Mix’s text, which resulted from studio visits with Noguchi and was likely written on spec for a design magazine, was never published, either. But it led to the Noguchi Museum’s ongoing exhibition that explores the artist’s frustrated quest to design the perfect ashtray. (The museum is currently closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but much of the exhibition can be viewed online.) Senior curator Dakin Hart had seen the magazine layouts several years ago, but only with recent efforts to organize and digitize the institution's archives did a fuller story begin to come together. The exhibition includes letters that capture Noguchi’s enthusiasm towards his project, patents with drawings (that the artist prepared but never submitted), and ashtrays that the museum 3D printed based on Noguchi’s sketches.

Isamu Noguchi, Ashtray Prototypes, c. 1944. Plaster.

Like many of his time, Isamu Noguchi was a smoker. The Japanese American artist saw the prosaic act, from the lighting to snubbing out of a cigarette, as a pleasurable social ritual, not unlike the refined rites of a traditional tea ceremony. It should not be so unexpected, then, that a man who spent his career envisioning sculptures as an intentional part of everyday environments attempted to design a new kind of ashtray. Noguchi envisioned his receptacle as not only attractive but also having unparalleled efficiency. It also had to be perfect, and he toiled over multiple prototypes that exemplified his diversified thinking and particular design sensibilities.

