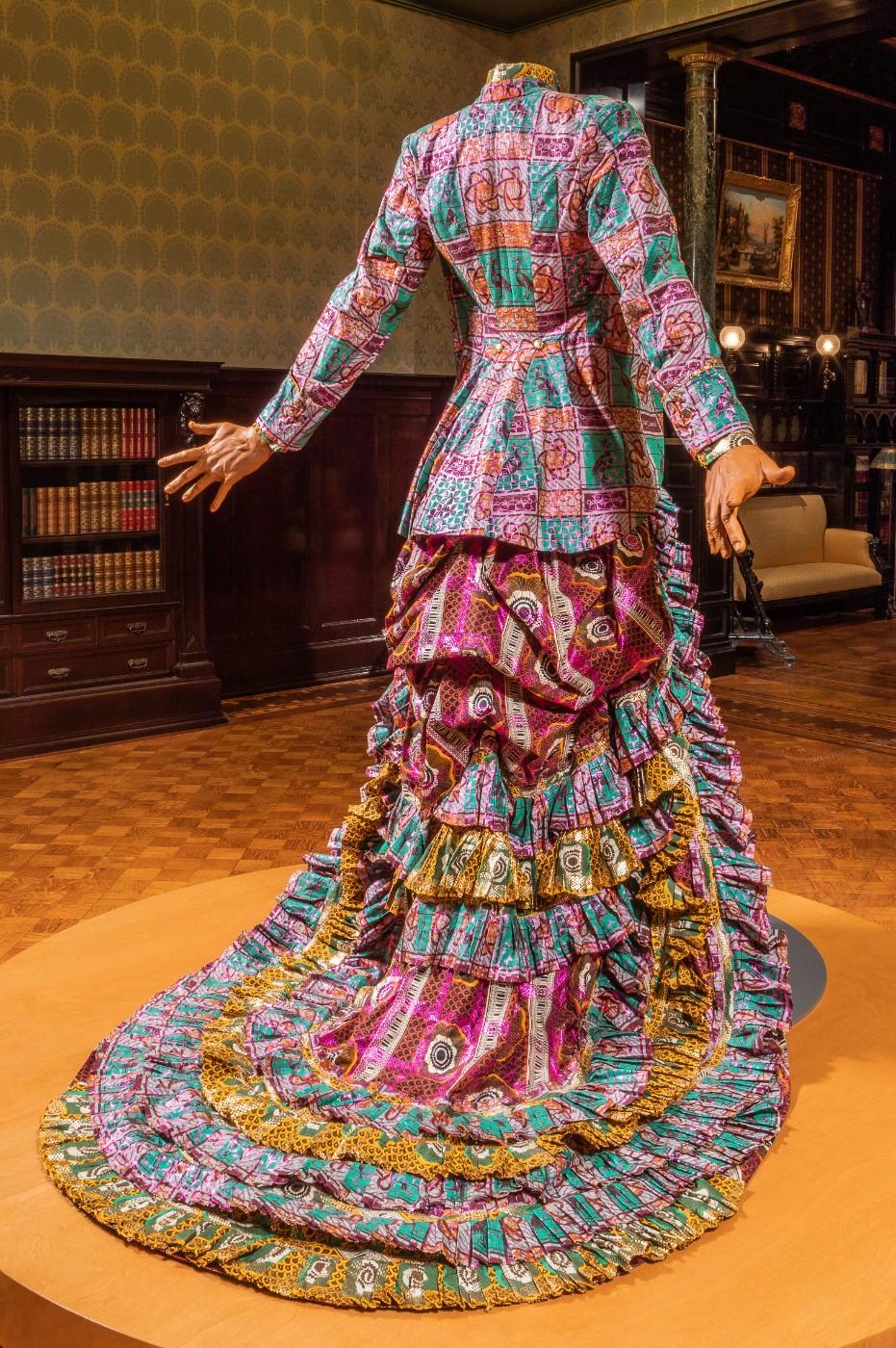

Each anonymous figure is not only headless—alluding to guillotined aristocrats of the French Revolution—but wears Victorian-style clothing in a signature textile in Shinobare’s work: batik fabric that has a convoluted history of reappropriation rooted in Dutch colonization. During the 19th-century, these patterned cloths known as Dutch wax fabrics were initially manufactured in the Netherlands and brought to Indonesia before they were sold in colonial African markets. Over time, they became global commodities and markers of African identity.

