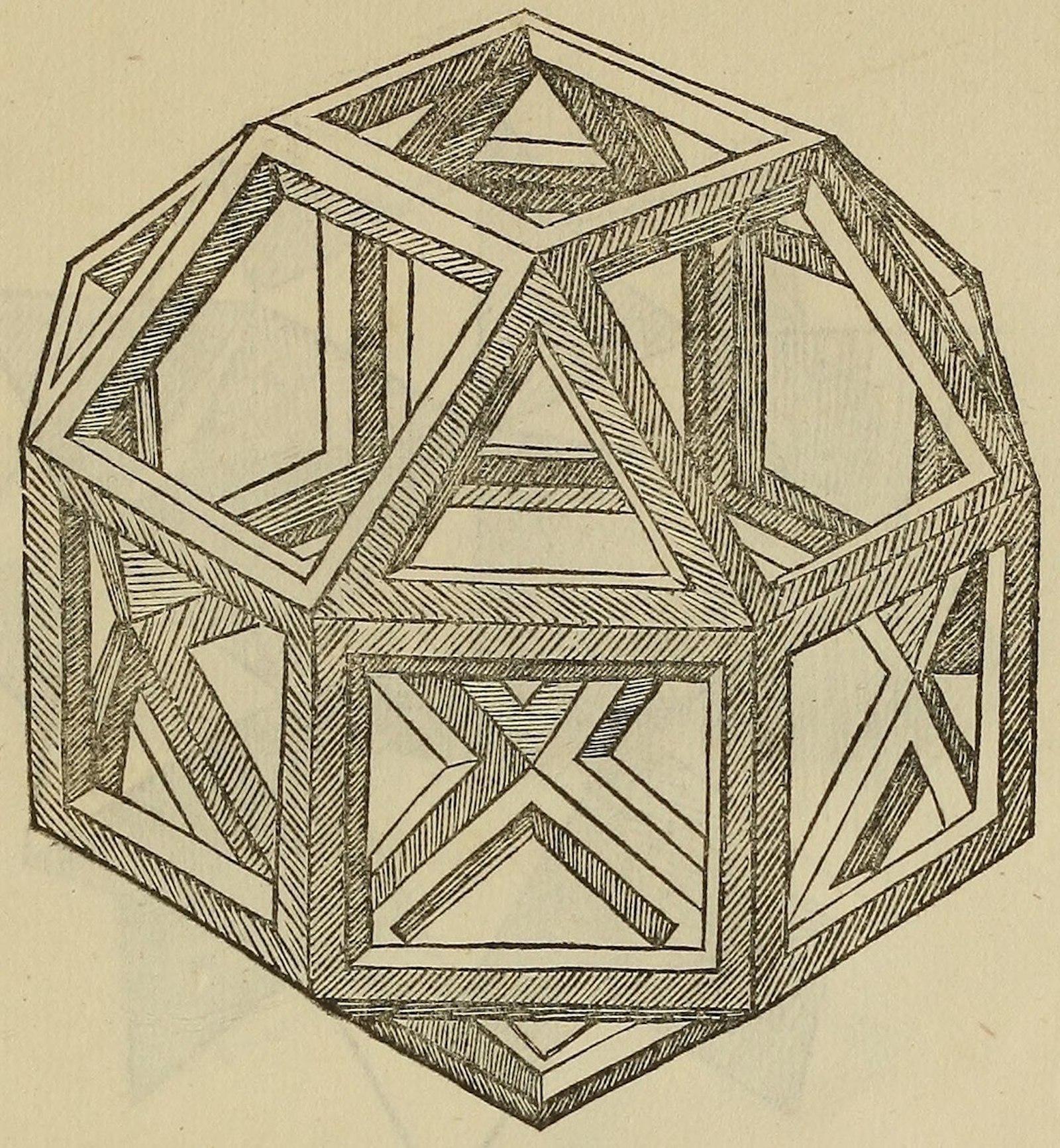

This is easiest to demonstrate with the golden spiral, which is often depicted and constructed within a rectangular frame. The ratio between this rectangle’s length and width is that of the golden ratio.

The spiral is built by portioning the original rectangle into two pieces—a square and rectangle of the same proportional width and length. The process is repeated and the spiral is applied via quarter-circles that run from corner to corner of the squares created.

The result is technically not a truly logarithmic or golden spiral but it is a close approximation. More importantly, this is the type of process artists have used to visualize and apply the divine proportion to their paintings throughout the centuries.