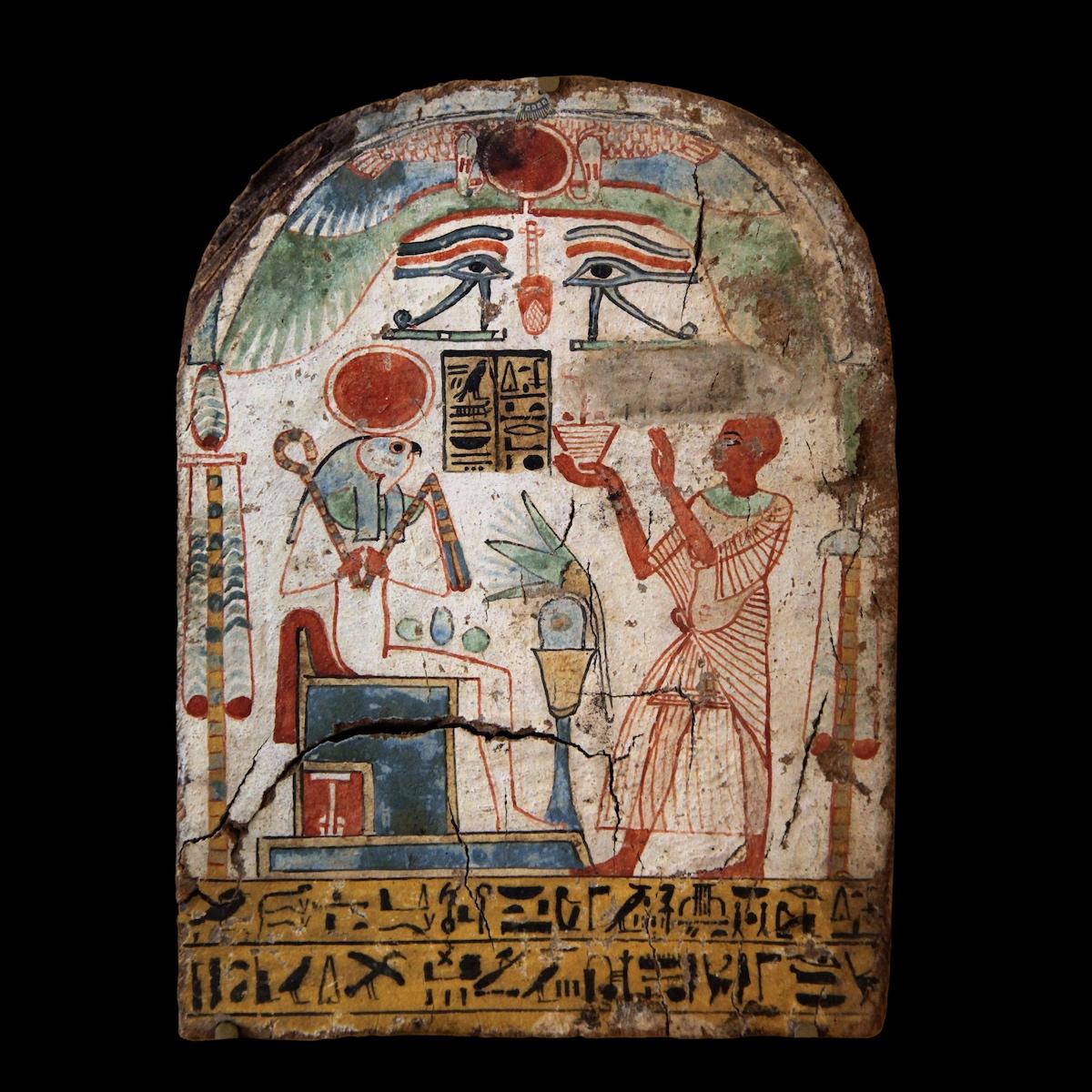

The faravahar derives from the image of the winged sun disk which permeates much Egyptian art; the motif (visible in the image of the Ra-Horakhty stela) originates from Ancient Egypt’s local pantheon (specifically the gods Horus, Set, and Osiris), and denoted the Pharaoh’s authority. The symbol evolved through Sumerian and Babylonian culture before the Assyrians repurposed it into a depiction of the god Ashur. This divine connotation likely translated into the Ahura Mazda after the fall of the Assyrian empire (between 1500 and 1000 BCE) and the culture’s diversification into the Alans, Bactrians, Parthians, and Persians. Around this time, the prophet Zarathustra (or Zoroaster in Greek) rewrote Early Iranian polytheistic religion into Zoroastrianism, which in turn became the principal religion of the Achaemenid (550 to 330 BCE), Parthian (247 to 224 CE), and Sasanian (224 to 651 CE) empires. Just as Egypt and ancient Middle Eastern civilizations birthed Zoroastrianism, so was the winged sun disk subsumed by the faravahar.

