It should go without saying that signs, warnings, and barriers exist in museums and archaeological parks for a multitude of reasons. In the case of many museum objects, glass cases, shields, and physical obstacles in front of paintings and statues exist in order to protect objects from further deterioration and damage from both intentional and accidental actions. The very air itself can cause antique paints to oxidize and fade when left in uncontrolled environments, making encased preservation necessary. The Mona Lisa, for instance, has recently been shown recolored by digital methods, demonstrating how deteriorated her paint has become over 500 years.

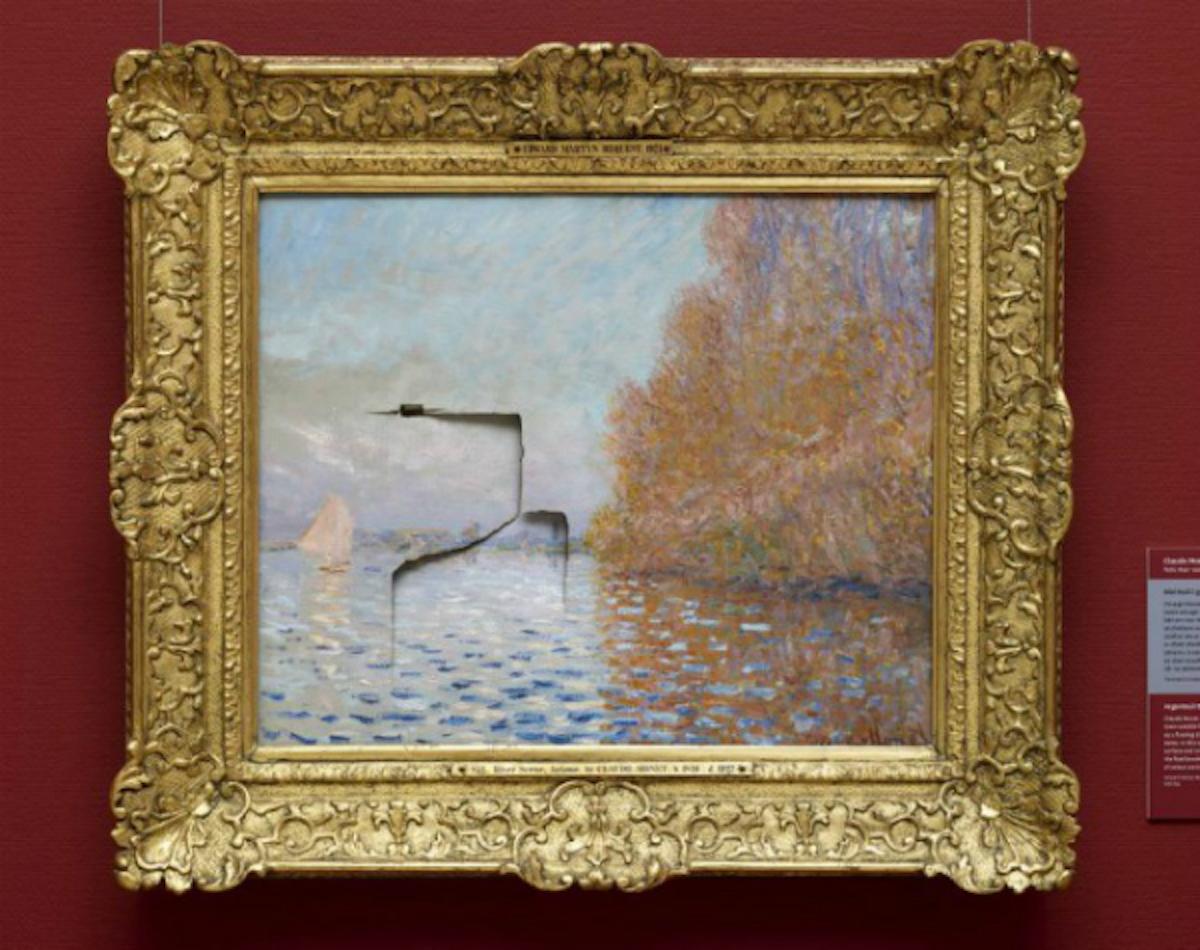

Many archaeological parks also employ the same tactics in their open-air settings. The Etruscan tombs in Tarquinia are sealed behind glass casings in order to protect the fragile frescoes painted over 2000 years ago. Such precautions are also in place to help prevent intentional or accidental damage, though plenty of instances have occurred where tourists have managed to cause severe injury to objects even with barriers in use. One young tourist in Taipei, Taiwan accidentally tripped and punched a Paolo Porpora oil painting valued at $1.5 million, and yet another tourist deliberately attacked a Monet painting in Dublin, Ireland, leaving three large rips in the 19th-century work worth $10 million.