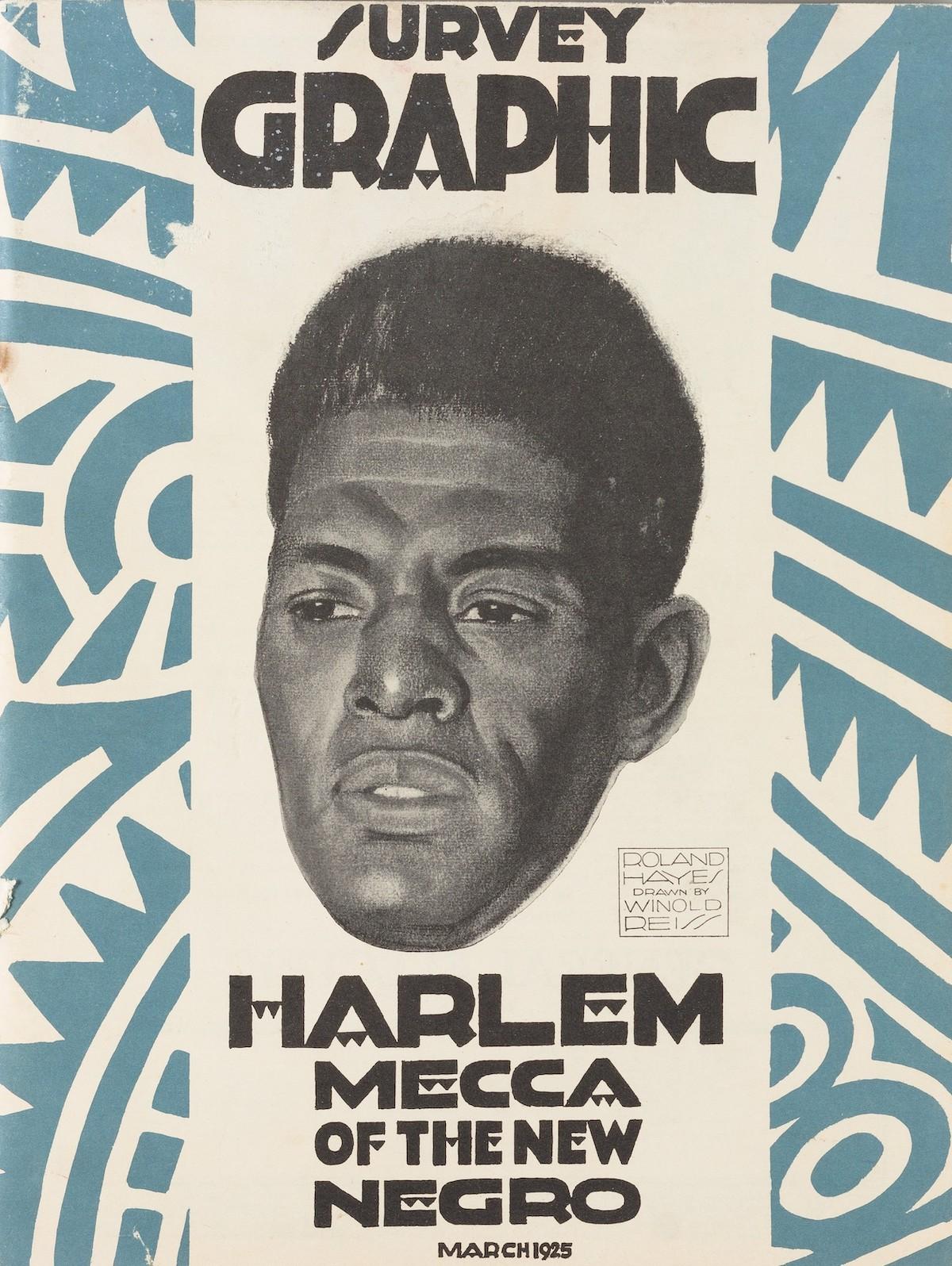

Evidence of the Harlem Renaissance’s universality saturates The Met’s Gallery 999 using nods to Egyptian funerary masks in Ronald Moody’s sculpture, L’Homme (1937), and scatterings of Edvard Munch and Henri Matisse, each situated to fabricate a cycle of artistic influence. The Met prints the debatably unfair demand with which many 20th-century Black American or European artists were burdened—that was to adhere stylistically to either African or Western aesthetics. Writer and ‘philosopher architect’ of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain Locke, whose best-known work was the anthology The New Negro, wrote in favor imitating and therefore revitalizing African and Egyptian aesthetics. Others, however, preferred W.E.B. Du Bois’ interest in academic and contemporary techniques. The Met presents both perspectives in equal measure.

