The third segment of the show features portraits of bohemians, dissidents, and activists, including a 1964 painting of civil rights leader James Farmer, who realistically confronts the viewer while sitting in a chair in a highly abstract realm, and a 1970 canvas of gender-bending actress Jackie Curtis, who performed at downtown art venues and in Andy Warhol’s films Flesh and Women in Revolt, posing with occasional collaborator Ritta Redd. Warhol also makes an appearance in Neel’s canvases in the Human Comedy section, which is centered on loss, illness, and injury. Neel painted the pale Pop Art artist in 1970 seated on a sofa with his eyes closed. Shirtless, his torso shows the twisted scars from multiple surgeries that were needed to save his life after he was shot in a 1968 assassination attempt.

Alice Neel, Linda Nochlin and Daisy, 1973. Oil on canvas. Detail on Faces. 55 7/8 × 44 in.

One of the greatest chroniclers of twentieth-century America, Alice Neel was born in a small town near Philadelphia in 1900, but made her mark as a “painter of people,” as she humbly called herself, in New York, where she lived and worked until her death in 1984. The subject of the retrospective exhibition Alice Neel: People Come First at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which includes approximately 100 paintings, drawings, and watercolors made between the 1920s and 1980s, the artist continues to be celebrated for her realistic portraits of regular people.

“Journeying through the exhibition, we can admire her ability to not only capture the psyche of the individual but also reflect the era in which she lived, particularly the unique character of New York,” the Met’s director Max Hollein shared in a videotaped introduction to the show. “Throughout her nearly seventy-year career, Neel remained true to her own vision despite many obstacles, and today her imagery resonates with our own challenging cultural and political circumstances in truly striking ways.”

The comprehensive exhibition, which features a wide variety of Neel’s portraits, still lifes, landscapes, and cityscapes, is divided into eight sections. The first section focuses on Neel’s connection to New York City, where she settled in the early 1930s after graduating from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. Her 1935 portrait Kenneth Fearing, captures the poetry editor of the Marxist Partisan Review at his desk, surrounded by images reflecting his concerns for community. The second section, Home, peers into the artist’s private life and interior spaces through portraits of her lovers and children, as well as still lifes painted in her Spanish Harlem and the Upper West Side apartments, which doubled as her studios.

Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970. Oil and acrylic on linen. 60 × 40 in.

Alice Neel, James Farmer, 1964. Oil on canvas. 43 3/4 × 30 1/4 in.

The next part of the exhibition mixes Neel’s painting-as-drawing style artworks with paintings, drawings, and photographs by her Modernist precursors and contemporaries, such as Mary Cassatt, Jacob Lawrence, and Helen Levitt before moving into Motherhood, one of the most profound parts of the show, with paintings and drawings portraying mothers at all stages of maternity. The 1973 canvas Linda Nochlin and Daisy depicts the feminist scholar and curator doing double duties, like Neel had to carry out, as a mother and professional, while the 1978 painting Margaret Evans Pregnant bridges the Motherhood section of the show with the following part, The Nude, which highlights Neel’s lifelong interest in portraying naked bodies of all sexes and ages.

Alice Neel, Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas. 57 3/4 × 38 1/2 in.

Juxtaposed with her provocative portraits of author Joe Gould and critic and curator John Perreault are naked images of her grandson Andrew, nude portrayals of married couples, and an astonishing self-portrait of the artist at eighty, baring it all. Seated in a blue and white striped armchair with sagging breasts, bulging belly, and paintbrush in hand, Neel looks straight into the eyes of the viewer, as if to frankly say, “This is me. This is who I am.” The abstracted background of the self-portrait provides a path into the final segment of the show, which focuses on the figurative painter’s enduring flirtation with abstraction.

Alice Neel, Self‐Portrait, 1980. Oil on canvas. 53 1/4 × 39 3/4 in.

