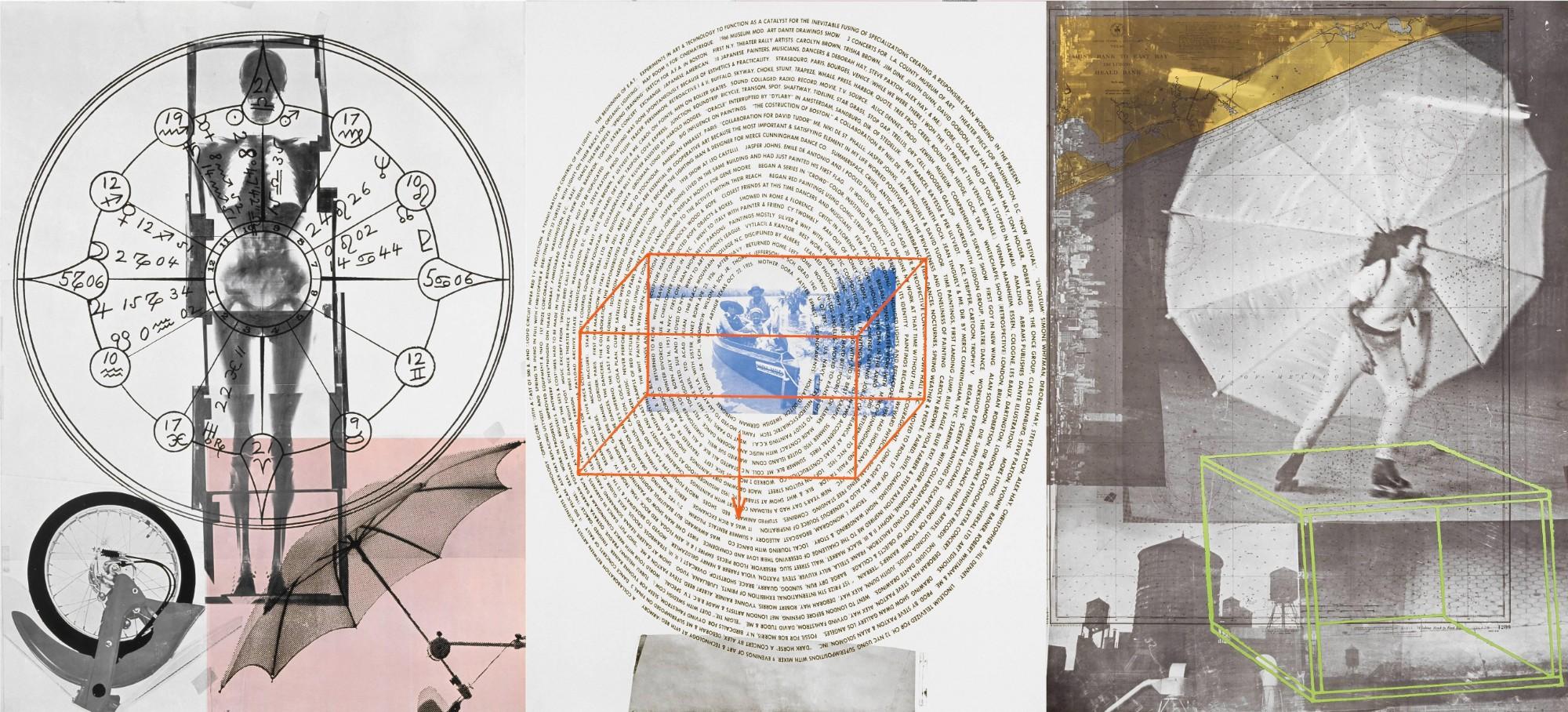

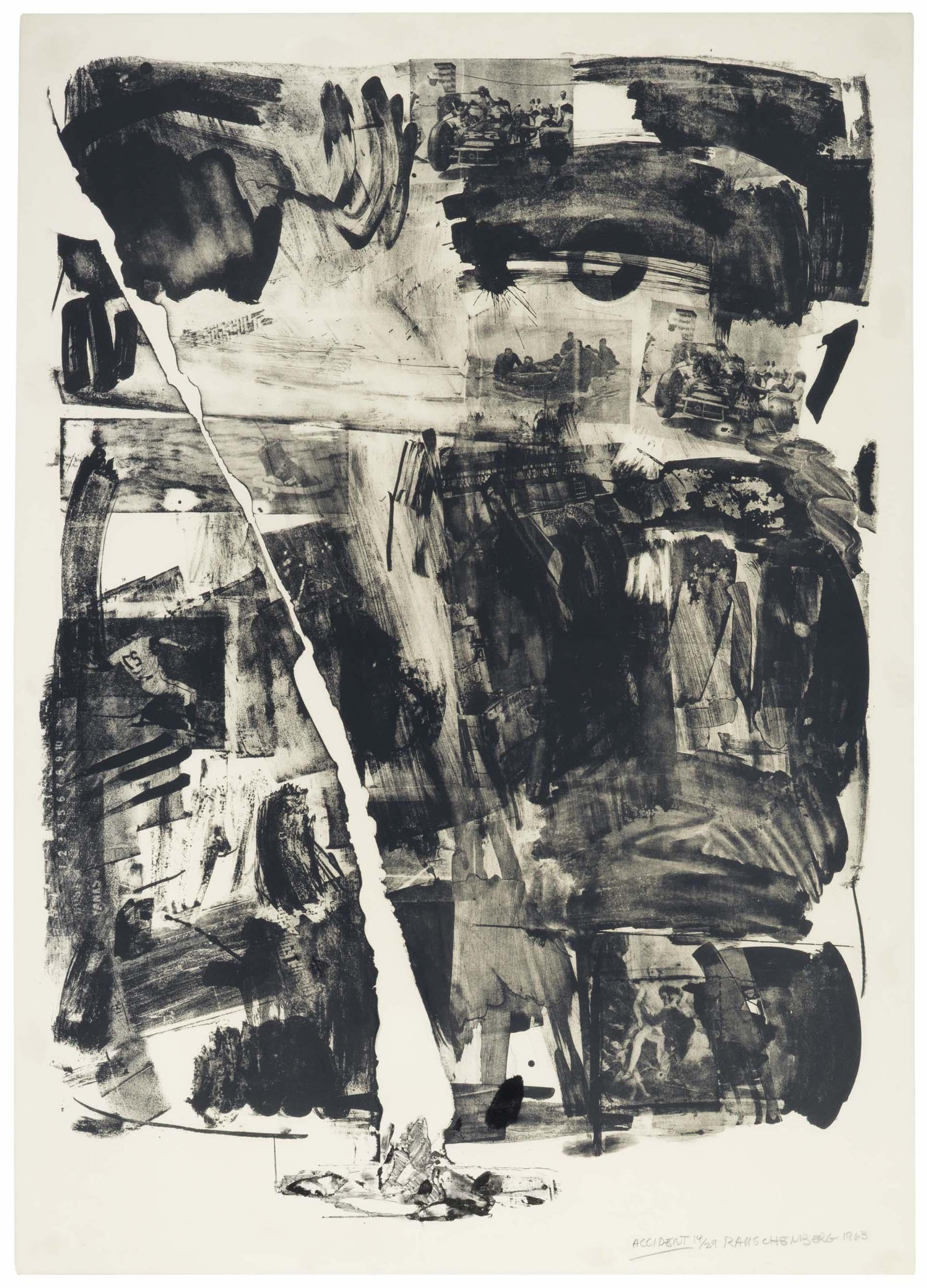

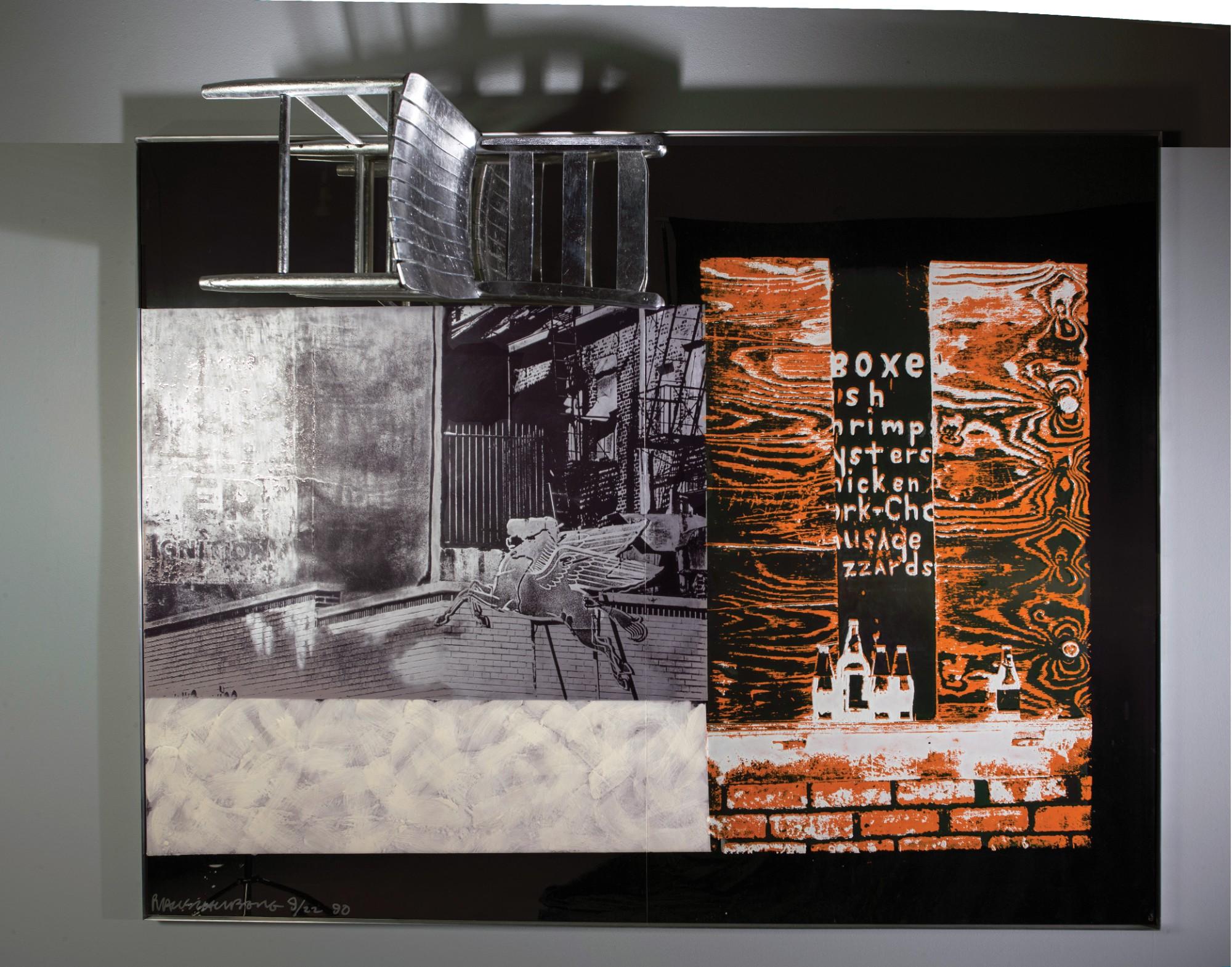

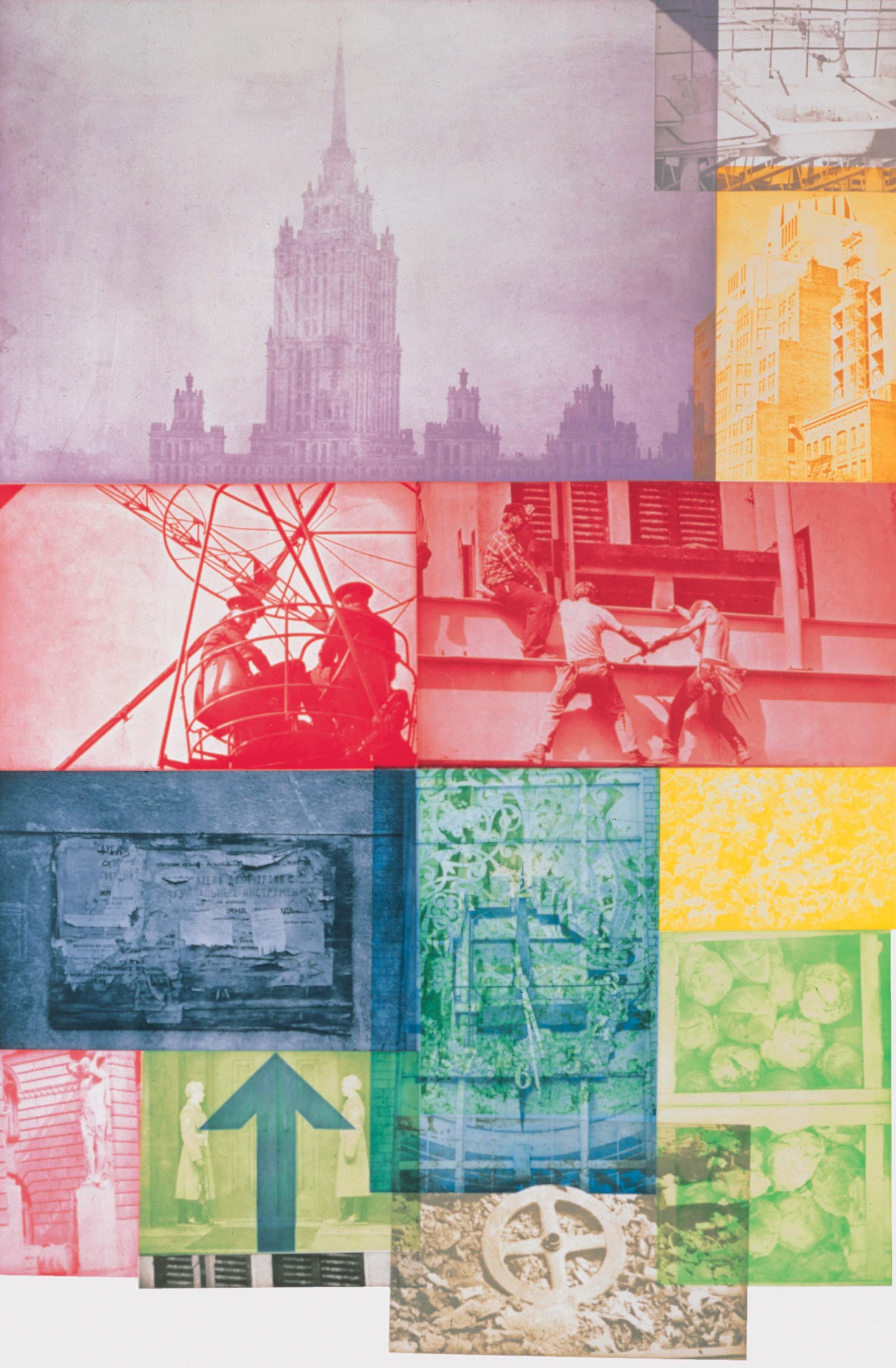

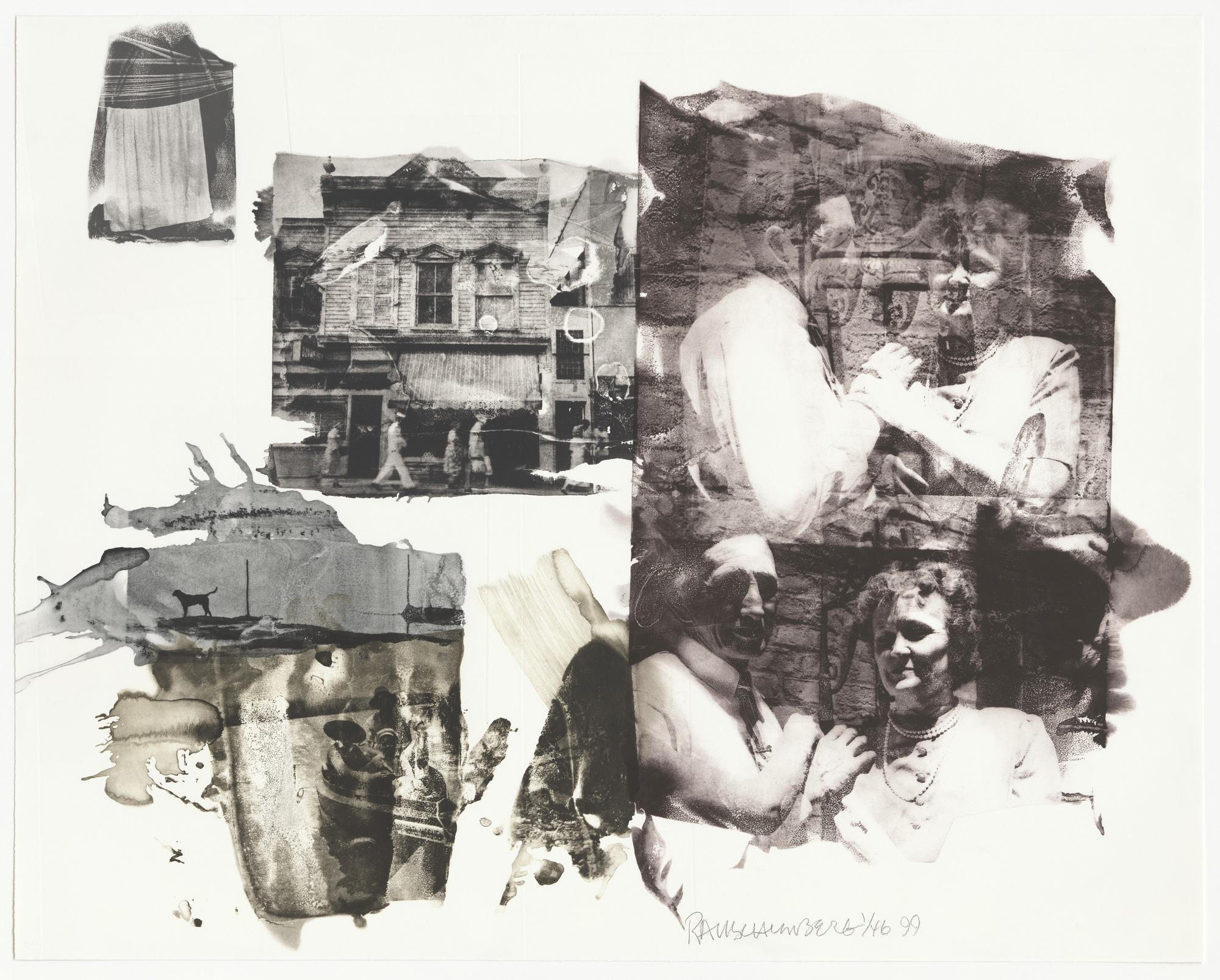

