The gift includes approximately 375 works by more than 125 artists, with 288 works by artists other than Waters. In addition to Twombly, Sherman, and Warhol, the collection contains works by Diane Arbus, Roy Lichtenstein, Thomas Demand, Nan Goldin, Catherine Opie, Richard Prince, and Christopher Wool, among others.

Waters also donated 87 prints, sculptures, mixed-media, and video pieces he created. That will make the BMA the greatest single repository of his work and will enable it to provide, in perpetuity, a comprehensive view of Waters’ vision and approach.

In return, the museum board said it would name two restrooms and a rotunda in the European art galleries after him. That is not a putdown. Known for his raunchy humor and offbeat way of thinking, Waters said he asked to have his name on the walls of the men’s and women’s bathrooms, which will become gender-neutral and will be known as The John Waters Restrooms.

“I fought for that,” he said. “People thought I was kidding.”

Waters expressed hope that the restrooms might become a new tourist destination for Baltimore, joining Edgar Allan Poe’s grave and the USS Constellation: “Maybe people will come from all over the world to eliminate there.”

John’s John. The Waters Closet. The jokes are writing themselves. But “going to the bathroom can be art, too,” he told a local TV station.

As the owner of contemporary art by luminaries such as Cy Twombly, Cindy Sherman, and Andy Warhol, Baltimore-based writer and filmmaker John Waters might have considered offering his collection to a large national museum because of its prestige, reputation, and attendance.

But Waters decided to give his collection to a hometown institution, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), when he passes away. This week, he spoke to Art & Object about this decision and what it means to him.

Besides being grateful to the Baltimore museum that sparked his love of art and supported his work over the years, Waters said, he hopes to encourage other collectors to think about giving their best pieces to their hometown museums, the places that potentially stand to benefit the most from their foresight and generosity.

“It means more if you leave it to the Baltimore Museum of Art than it might if you left it to the obvious bigger ones,” he said. “A lot of people leave them stuff.”

Known for being fiercely loyal to his hometown of Baltimore (he has filmed seventeen movies there), Waters announced his decision this month. It is no small gift.

Though he’s perhaps best known for films such as Hairspray and Pink Flamingos, bestsellers such as Role Models and Carsick, and nicknames such as “The Pope of Trash” and “The Prince of Puke,” Waters, 74, has been collecting fine art for more than five decades. He’s also a visual artist, the subject of a recent retrospective entitled John Waters: Indecent Exposure at the BMA and the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio.

Tadashi Kawamata, Destruction no. 8, 2016. From the collection of John Waters.

Gregory Green, Work Space #7, 1998.

Neither the museum nor the donor have disclosed what Waters’ collection might be worth. But according to director Christopher Bedford, it is “one of the most significant collection gifts in our history.” He said it reflects “an acute personal sensibility” that “harnesses the power of art to elicit humor, provoke questions, and challenge long-held traditions“ and “melds seamlessly with the BMA’s own mission to upend the standard narrations of art history.”

The works are currently spread over several residences Waters has, in Baltimore, New York City, and San Francisco, as well as his studio and office. Waters said the art he’s giving to the museum represents the majority of what he owns, although he’s saving some pieces to leave to friends. As part of the gift, Waters will lend his collection for an “inaugural” exhibit sometime in the next five years. The museum has also agreed to prominently display five works from the collection, including one by Waters, at all times.

The gift came at a moment when the museum could benefit from some upbeat news.

For much of the fall, the museum has been caught up in a controversy over a plan to sell three major works to raise at least $65 million to support initiatives intended to promote diversity within the institution, in hiring, programming, and acquisitions. The works were: 3 (1987-1988) by Brice Marden; 1957-G (1957) by Clyfford Still, and The Last Supper (1986) by Andy Warhol.

The plan came about in response to the Association of Art Museum Directors’ temporary relaxation of rules on deaccessioning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. But at least two prospective donors, both former BMA board chairs, said they were canceling gifts reportedly worth millions because they objected to the sale, and it has been “paused” for now.