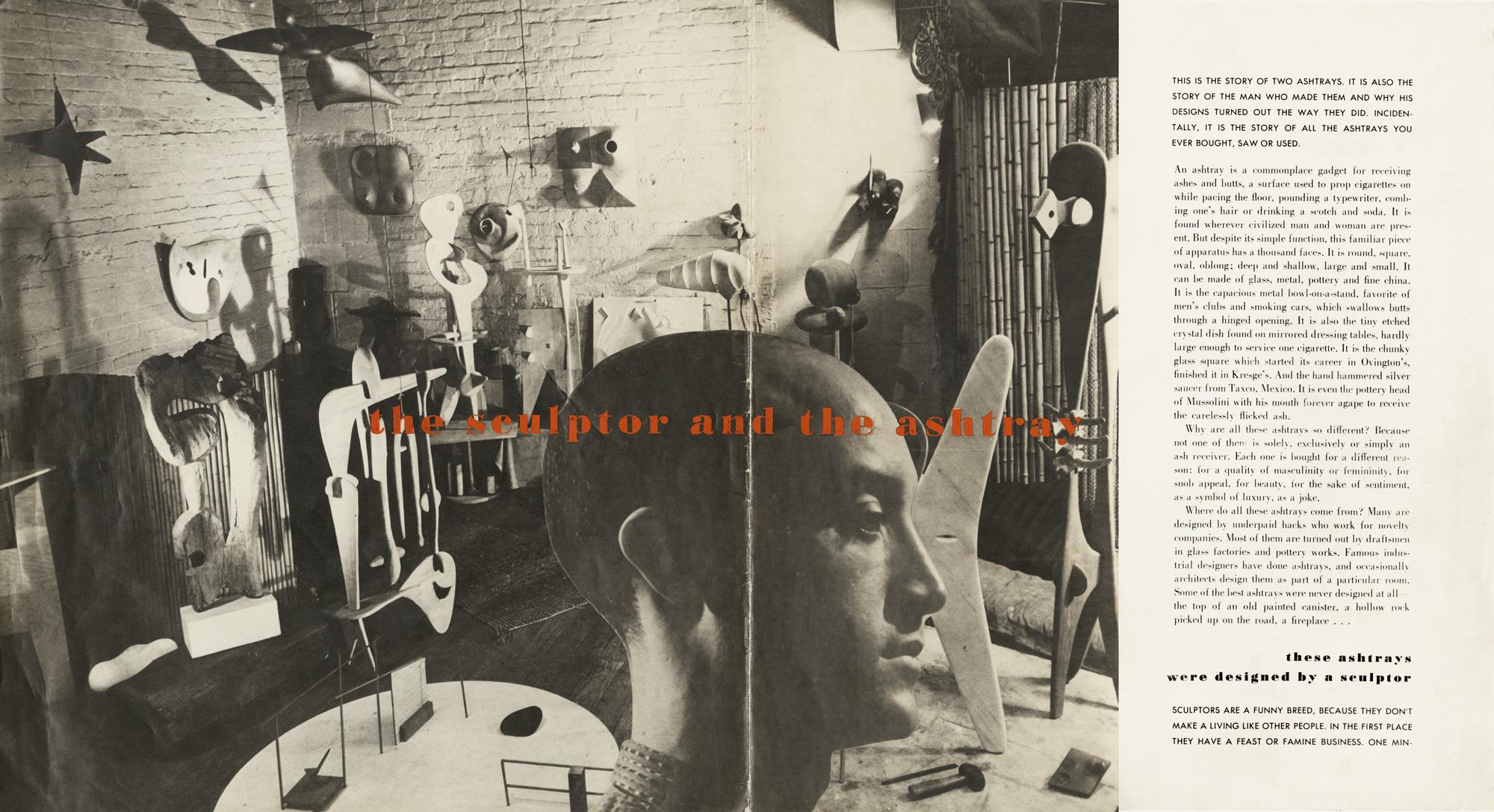

“Even to this small and relatively unimportant object, Noguchi gave the terrific imprint of his whole personality,” the architectural writer Mary Mix wrote in 1944, the year Noguchi began developing his ashtray ideas. Although he came up with two concepts—one biomorphic bowl and one industrial design featuring bullet-shaped projections—neither went into production.

Spread from unpublished magazine article by Mary Mix, “The Sculptor and the Ashtray,” c. 1944. Printed proof with hand coloring.

In 1944, Noguchi was a struggling artist, with no regular income or business prospects. The ashtray—humble, ubiquitous, and, in his eyes, flawed—proposed an interior design challenge that carried the potential of wealth. Photographs suggest that he himself favored a simple clamshell and a cubed-shaped ashtray by the Italian designer Bruno Munari. “Noguchi turning his attention to the ashtray, which he actually calls this ‘silly little trinket’ at one point—he had hopes that it would make him rich in a way that was easy,” Hart said. “At that time everybody smoked and most people had multiple ashtrays, so it was a chance to have a substantial impact on daily life.”

Ashtray design by Isamu Noguchi, pictured in unpublished magazine article by Mary Mix, “The Sculptor and the Ashtray,” c. 1944.

Noguchi’s first designs were asymmetrical bowls with organic contours and various indentations for resting multiple cigarettes at once. They recall landscape features in miniature, from waves to caldera, carrying his embrace of natural elements that permeate through his work, from his stone sculptures to his cohesive playground environments. Noguchi modeled nine iterations in plaster, with the final one featuring a large broad rim for leaning cigarettes against from any angle. Initially, he believed he'd achieved his goal. ”Then virtually the next day, he says it’s garbage because it’s just like any other ashtray,” Hart said.

