We hear him sit down and load paper on an old manual typewriter. He begins to type. A close-up of the clanking metal keys spells out, “I am afraid there is only one person in the world who could make a good film about my prints; me.”

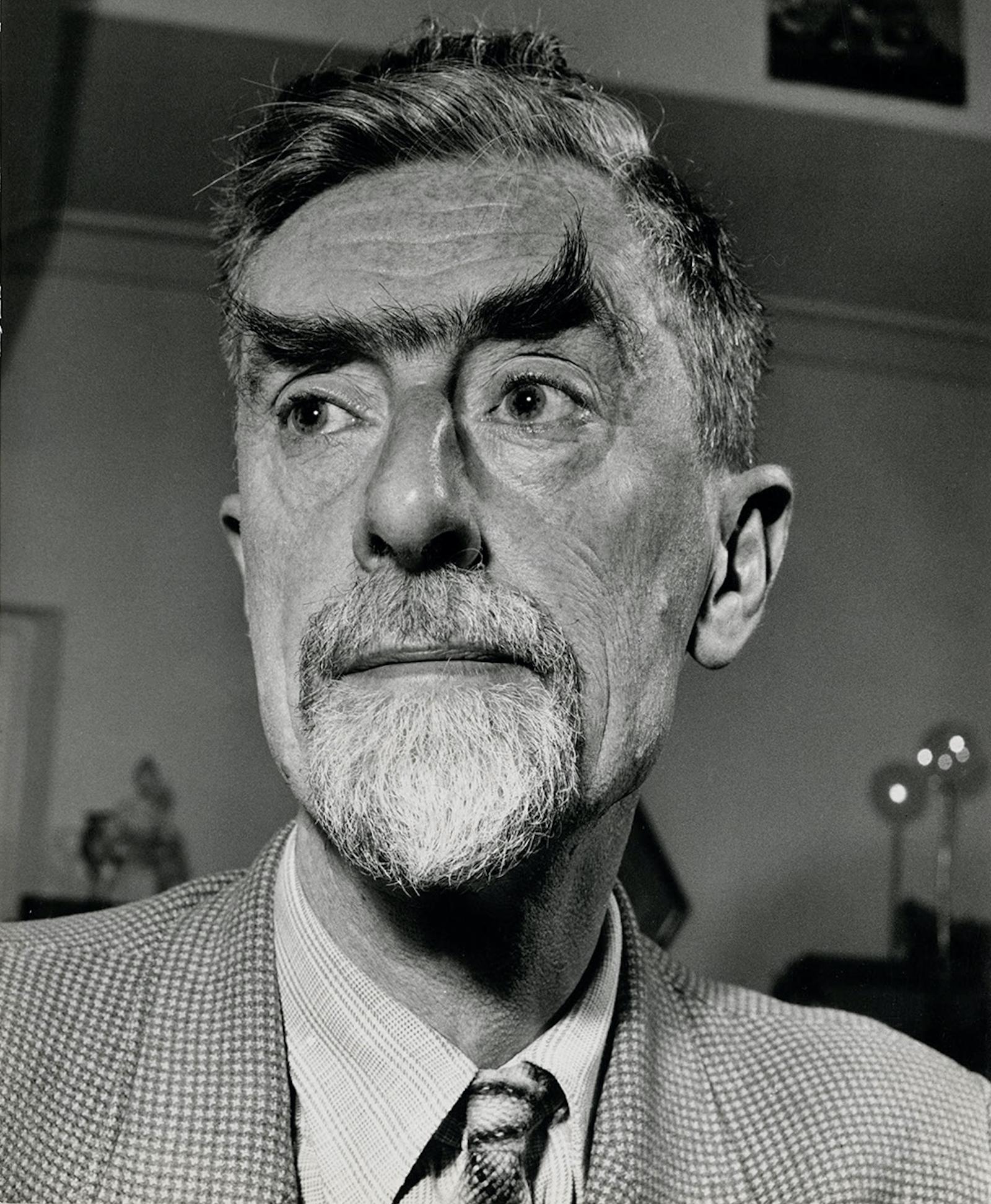

A disembodied Escher self-portrait appears on the screen. His art represents him. The filmmakers have made good on the artist’s declaration to tell his own story. By using Escher’s words lifted from diaries, letters, and other accounts to guide us in this inventively envisioned film, we begin to understand his life and art.

