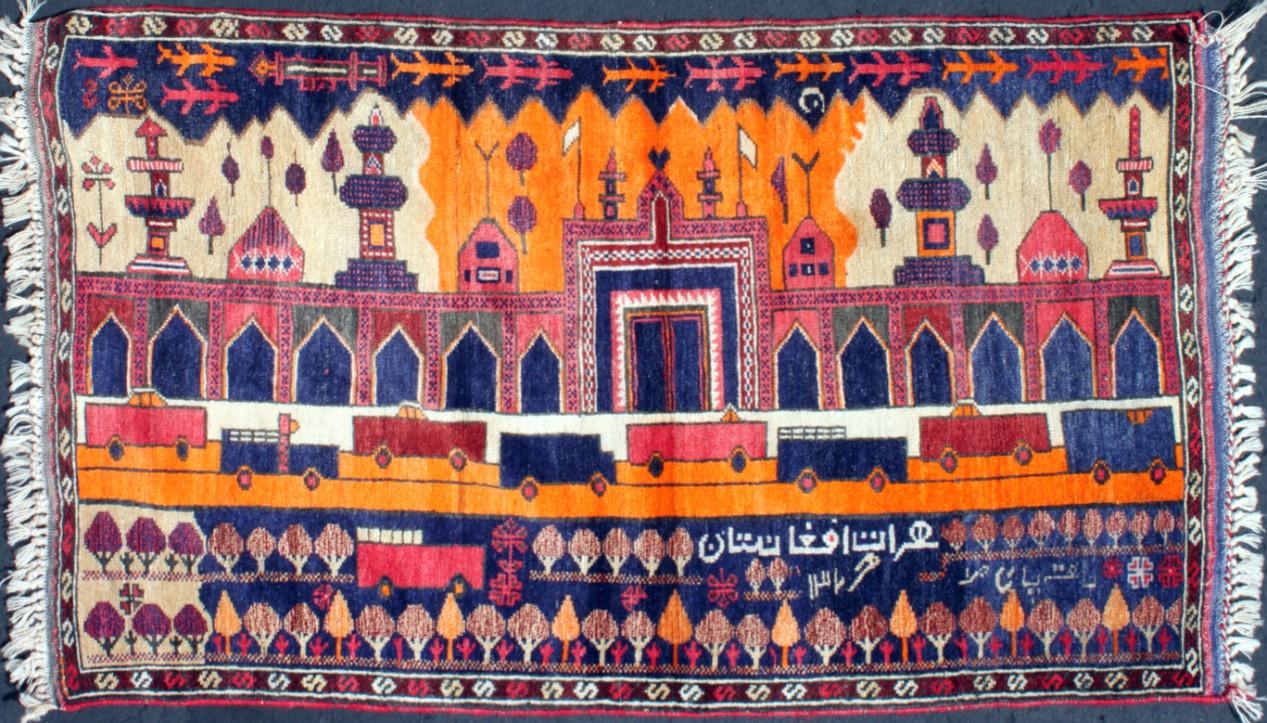

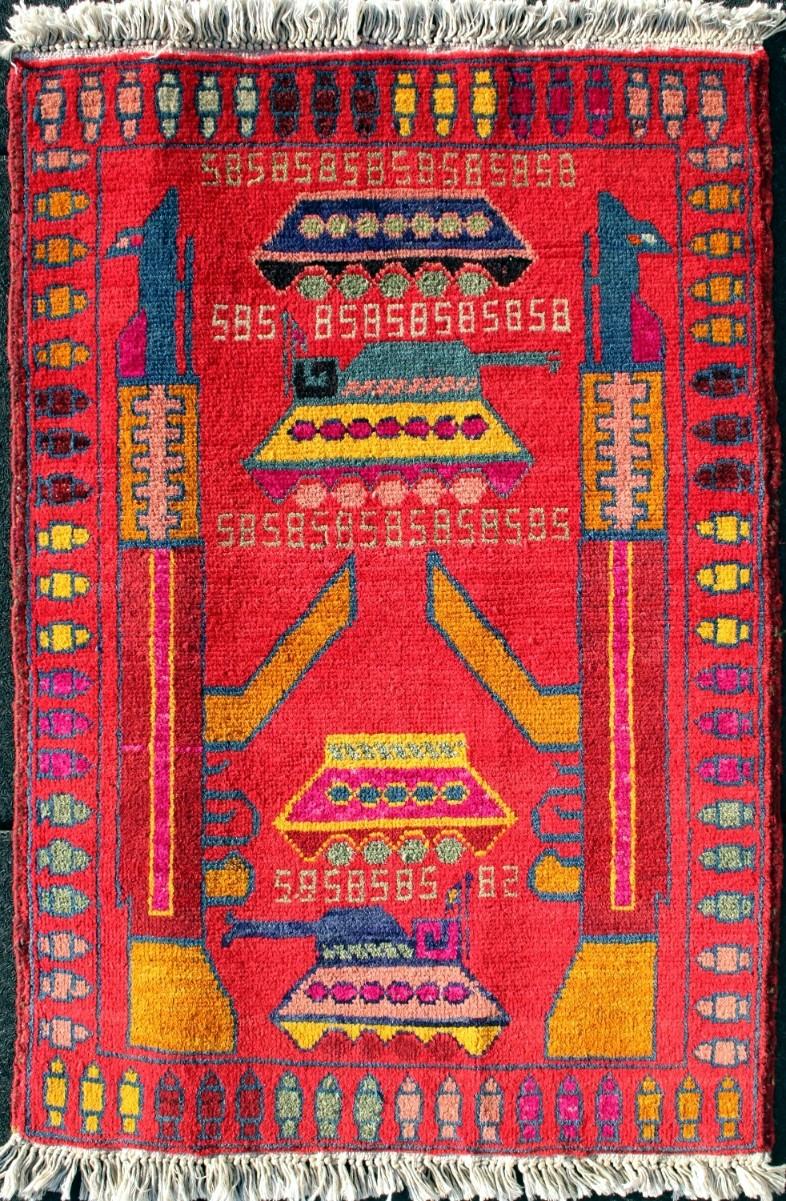

Afghan rug depicting the Herat Mosque

The ancient art of carpet weaving has been the cultural heart and soul of Afghanistan for centuries. The current perception that the country has always been a war-torn backwater ignores the facts, including a rich history of craftsmanship as evidenced by the synonymous association of quality with an Afghan carpet.

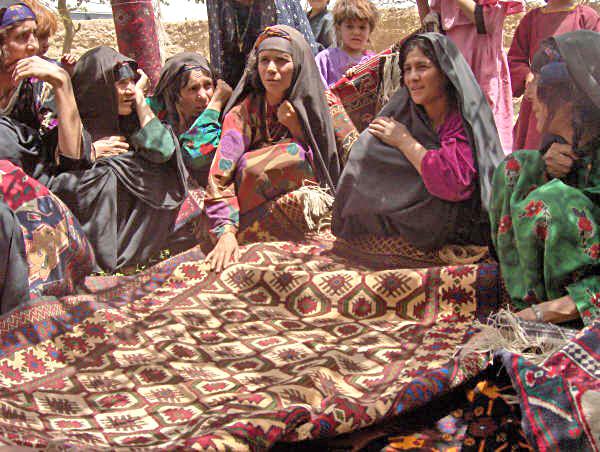

Prior to the Soviet invasion in 1979, Afghanistan was a rural, relatively peaceful society with a large, nomadic tribal population. Men herded sheep, providing food and high-quality wool that was used in the making of carpets, which were hand-woven largely by women and children. Unique patterns and design elements became associated with certain villages or communities, such as the Turkmen in northern and western Afghanistan, the Adraskan in Herat Province and the Baloch in the southwest of the country. The best examples are considered works of art as well as craft featuring rich, earth-sourced colors and brilliant red tones.

