So how does one launder money in the art world? The Globe and Mail reports that some of the cases are very straightforward. Let’s suppose someone has $10 million dollars on hand. They could buy a Picasso at an auction in, say, Geneva, and have the painting immediately moved to storage at a “freeport,” or a high-security storage space near the airport. The painting could be then anonymously sold without ever moving an inch, and the new buyer would have it retrieved from the same freeport. Suddenly, the original buyer, turned seller, has money from what is considered a legitimate business deal. The Economist estimated in 2013 that the Geneva freeport might hold $100 billion worth of U.S. art, sitting tucked away in a space that also functions as a tax haven.

Works of art have long been identified, and sometimes even romanticized, as ideal ways for racketeers to launder money. There’s a thread of logic here: the art world typically accommodates those that want to anonymously buy high-dollar paintings, and on top of that, the industry allows large cash deals. For those looking to launder money, it’s difficult to conjure up a more attractive set of circumstances than those.

There also seems to be plenty of instances where art has played a role in the act of money laundering. Consider that when the Mexican government passed a law in the early 2010s to require more information about buyers, and how much cash could be spent on a single piece of art, the market cratered, as sales dipped 70 percent in less than a year. Many believed that was because Mexican cartel rings had previously been the biggest buyers in the market.

The Geneva Freeport, a site where valuable artworks can be housed abroad in order to avoid import taxes

Jean-Michel Basquiat's Hannibal (1982), which was sold at Sotheby's after being seized by federal authorities.

Other cases are more complicated. Take, for example, a story about Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Hannibal painting, estimated to be worth $8 million. The work was smuggled into the U.S. by convicted Brazilian money launderer and former banker Edemar Cid Ferreira. According to The National Law Review, the painting had come to the U.S. “from Brazil, via the Netherlands, with false shipping invoices stating that the contents of the shipment were worth $100.” Presumably, Ferreira was on his way to the U.S. to sell the painting.

Then there is the case of international terrorism, where bands like ISIS have been noted for their laundering of cultural antiquities. Whereas much of the area that ISIS controlled has been taken over by government-backed forces, it is reported that the group still controls millions of dollars—and possibly hundreds of millions—thanks in large part to a robust antiquities trade.

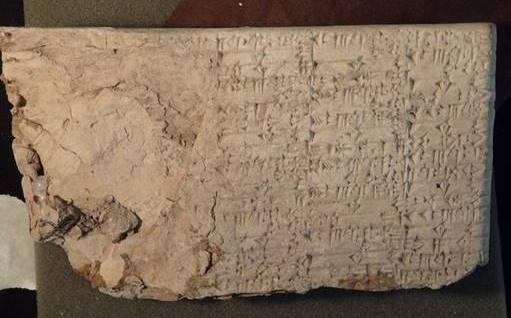

In 2017, the Wall Street Journal published a longform feature reporting how, exactly, ISIS turns these artifacts into revenue. The process begins with ISIS-affiliated jihadists overseeing local digging groups in Iraq in Syria. If and when an object of value is found, the digger sells it to ISIS officials at a discounted price. The goods are sold to independent middlemen who smuggle them out of the country, into border countries like Lebanon and Turkey. Eventually the goods find their way to warehouses in Europe where they await a Western buyer. This is essentially the process by which the president of Oklahoma City-based retail giant Hobby Lobby was buying Iraqi artifacts for the Museum of the Bible, and though it is impossible to say if the objects were of ISIS-related provenance, the lack of documentation and regulation in this uncertain world means anything is possible. Again, that makes it an ideal venue for money laundering.

A cuneiform tablet purchased for the Museum of the Bible, seized by the US Department of Justice

And yet, not everyone agrees money laundering in the art world is as prevalent as it’s purported to be. That discussion has picked up in the U.S. in recent years, triggered by U.S. Rep. Luke Messer (R., Ind.) proposing adding pieces of art as an extension to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), a 1970 law in place to make it more difficult for mobsters and terrorists to launder money. At the time Messer proposed the addendum to the BSA, many argued that regulations already existed that made it difficult for fraudulent activity to take place. They further argued that art collections and museums having to fill out extra paperwork to track each sale and purchase would be financially crippling, much in the way that the regulations in Mexico damaged the art trade in that country.

At a Fashion Institute of Technology symposium in 2018, former Department of Homeland Security Special Agent James McAndrew argued, “There has not been an art dealer or collector convicted for laundering money through art.”

But, McAndrew’s quote does not prove that the practice isn’t happening so much as there aren’t many being arrested, charged, and convicted of money laundering art crimes. Many others disagree with McAndrew’s assertion, and there seems to be plenty of evidence contrary to his claim.

“The art market is an ideal playing ground for money laundering,” Thomas Christ, a board member of the Basel Institute on Governance, a Swiss nonprofit that has studied the issue, said to the New York Times in 2017. “We have to ask for clear transparency, where you got the money from, and where it is going.”