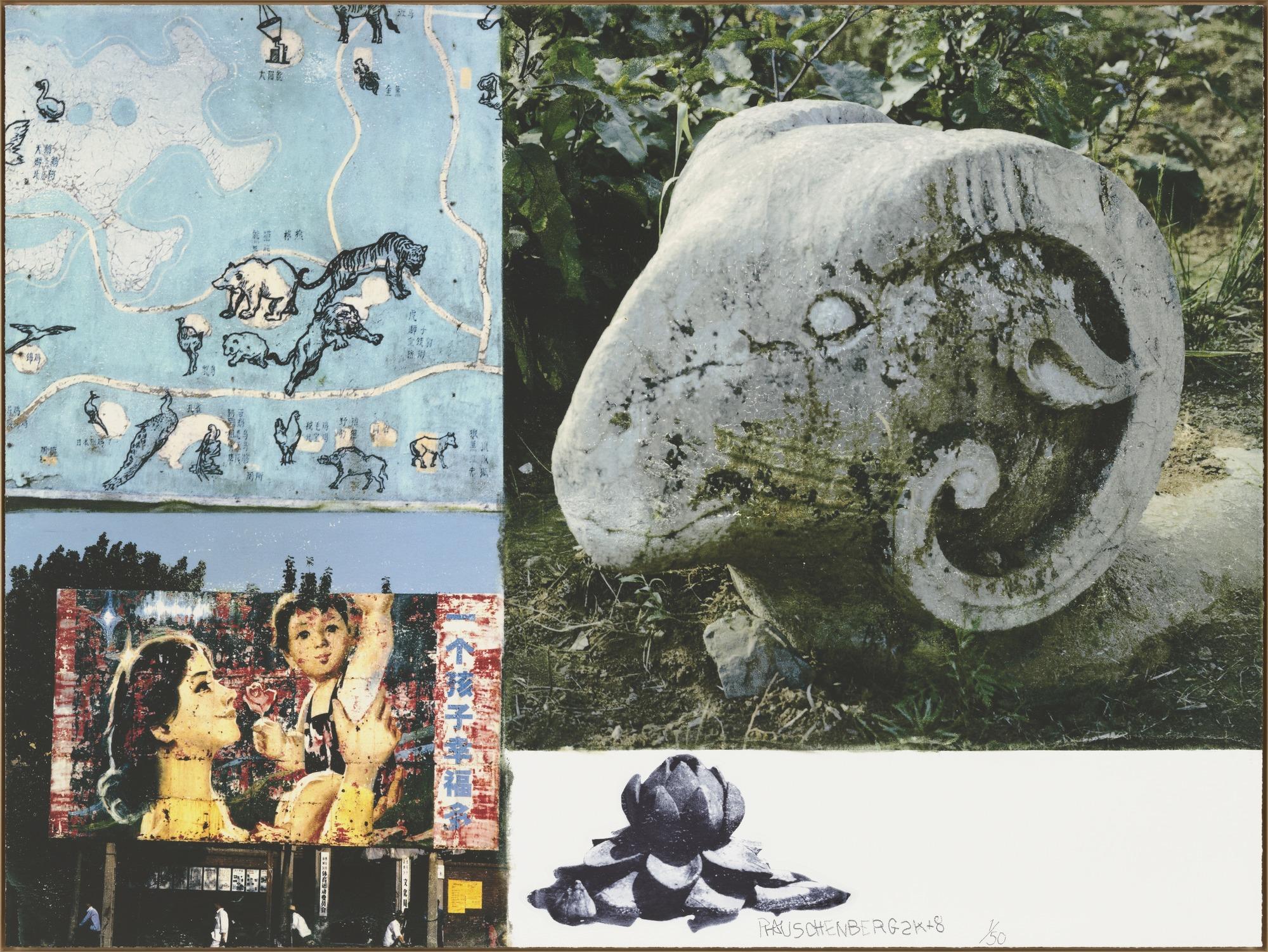

Madden—a retired developer, longtime art collector and early proponent of public art—met Rauschenberg and purchased several of his works. Madden donated his extensive collection now known as The Madden Collection at the University of Denver. Several of Madden’s Rauschenbergs are on loan for the MOA exhibition that spans 1962 to 2008.

In 2017, MOA exhibited Unerased Journeys: A Survey of Works by Darryl Pottorf. Pottorf, a Rauschenberg protégé and companion for 38 years, sat for an interview prior to the exhibition and recalled the life and death of one of the 20th century’s greatest American artists.

“We talked nonstop,” Pottorf said of Rauschenberg. “We had dinner together every night. Our brains crossed. We were traveling a lot, talking on jets, in hotels, experiencing all these things together. We went to the White House six times. We had a lot of the same nature. Our personality traits were alike. We liked anything new: new food, new experiences.”