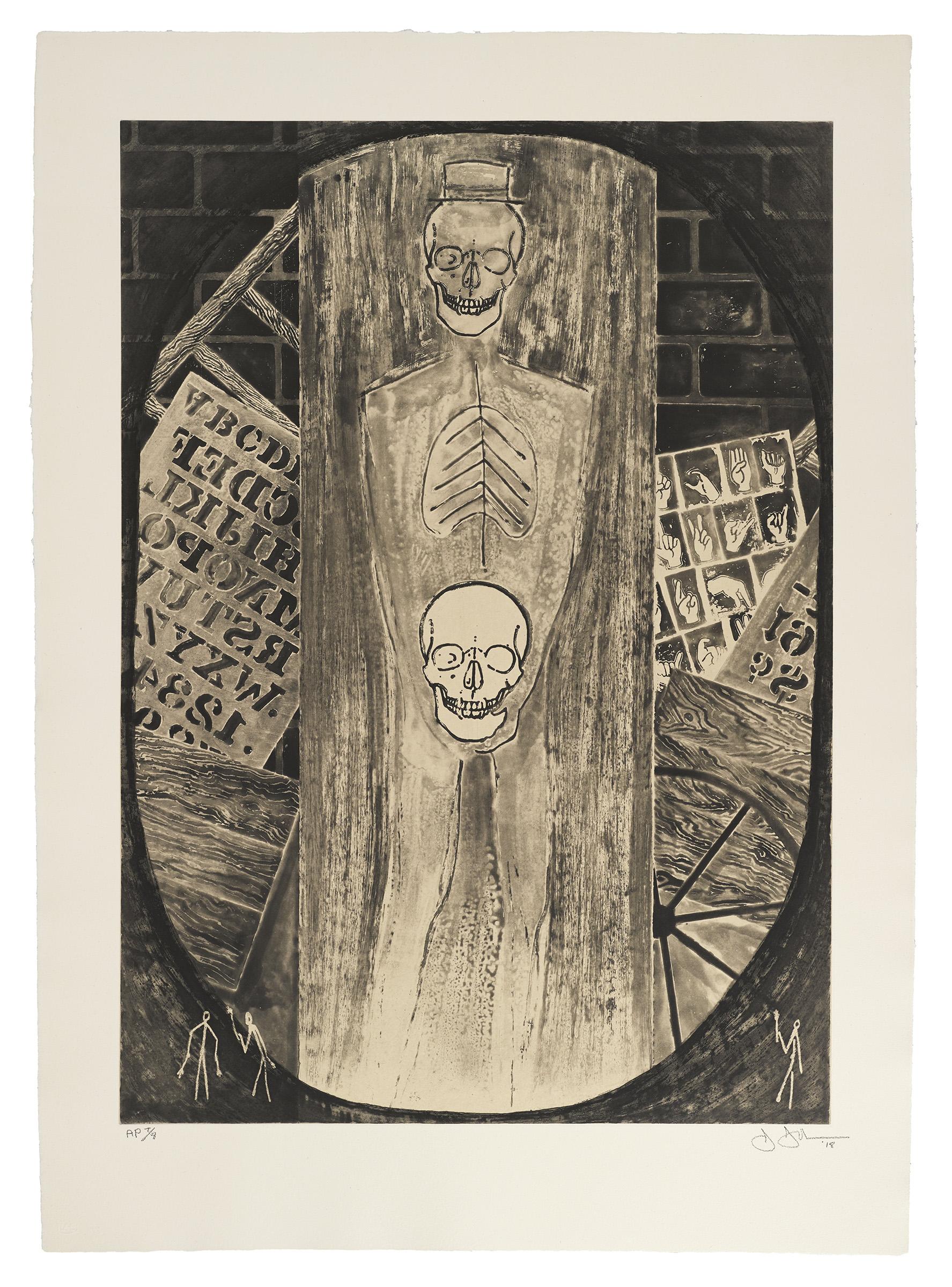

Jasper Johns defied most categories of contemporary art. “People tried at the time to slot him and [Robert] Rauschenberg into something they called Neo-Dada— they figured this was anti-art,” Rothfuss says. "But that really wasn't what he was doing either.”

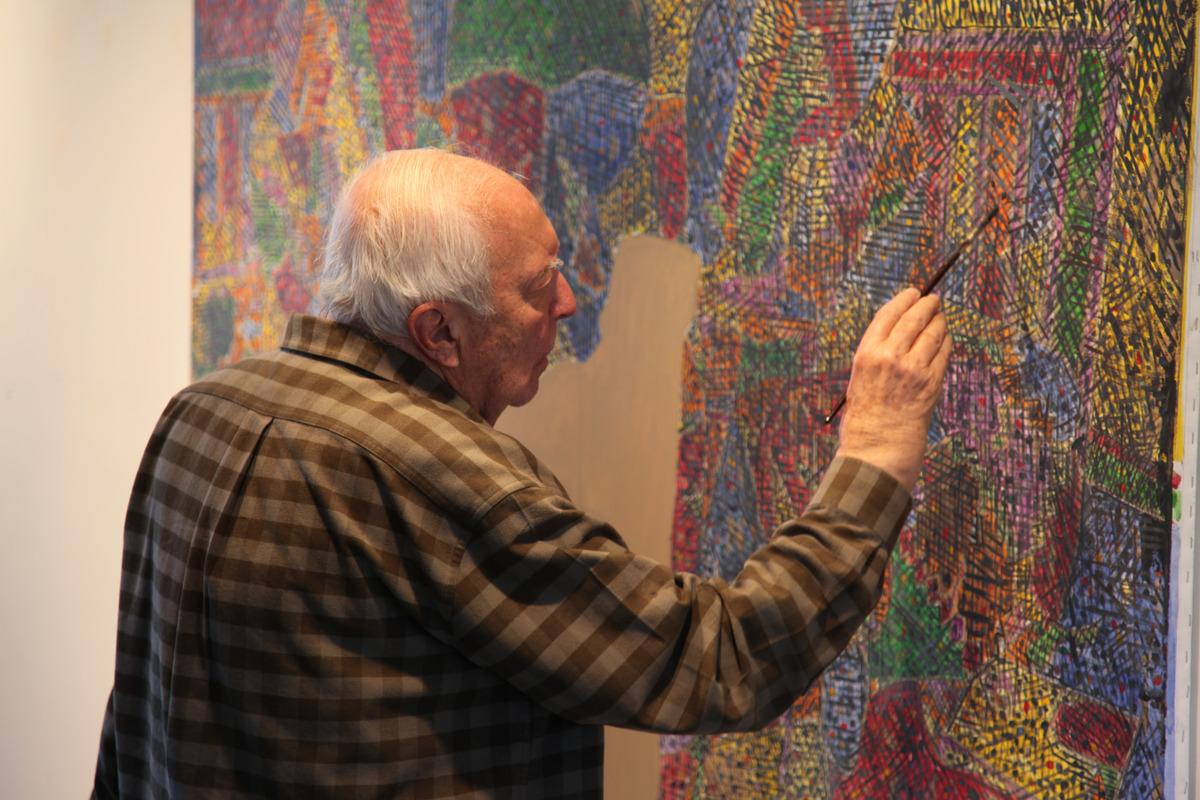

Instead, Johns forged his own journey as he investigated pictorial structures and images. “Once he gained his renown, people were just interested in what is he going to do next,” Rothfuss says. “He's got a career path that doesn't fit into anything.”