Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born on March 6, 1475 in the small Italian town of Caprese (now Caprese Michelangelo), where his father had taken a temporary government post following the failure of the family's banking business in Florence.

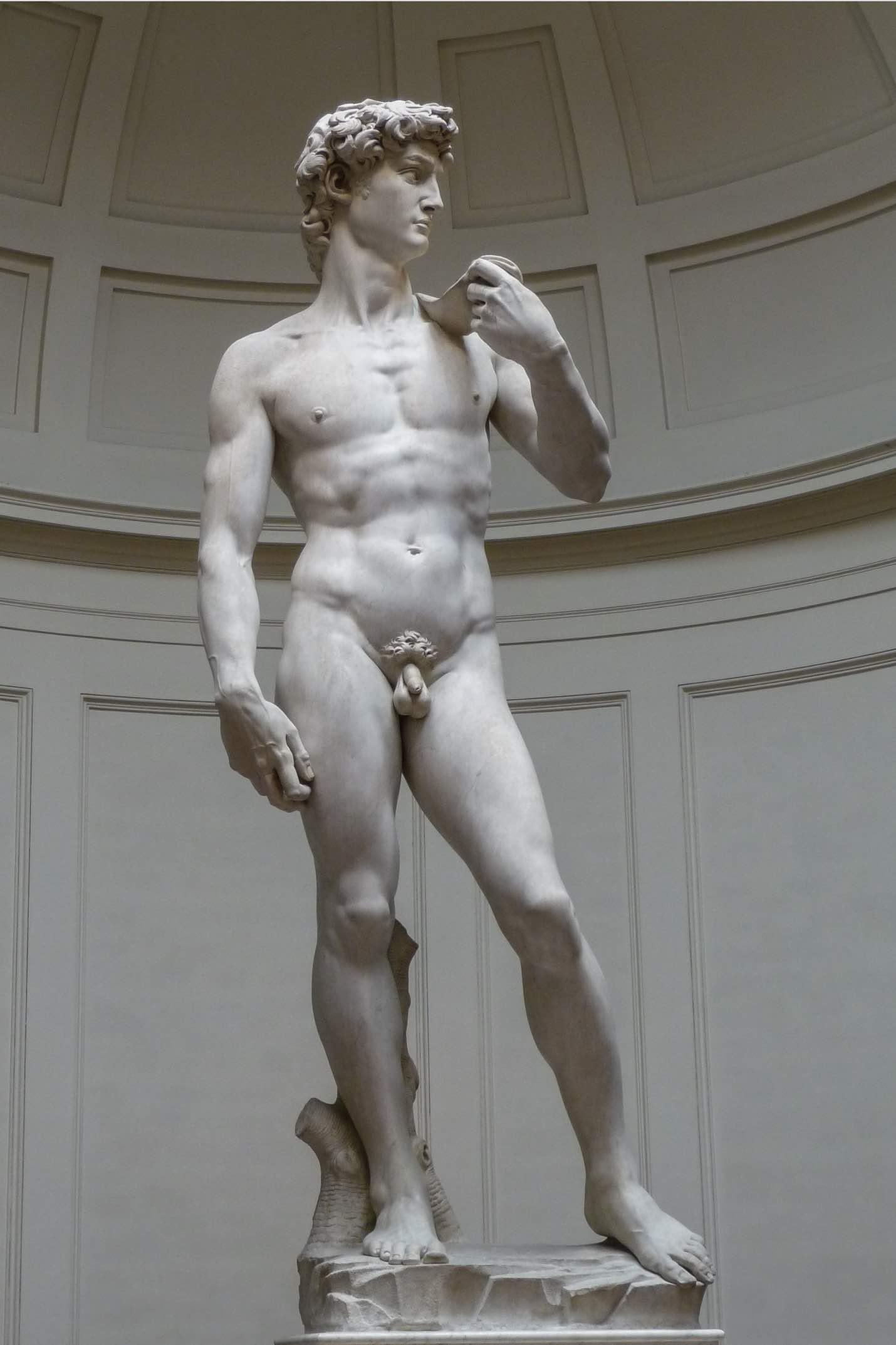

Several months after his birth, the artist's family returned to Florence, where the young Michelangelo was raised by a nanny and her husband, a stonecutter. During these years, the artist and his caretakers lived on his father’s small farm with a marble quarry. It is unsurprising that Michelangelo’s passion for working with marble was quickly cultivated.