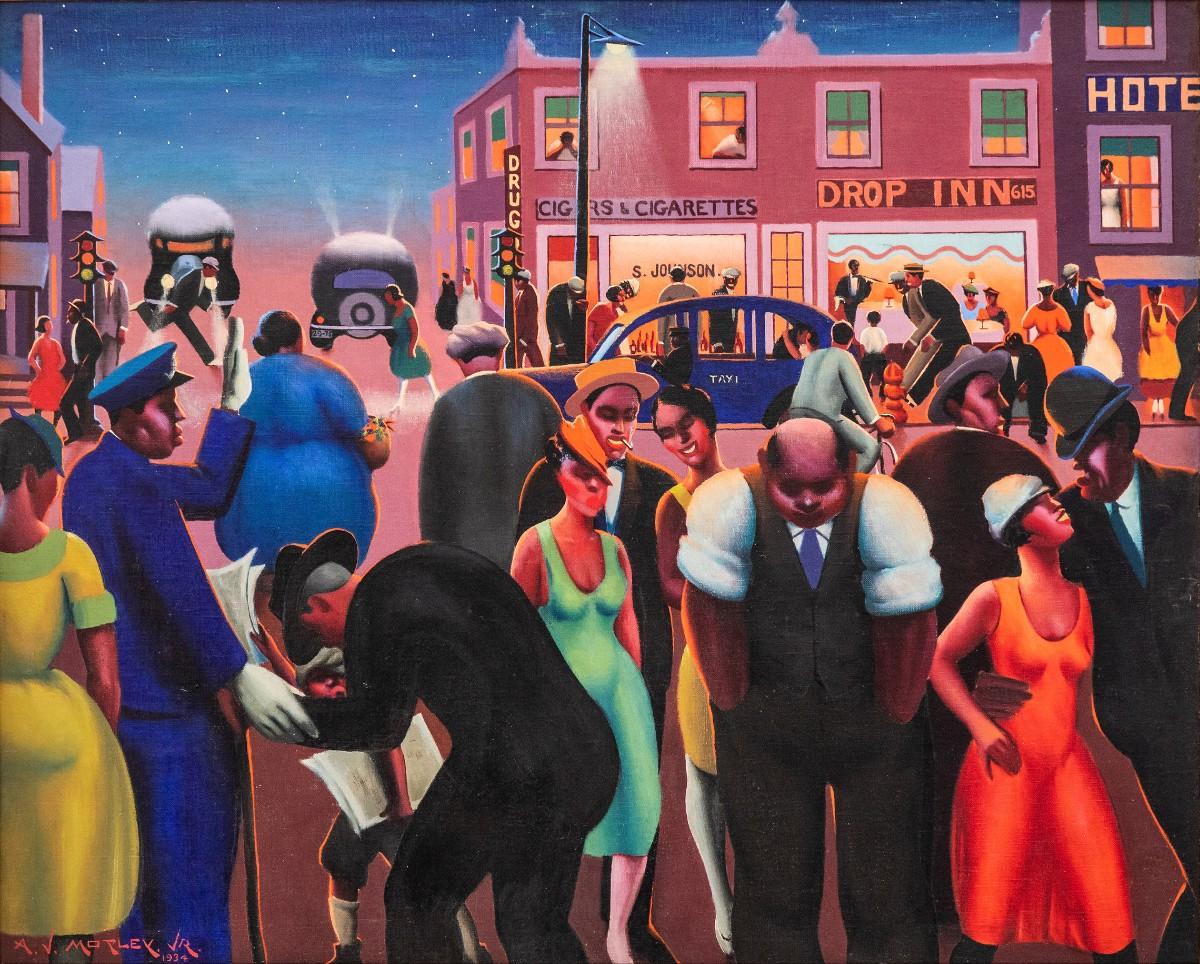

