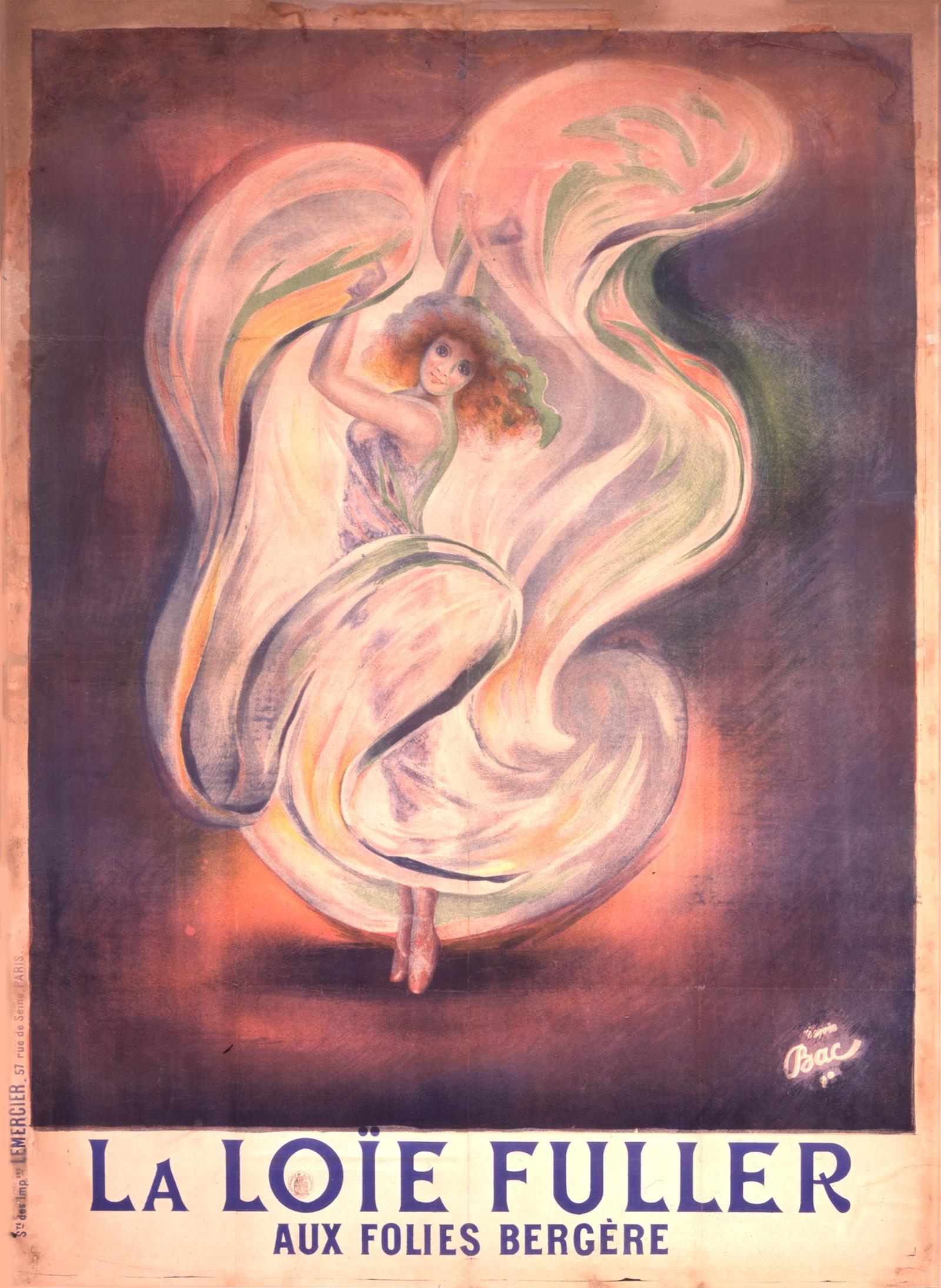

Fuller’s performances involved huge layers of swirling, colorful fabrics. She sewed rods into these costumes to help them pirouette over and around her body as she moved. The colored lights she projected onto her stages seemed to dye her fabrics and body, an effect that hand-colored film would later try to replicate. These live and documented performances became her signature act and enraptured audiences and other image-makers of the period. In still images, and even in films, it is still difficult to discern where the dancer’s body begins and where her elaborate, sculptural costuming ends.

Fuller toured extensively and her performances were unlike anything that Parisian and American audiences had seen before. She herself did not fit the mold of a typical showgirl: she was older than most when she became a celebrity, did not have any formal dance training, and was criticized for not being a naturally gifted, or graceful, dancer. But she was a master of illusion, costuming, and technology—all of which she harnessed into an unprecedented kind of visual feast that eclipsed her unglamorous offstage persona in favor of something utterly new. She became one of the most well-known figures in Belle Époque performance.