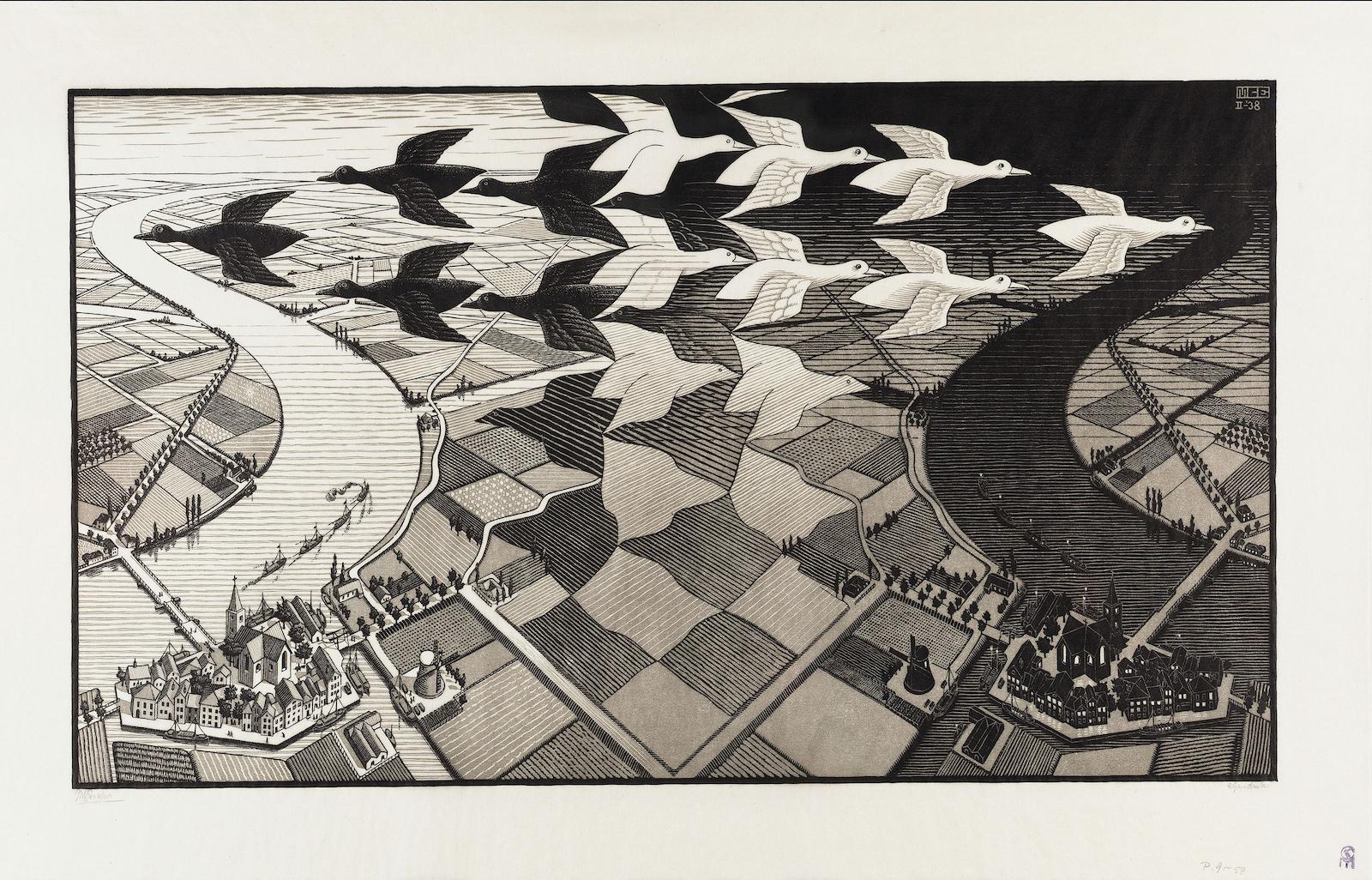

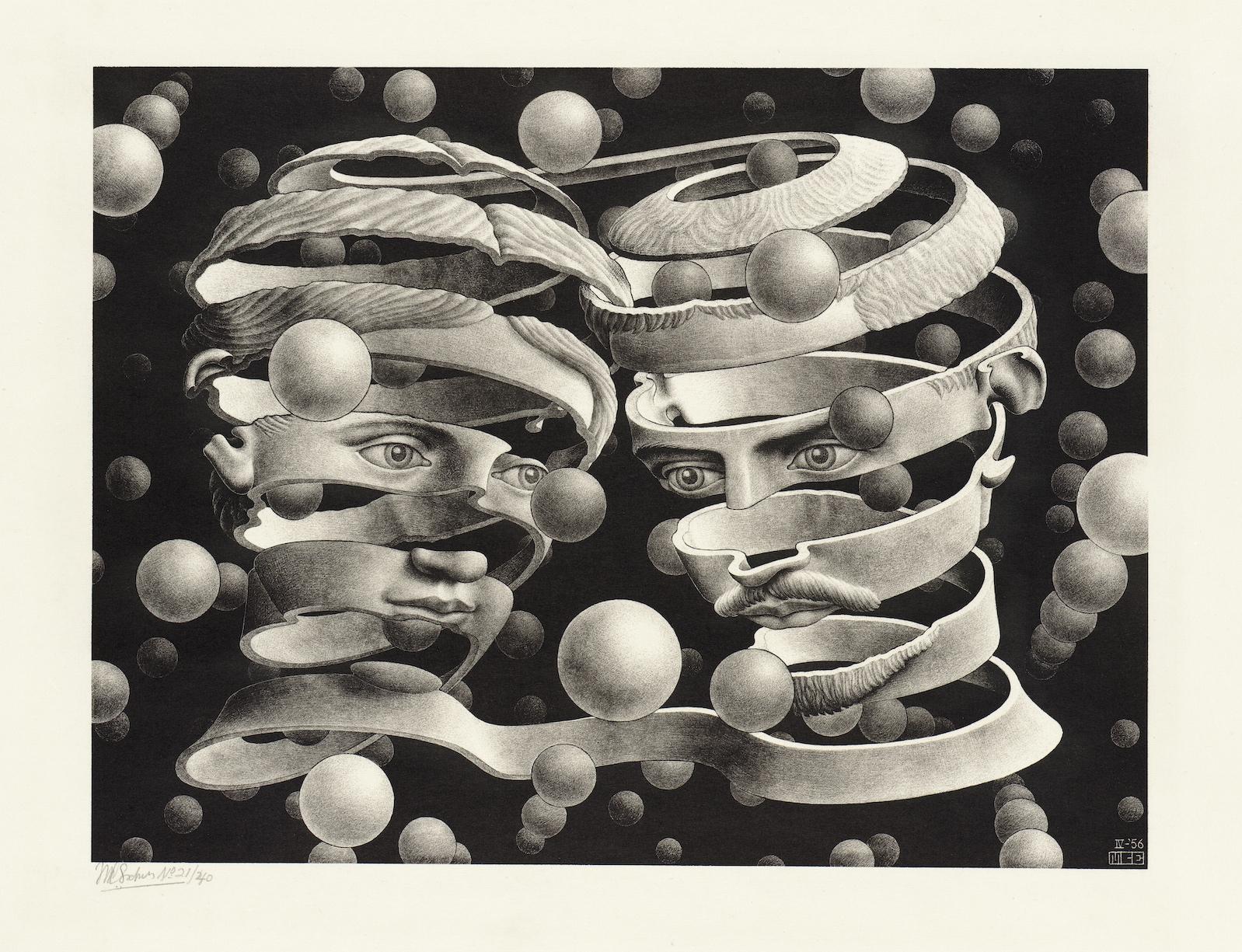

A sensual, bluesy score plays as the camera slowly pans, in close-up, over what appears to be rounded hills of a softly lit moonscape. Underlying the music is a buzzing sound. The camera pulls back, and we see the curves are not hills in a moonscape but a woman’s body and the buzz emanates from a tattoo-artists needle as he etches a classic Escher-inspired design across the woman’s naked back. To tell Escher’s story Lutz has employed the element of surprise and a similar delight in fool-the-eye conundrums utilized by the artist in graphic works that seamlessly morph from one thing into another before our eyes.

Stephen Fry, the British voice-over actor known for his audiobook readings of all seven Harry Potter novels narrates, bringing to life Escher’s wry comments about his education and the development of his artistic methodology. Archival footage, still photos, and clever 3-D animation of Escher’s paradoxical prints moves the story forward. Musician Graham Nash, of the iconic folk-rock group, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, relates his discovery of Escher’s work back in the 1960s declaring, “He changed my life.” Nash contacted Escher to tell him what a great artist he was and was stunned when Escher replied, “I’m not an artist, I’m a mathematician.”