Rama, Stele of Ra-Horakhty

A visual history of Zoroastrianism—allegedly humanity’s oldest monotheistic religion—materializes only to the most determined eyes. Buried under millennia of crucifixes, stars of David, and crescent moons, symbols of this four-thousand-year-old faith have been overshadowed and repurposed as cultural and political motifs; yet like its worshippers, Zoroastrian art has not vanished, but rather learned silently to adapt and influence.

The most salient symbol of Zoroastrianism is the faravahar, which illustrates the faith’s dualistic structure. Likely representative of the Ahura Mazda, the omnipotent Lord of Wisdom, the faravahar’s human male visage mirrors and relates to his human followers. His horizontal wings contain three sets of feathers, encapsulating the Zoroastrian motto, “humata, hukhta, hvrashta,” or “good thoughts, good words, good deeds,” while the lower tail feathers connote the inverse. The two coils underneath the human form correspond to Sepanta Minu and Ankareh Minu, or negativity and positivity, with the Ahura Mazda facing goodness. The ring he clutches in his right hand represents determination toward righteousness, and the ring of the covenant. Yet while the icon of the Ahura Mazda encompasses Zoroastrianism’s cosmology, the faravahar’s origins perpetuate an older cultural motif.

Gold plaque from the Oxus treasure, 5th to 4th Century

The Darius Seal, 6th to 5th Century CE

As the religion drew from its placement near the Sistan basin, it also loaned its aesthetic to Judaism and incipient Christianity and Islam, adding new generational obstacles to identifying its art history. The British Museum carries a gold votive plaque in its Oxus Treasure trove, featuring a male figure clad in the typical, heavily embroidered fashion of Medes, carrying a barsom in his right hand. This barsom, or bundle of wooden sticks, served ancient Zoroastrian rituals and identifies the man as most likely a Zoroastrian priest, whose duty was to stoke and tend to the Eternal Flame in Zoroastrian Fire Temples.

Such clues and recurrences have become an essential part of Zoroastrian investigation; The Darius Seal displays its king at hunt, torso turned defiantly toward his viewer, as Darius repeatedly shoots a muscular lion, while his horses trample another. His clearly carved dentate diadem identifies the emperor, while a centered Ahura Mazda shines above, blessing the king’s conquest and dominating the scene. Yet the cylinder remains a debatable Zoroastrian object. While Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid empire and predecessor of Darius I, was a staunch Zoroastrian, Darius’ faith is uncertain. Only his religious tolerance is established, potentially turning the cylinder into an ode to religious unity, instead of a celebration of Zoroastrianism.

Napishtim, Faravahar, Persepolis

The religion still dictates free worship, and staunchly opposes proselytization; after the Muslim Conquest of Persia in the 7th century CE, a small number of Zoroastrians fled to western India. Known as Parsis, or Parsees (derived from Pars or Persia), the Indian monarch demanded the refugees never marry or proselytize his subjects, and so the Parsi and Zoroastrian population has dwindled to approximately 130,000 worldwide. British colonialism offered the opportunity for Zoroastrians to become an economically powerful minority—and indeed, in the twenty-first century, a Parsi hand helps drive nearly every major industry in the world, ranging from tea production to steel manufacturing. Yet the culture remains modestly invisible.

This perhaps is why the recognition of Zoroastrian art and cultural forcefulness is becoming increasingly pressing. The Parsi honor system dictates an impending self-immolation, but it does not insist upon self-erasure—Zoroastrian imagery remains eternally, if invisibly, inextricable from our most celebrated histories. Deriving from one of the most powerful empires in history, today Zoroastrian art celebrates a quietly puissant community, and translates into consistent contemporary reminders for “good thoughts, good words, good deeds.”