Waters said the timing of the announcement about his donation turned out to be “weird” because of the controversy. He said his donation had quietly been in the works for more than a year, long before the deaccessioning plan was proposed, and it was always supposed to be announced this fall. He said his gift is restricted, meaning the museum can’t sell what he donates.

To complicate matters, Waters said, while he supports the museum’s goal of promoting diversity, he didn’t support the sale of the three paintings. At the same time, he said, he’s a Baltimore booster and had decided long ago that he wanted to give his collection to his hometown museum. “I wasn’t going to turn against the museum and take my gift away because of one thing,” he said. “I wanted it to go here.”

Waters stressed that he fully supports Bedford’s efforts to promote diversity and social equity. “No curator could ever come to Baltimore and start a job in a city that is 70 percent African-American without completely having that vision ahead of them.”

Part of the reason he was so set on giving his collection to the BMA, Waters said, is that it’s where he first learned about the power of art. He said his parents took him there when he was a boy in the 1950s, and the first work of art he ever bought was a $2 Joan Miró poster from its gift shop.

“After taking it home and hanging it on my bedroom wall at my parents’ house, I realized from the hostile reaction of my neighborhood playmates that art could provoke, shock, and cause trouble,” he said. “I became a collector for life.”

Later, when he began making films, the museum was the first institution to give him a retrospective, and it has showcased his work as a visual artist. So for him, the donation is a way to give back to the museum for all it has given him.

“I’m really thrilled that my home town is getting all the work that I’ve spent my whole life collecting,” he said. “It should end up here, where I first was challenged by contemporary art.”

The announcement of Waters’ gift has helped take attention away from the deaccessioning flap. Bedford and others say Waters’ collection will complement the museum’s holdings and fill gaps by adding works by artists who aren’t currently represented in the collection, such as Opie and Demand. The BMA is also getting some movie posters that Waters has collected as well as his collection of “fake food.”

One gap that Waters is helping fill is animal art, starting by donating a piece by Betsy the fingerpainting chimp from what is now the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore. In the 1950s, Betsy (1951–1960) was the first famous monkey painter, a smock-wearing trailblazer in a global assembly line of chimps and other primates who made art for fun and profit during what Waters has dubbed “The Golden Age of Monkey Art.”

Waters got his “monkey masterpiece” as a gift from the zoo when he turned seventy and wrote about Betsy in his latest book, Mr. Know-It-All. Curators say Betsy’s painting, whose title she kept to herself, will be the first work in the museum’s 95,000-object collection to be created by a non-human.