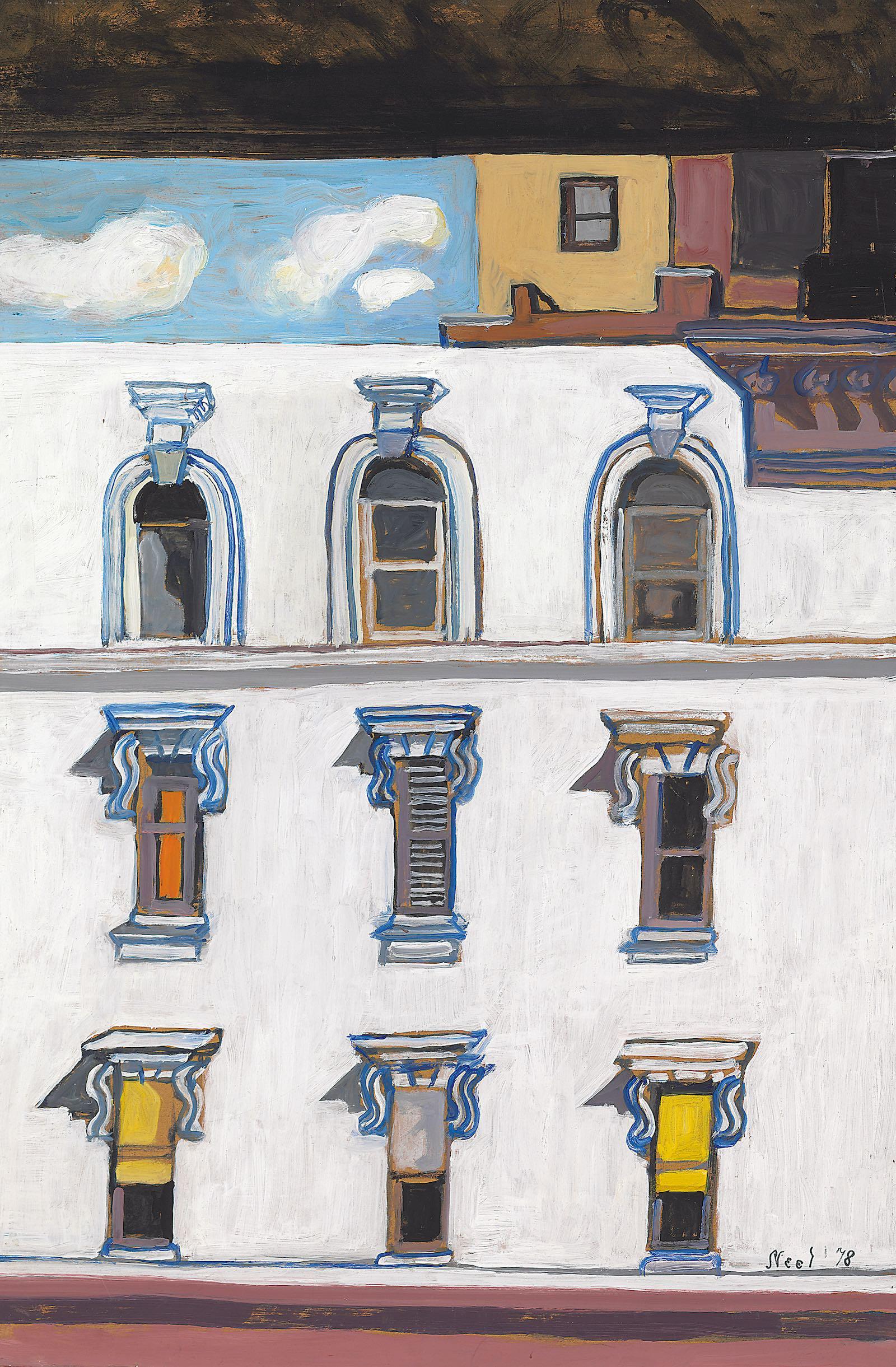

The 1959 painting Night captures the yellow glow of a lit window from a nearby apartment building in darkness. The black and gray shadows on the building’s architecture look like a jagged-edged Clyfford Still painting while the geometric window panes echo the shape of Neel’s canvas. View from the Artist’s Window, from 1978, represents another architectural subject seen from a distance, but this time it's during the light of day, with the distant walls, windows, and sky flattened into two dimensions.

Alice Neel, View from the Artist’s Window, 1978. Oil on Masonite. 29 × 19 in.

“Art, for me, was more than a profession. It was an obsession,” Neel proclaimed in one of the many interviews she gave later in life, and that obsession is center stage at the Met, where the artist’s love of life and embrace of humanity is intensely expressed in every artwork on view.