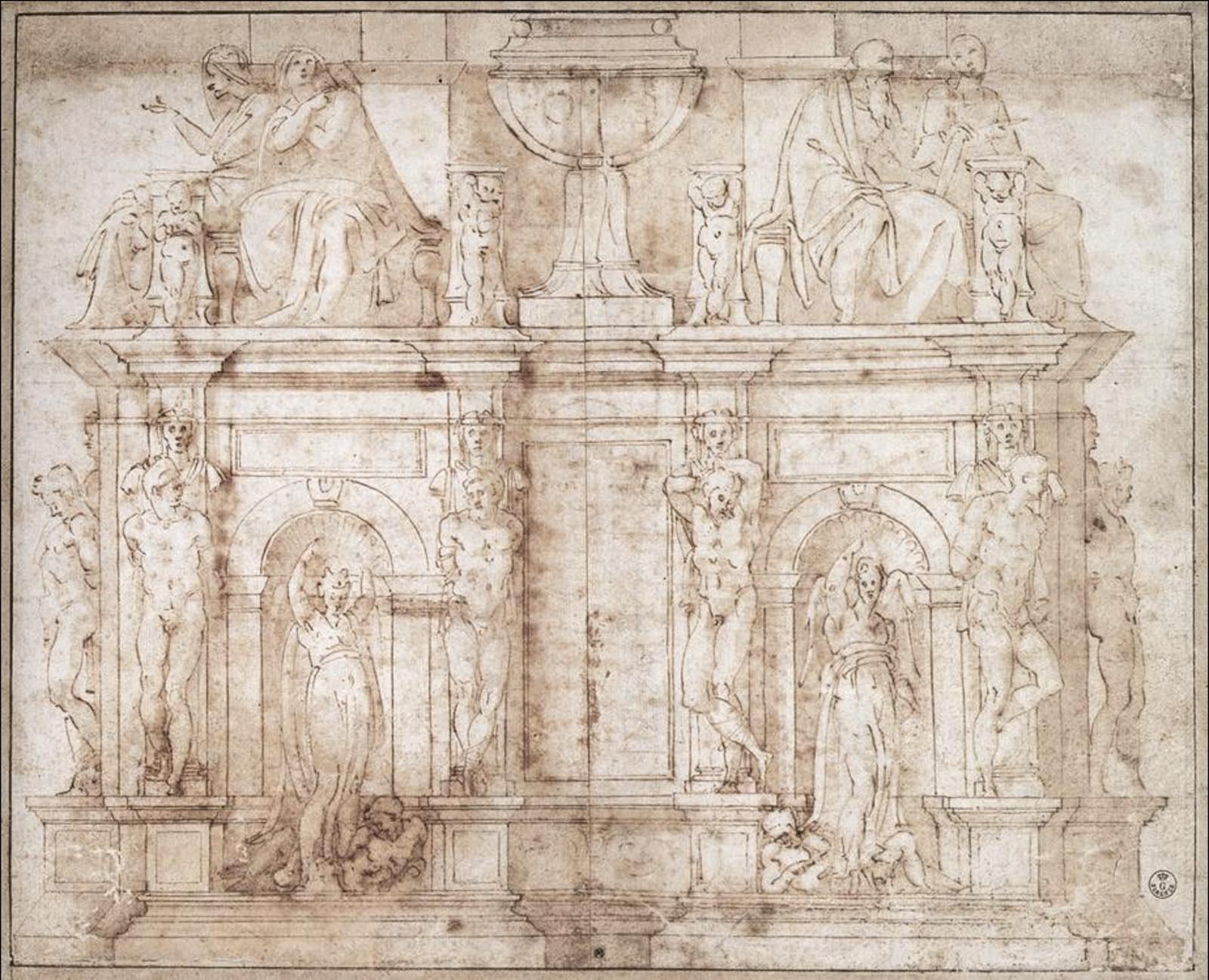

Michelangelo’s life and work was heavily influenced by contemporary developments in social and intellectual thought, particularly humanism. Florence in the late fifteenth century was the center of Italian art and learning.