Afghan rug weavers

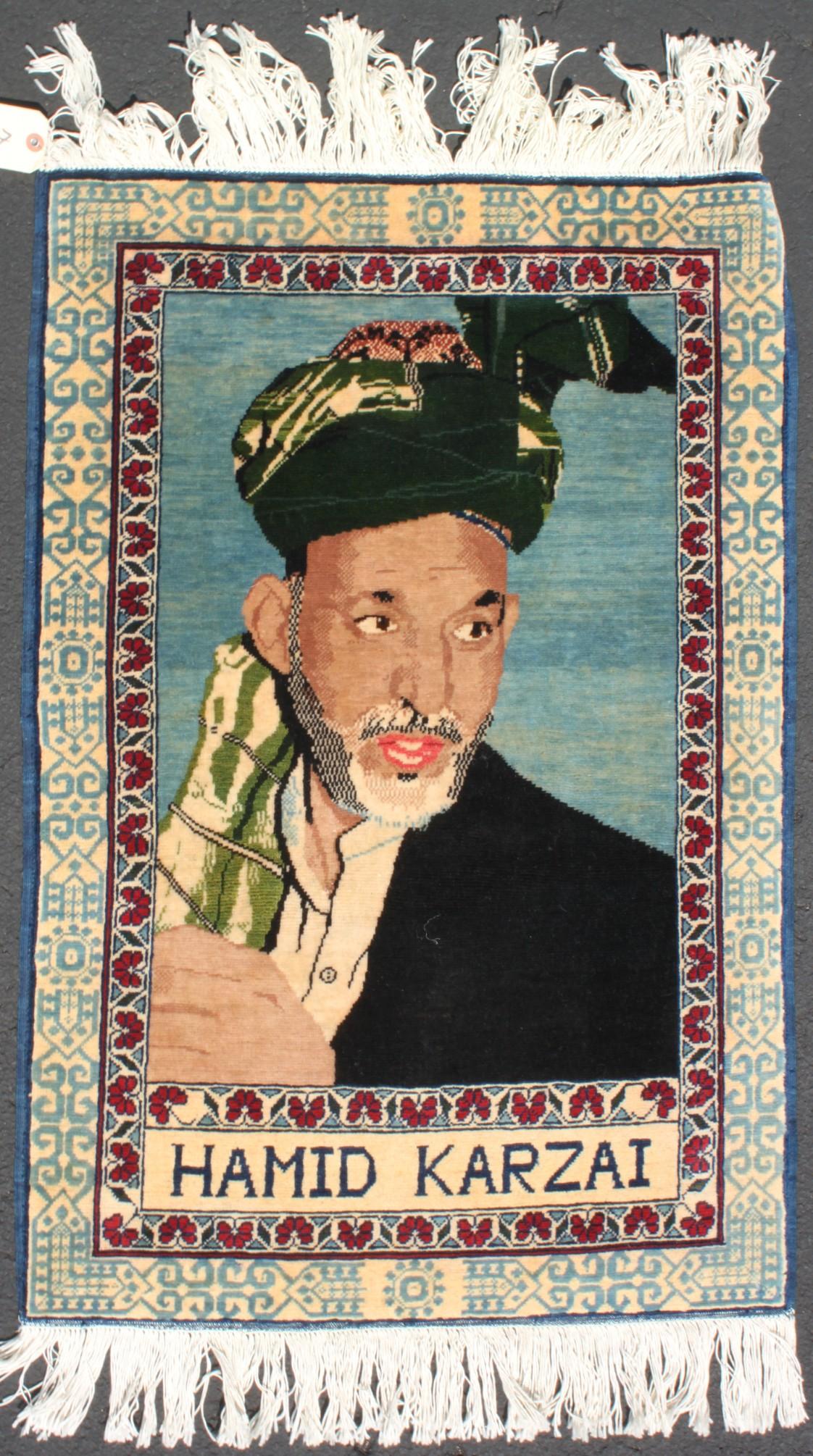

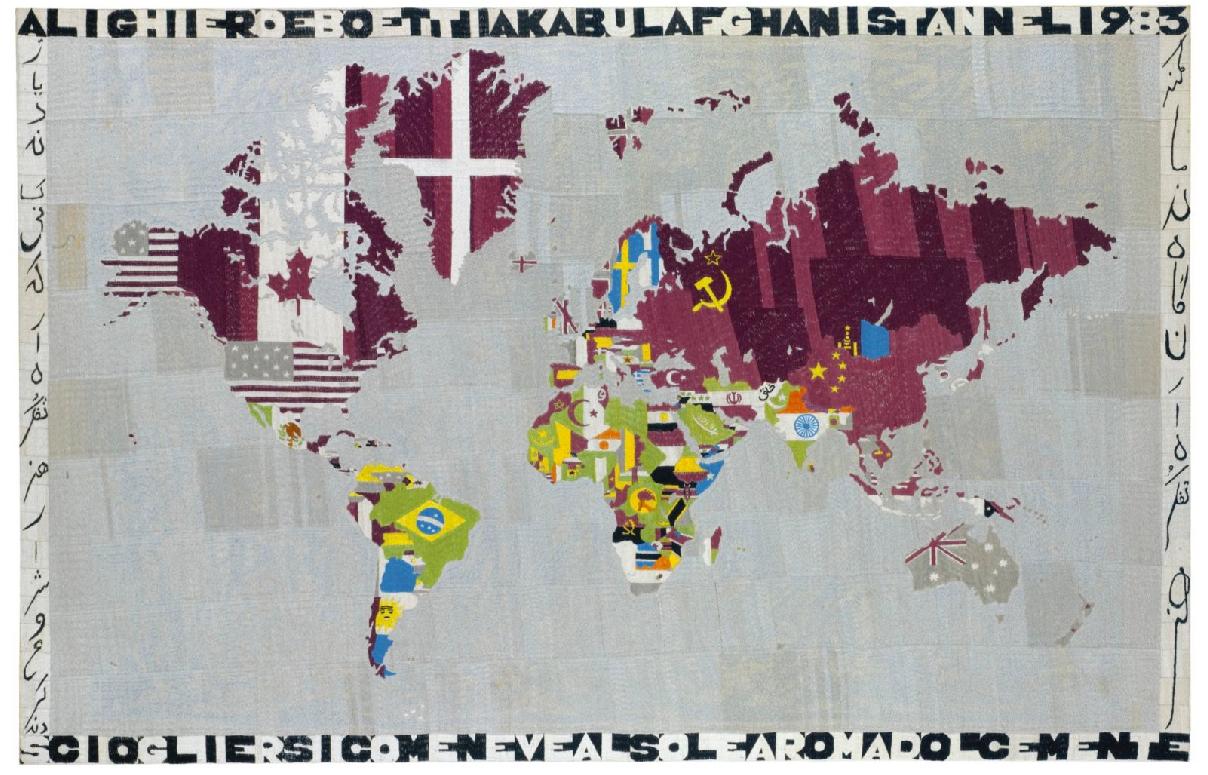

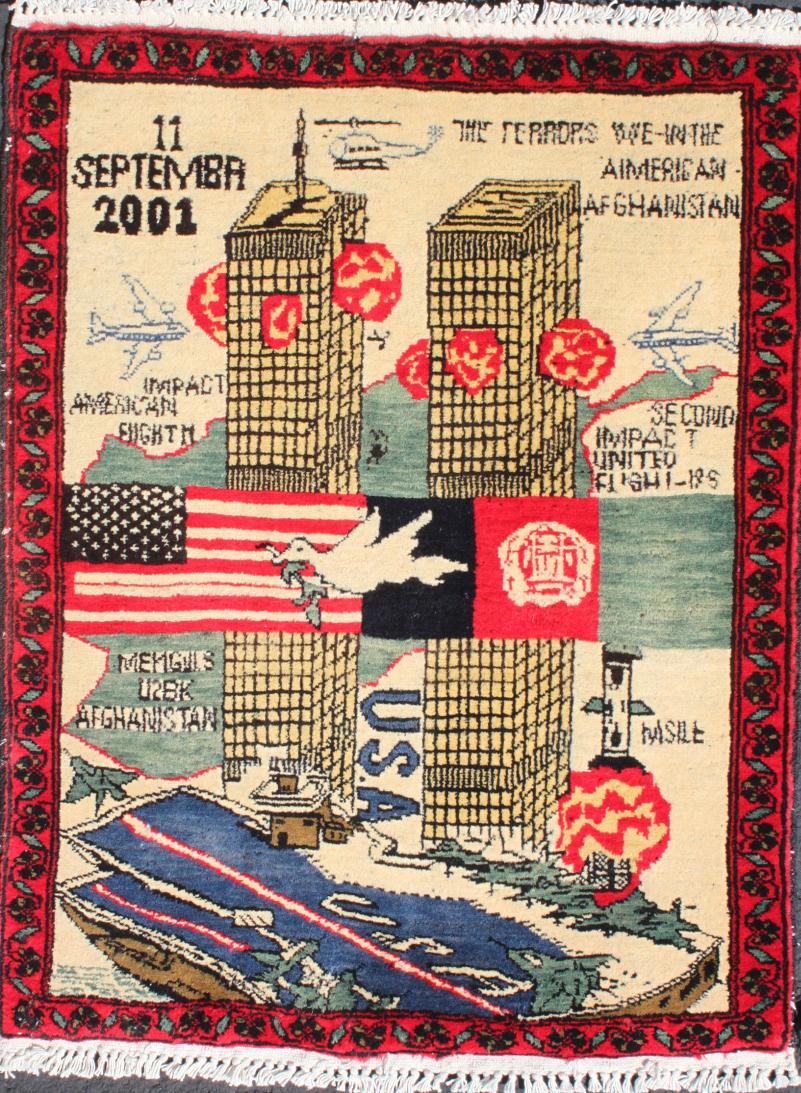

Carpet designs have long reflected their lives, including war, which has been a subject for Afghan weavers since 1971, before the Soviet Invasion, introduced by the Italian conceptual artist Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994). Boetti began commissioning Afghan women to produce textiles based on maps sourced from newspaper accounts illustrating the 1967 Arab-Israeli Six-Day War. From 1979 onward until today Afghan weavers have embraced imagery torn from newspaper headlines producing highly stylized woven portraits of political leaders, Kalashnikovs, tanks, flags, maps, munitions, soldiers, fighter jets, drones and architectural landmarks often integrated with traditional border designs and nature-inspired forms.

Alighiero Boetti, Mappa, 1983.