Shinobare, notably, works with European-made textiles from a London market; these “draw attention to the fabrics’ purported authenticity,” as historian Kirstin Purtich writes in the exhibition catalog. They are key to Shinobare’s practice, not only serving to remind us to read history beyond the superficial but also nodding to his own hybrid identity.

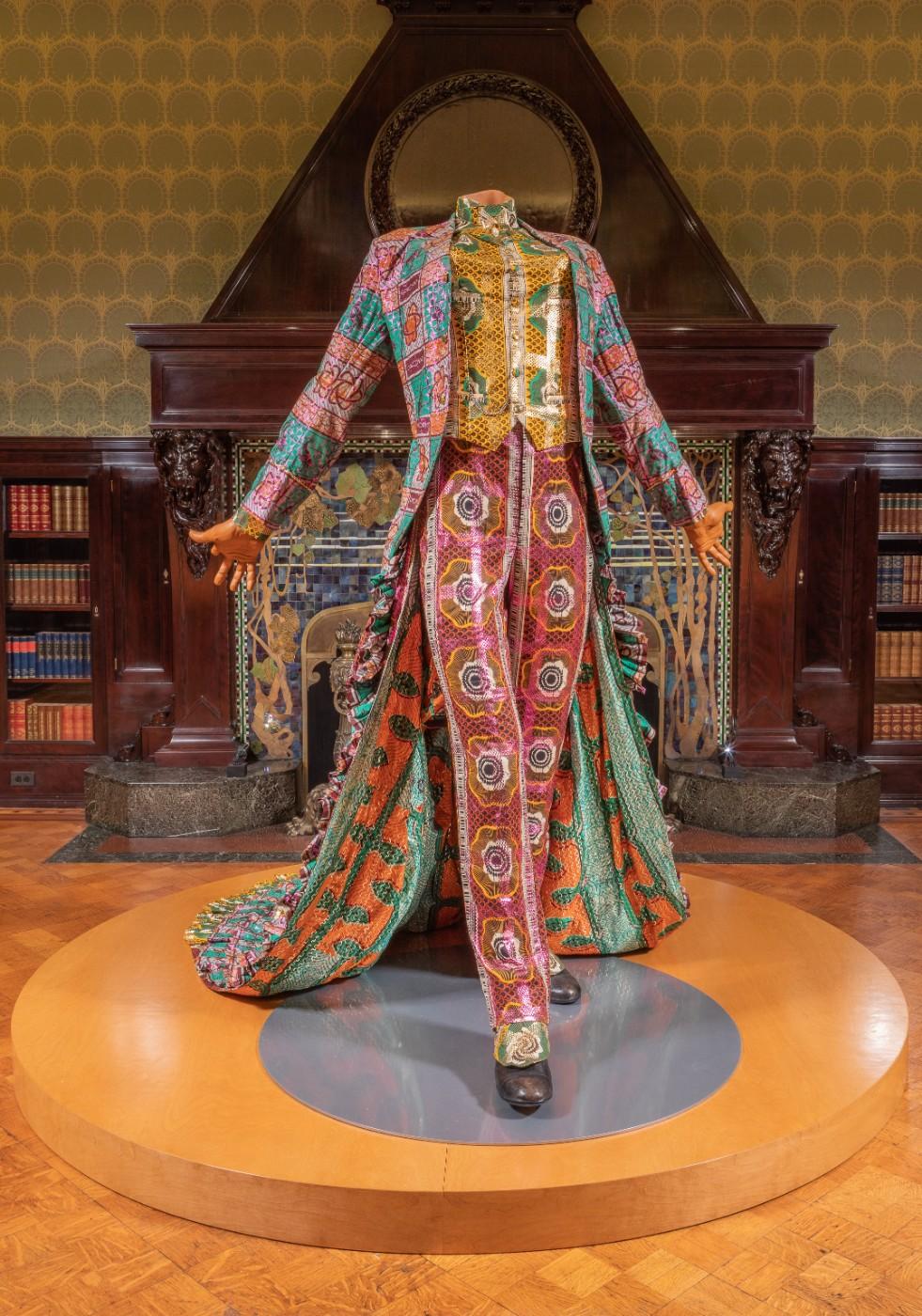

Beneath a magnificent glass dome in another room, a seven-foot-tall figure titled Big Boy (2002) shows off the textiles in a pair of trousers with an elaborate ruffled train. Appearing like a confident gentleman, the mannequin’s puffed-out chest has unexpected details: slight hints of breasts. “It deals with the Victorian dandy,” Richard Townsend, the Driehaus’ executive director, explains. “But it also speaks to contemporary concerns of gender roles and gender fluidity.”