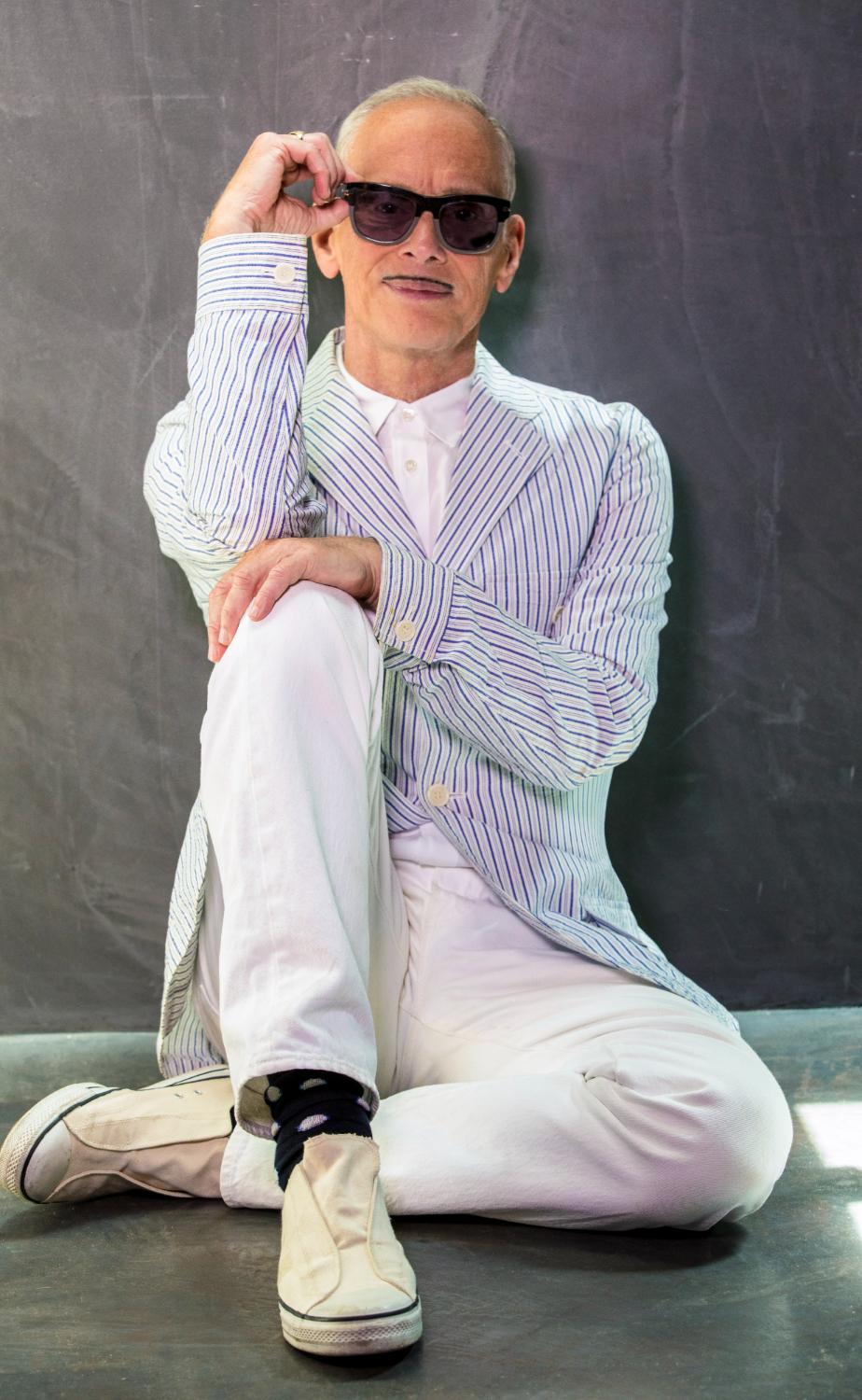

John Waters and his painting by Betsy the Chimp

Aside from the art he’s donating and the bathroom walls his name will be on, observers say, just the increased attention that comes from getting his imprimatur—the John Waters seal of approval—is likely to benefit the museum. In recent years Nike, Nordstrom, and Saint Laurent menswear have hired him to model for them—even flown him to France in a pandemic—not because he can throw a ball better than anyone else but because they want some of his edginess and elan to rub off on them and help them sell their products.

In the same way, the association with John Waters has the potential to help the BMA. Commenters on social media are already suggesting that his gift could do wonders for the museum’s reputation and “brand,” if only by making it seem less stuffy. Move over Met, quips writer and illustrator P.J. Parkwood: “This museum is now the Shrine to Camp!”

Waters’ donation is drawing praise from others in his hometown who know where his collection might have ended up and understand the statement he’s making by keeping it local.

“One of John’s greatest attributes is his unconditional loyalty to Baltimore,” said writer and collector Stephen Salny. “John is Baltimore. Baltimore is John. “

“Hats off to John Waters, who so thoughtfully matched his collection of contemporary works with the needs and mission of the BMA,” said Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, founder and director of the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore.

“He thought of a way to help that could really make a difference,” Hoffberger said. “What a perfect destination for his art collection and what a wonderful example to all of us, to think about where what we have can do the most good.”