Kevin Sudeith has become the world’s foremost collector and authority on the origins of Afghan war rugs. Trained as an artist at the San Francisco Art Institute and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, he has an eye for unique design anomalies. It was in the early 1990s when Sudeith first noticed images of Soviet weapons mixed in with traditional designs and ancient patterns. He says, “the first rug that I bought was a red rug that had four Kalashnikovs on it, on the sides and then a mix of tanks and helicopters in the middle.”

In 1998 he founded Warrug, Inc., a platform for information as well as a conduit for sales of these carpets that are still mostly woven by women and produced collectively by groups with extended family ties. Fifty-nine fine examples of war rugs from Sudeith’s collection are shown in WARP: War Rugs of Afghanistan, a touring exhibition organized by the Gund Gallery at Kenyon College currently shown through May 8 at the University of Vermont’s Fleming Museum of Art. These carpets trace the trajectory of various conflicts through imagery groupings of maps, munitions, portraits, prayer rugs, architecture and cities, and finally, perhaps the most jarring, the World Trade Center and 9/11. One smaller example (24x32 inches) from 2002 is packed with almost cartoon-like renderings of planes crashing into the Twin Towers above a U.S. aircraft carrier along with both Afghan and U.S. flags and a dove of peace.

There is a visceral response to remnants of contemporary warfare when incorporated with this ancient craft. Demand is high among collectors. And while urbanization and commercialization have already put an end to unique, hand-woven carpets in much of the world, Afghanistan continues to be a primary producer thanks in part to collectors like Sudeith who buy directly from the Afghan community and NGOs like Turquoise Mountain, a group working to restore Afghanistan’s ancient architecture and support the work of artisans who keep the country's traditional arts and culture alive.