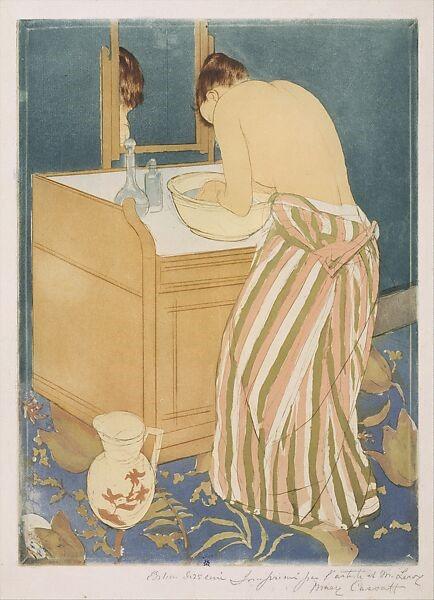

Not only is her work accomplished, with devotion to the craft studied over a lifetime, but she also created during a time when women were supposed to stay at home as housekeepers and mothers. “Women should be someone, not something,” she said.

Born near Pittsburg in 1844, by the time she was 16, Cassatt knew she wanted to be an artist. This single-minded focus enabled her to withstand the many setbacks she endured during a lifetime as a female artist. Cassatt attended classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and at 21, she traveled to Paris where Léon Gérôme took her on as a private student.

Three years later, she exhibited a painting at the Paris Salon, and did so five more times in the 1870s. Returning to Philadelphia at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, she was commissioned to paint copies of two Correggio paintings by the bishop of Pittsburg, warranting her return to Europe.