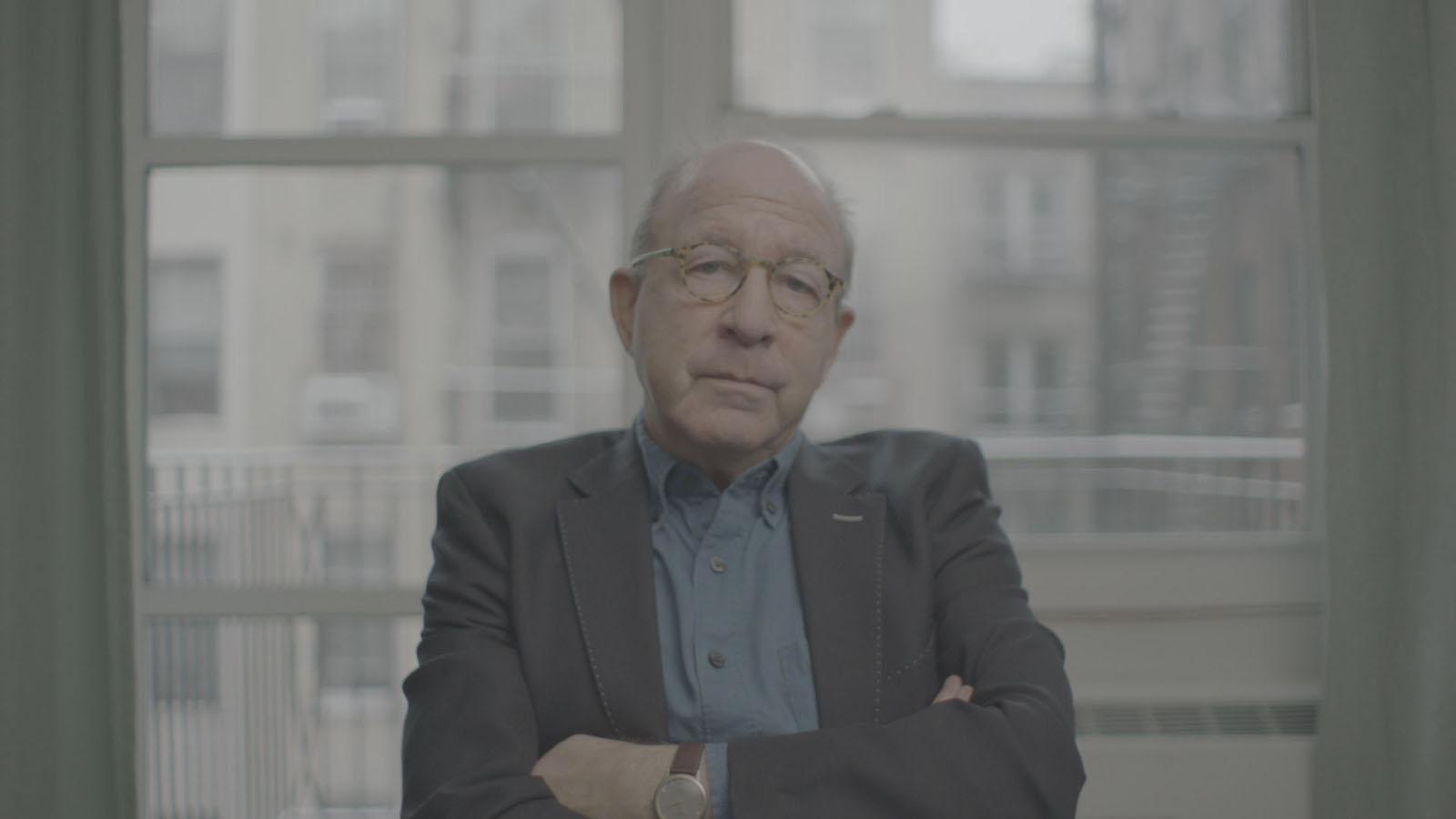

Modestini’s restoration seems to be what casts the greatest doubts in the minds of many, notably the movie’s resident curmudgeon, Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Magazine critic Jerry Saltz. Objecting to a Leonardo attribution mainly on the grounds that a Renaissance masterpiece isn’t likely to turn up in New Orleans of all places, he goes out of his way to trash Modestini’s restoration.

Doubts or not, a committee of five scholars gathered in 2008 at London’s National Gallery to determine once and for all the painting’s author. Most, confronted with a canvas that has been greatly restored, demur, though they tend to lean in the direction of a Leonardo attribution. The problem is no one actually says it.

“As Maria Teresa Fiorio says she was never asked directly and she didn't understand the concept of the session, that it was used in the way it was used. And when you ask the curator, Luke Syson, he was convinced it was a Da Vinci and they invited scholars who they thought would be positive. They didn't invite Frank Zöllner from Leipzig, who is considered one of the most important Leonardo scholars. He’s a bit pissed off he wasn't invited, but maybe there's a reason for that. Syson was convinced of the attribution himself so that he took the positiveness from the scholars as a confirmation. And he didn’t find it appropriate to ask the question directly, is it a Leonardo or is it not, he felt the atmosphere, everyone is positive, it’s a Da Vinci.”

What followed was the 2011 blockbuster show, Leonardo da Vinci: Painter of the Court of Milan, which billed Salvator Mundi as an authenticated work by the artist. In the minds of most, this silenced questions on the painting’s attribution. It also gave dealer Warren Adelson the juice he needed to sell the work for $200 million, which he nearly did to the Dallas Museum, though they could not manage the purchase in the end. Stuck with the most important painting of his lifetime and no one to sell it to, Adelson was visited by freeport mercenary Yves Bouvier who smelled blood and an opportunity.