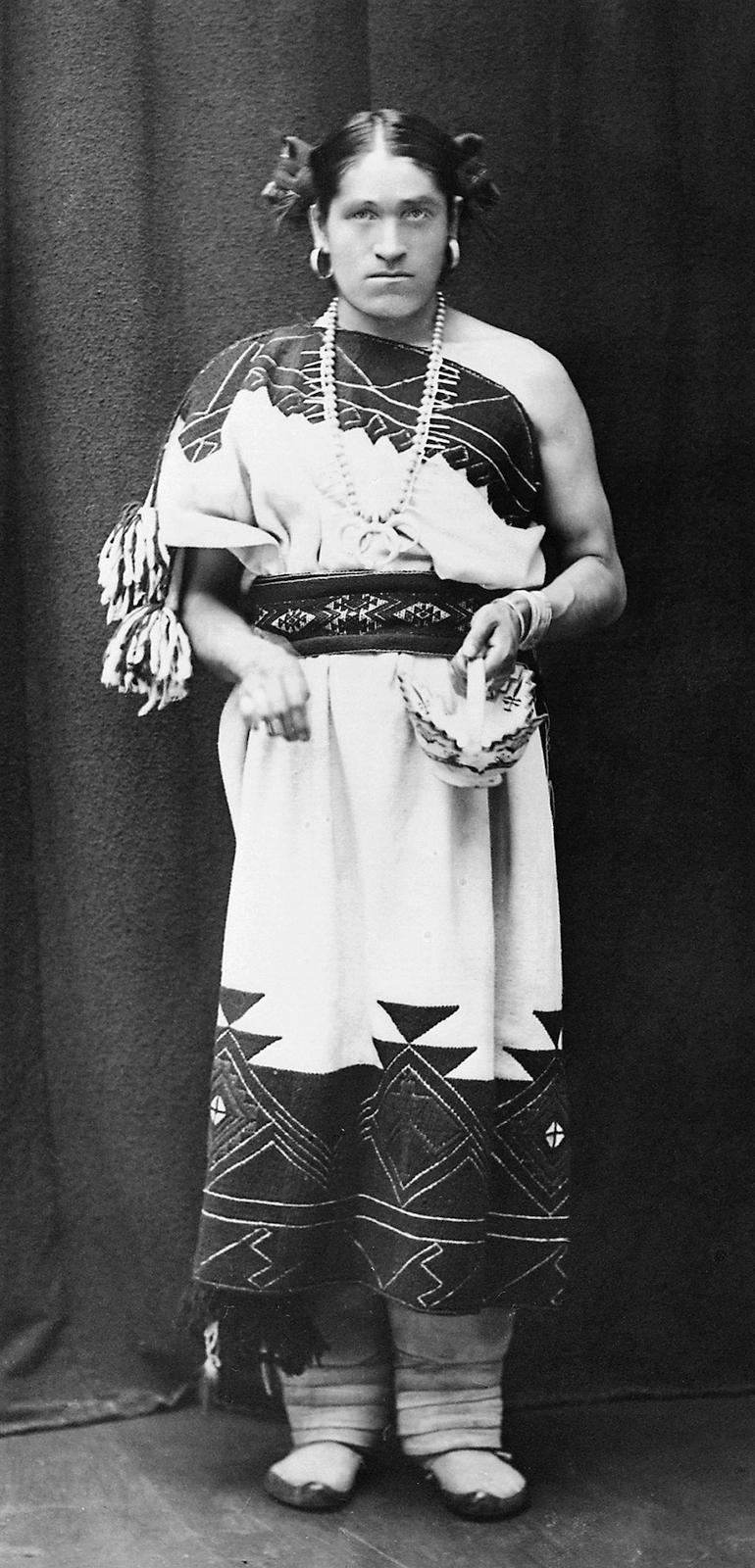

While Two-Spirit was popularized in the 1990s as a term to describe nonbinary individuals, the Zuni tribe has long-used Łamana to refer to a third gender. Revered as reflections of harmony and balance, Łamana are important spiritual leaders in Zuni culture.

According to historical documentation, the late We:wa used both male and female pronouns. However, following the guidance of Zuni advisors and the typical preferences of contemporary Indigenous Two-Spirit people, many publications opt to use “they/them” when referring to the late We:wa. This example will also be followed throughout this article.

Born in approximately 1849, in Zuni Pueblo (now known as New Mexico), the late We:wa began training at a young age in traditionally male and female tasks. Typically, Zuni men were warriors, weavers, hunters, farmers, priests, and political leaders while women ran the households, cooked, ground the cornmeal, and made ceremonial pottery.

Over the years, in addition to their performance of roles traditionally assigned to each gender, the late We:wa also led community mediation and became well-known as a revered community leader and an accomplished artist renowned for their skill with color and patterns.

As an adult, they learned English in order to facilitate communication with European colonists and to advocate for the protection of Zuni rights and culture. Their friendship with anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson was integral to the establishment of a cultural exchange that facilitated the late We:wa’s political activism and eventually led to the aforementioned recognition of Indigenous art as fine art. The late We:wa’s artwork played a key role in this process as they were one of the first Zuni artisans to sell their work to non-Indigenous buyers.