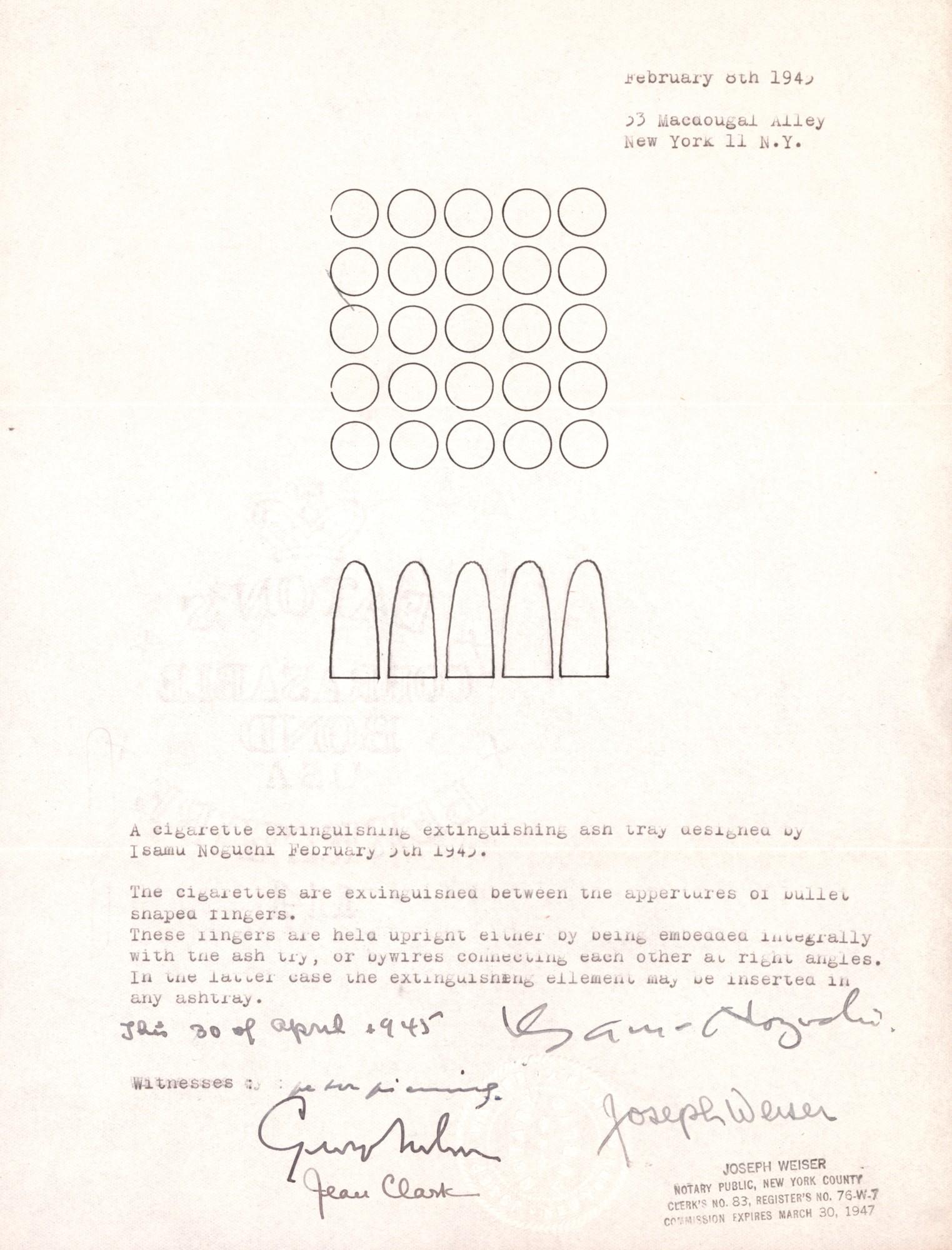

Noguchi’s second concept was more high-functioning. Its core unit consists of a grid of upright “bullet-shaped fingers,” as Noguchi described them in a patent document, upon which users could rest cigarettes before snubbing them out by jabbing them in between these short projections. The simplest version, likely meant to be made of metal, could be placed atop any other ashtray; another featured its own holder that the bullet unit would fit into, making it easy to clean. A third iteration, possibly meant to be glass blown, was the most complex, with individual bullets that consumers could buy in different colors to customize their own modular ashtray.

Notarized design drawing dated February 8, 1945, for a patent application for an ashtray design by Isamu Noguchi.

But while these were designed deliberately for mass manufacturing, Noguchi’s ashtrays proved too complicated for mass manufacture. “He wasn’t willing to take it far enough to make it possible to mass-produce—he got caught up in his own design and wasn't willing to simplify it,” Kate Wiener, the museum’s assistant curator, said. “But he really believed in what he made. He thought it was this true innovation.”

Prototype of a two-part ashtray created from original schematic drawings by Isamu Noguchi, 1944–45. 3D print, produced 2020.

Noguchi eventually shifted his full attention to other household objects, most notably his now-famous coffee table and his popular Akari paper lamps. (He also gave up smoking later in life.) But his ashtray ideas, although largely forgotten, are valuable portals into his mind. They speak to the artist’s restless spirit of inquiry, sensitivity to materials, and belief in the power of objects—no matter how small—to shape and change their surroundings.

“The exhibition is meant to unpeel the Noguchi onion,” Hart said. “It looks at the fact that with Noguchi, everything is bifurcated and always hybrid.”