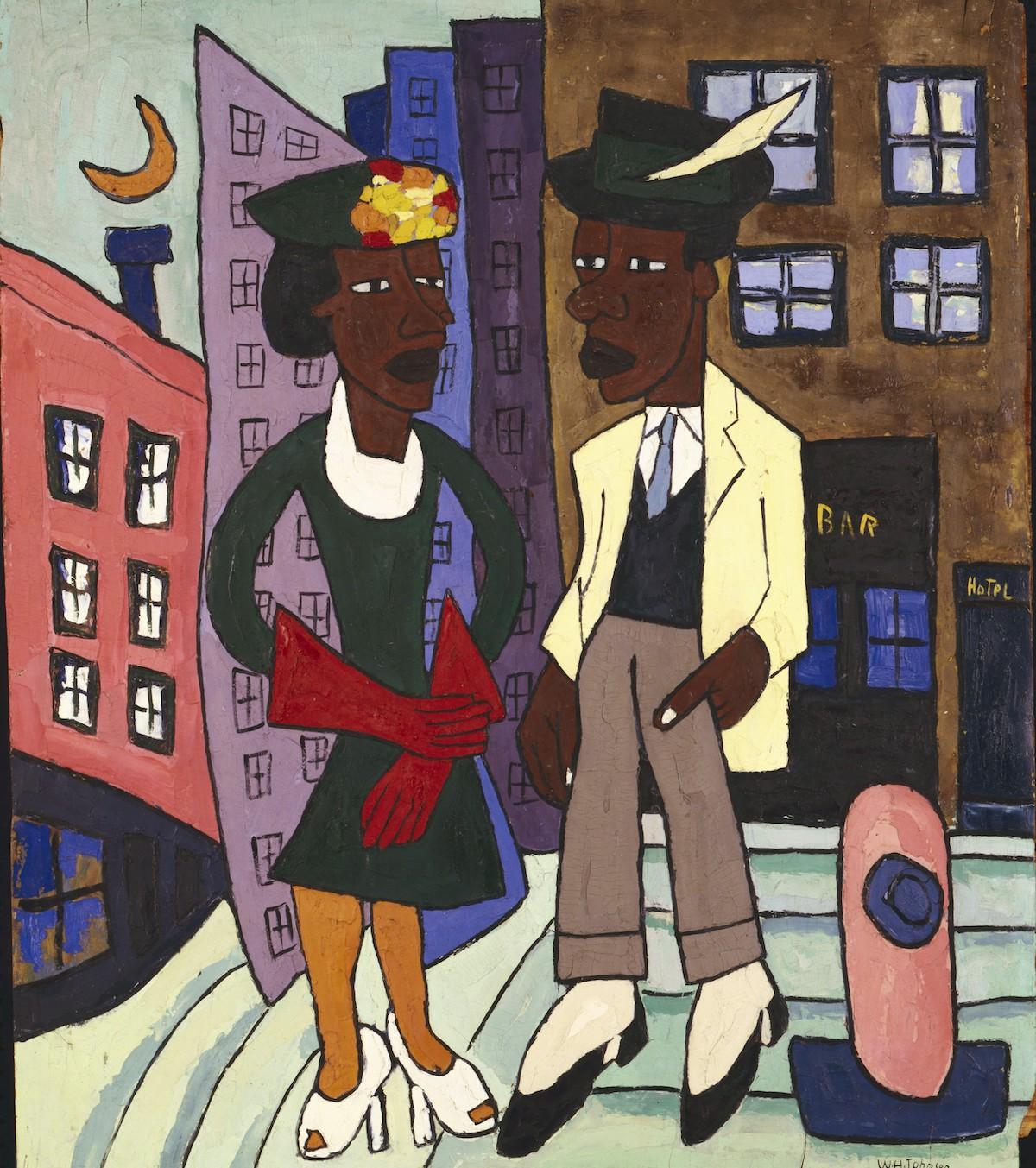

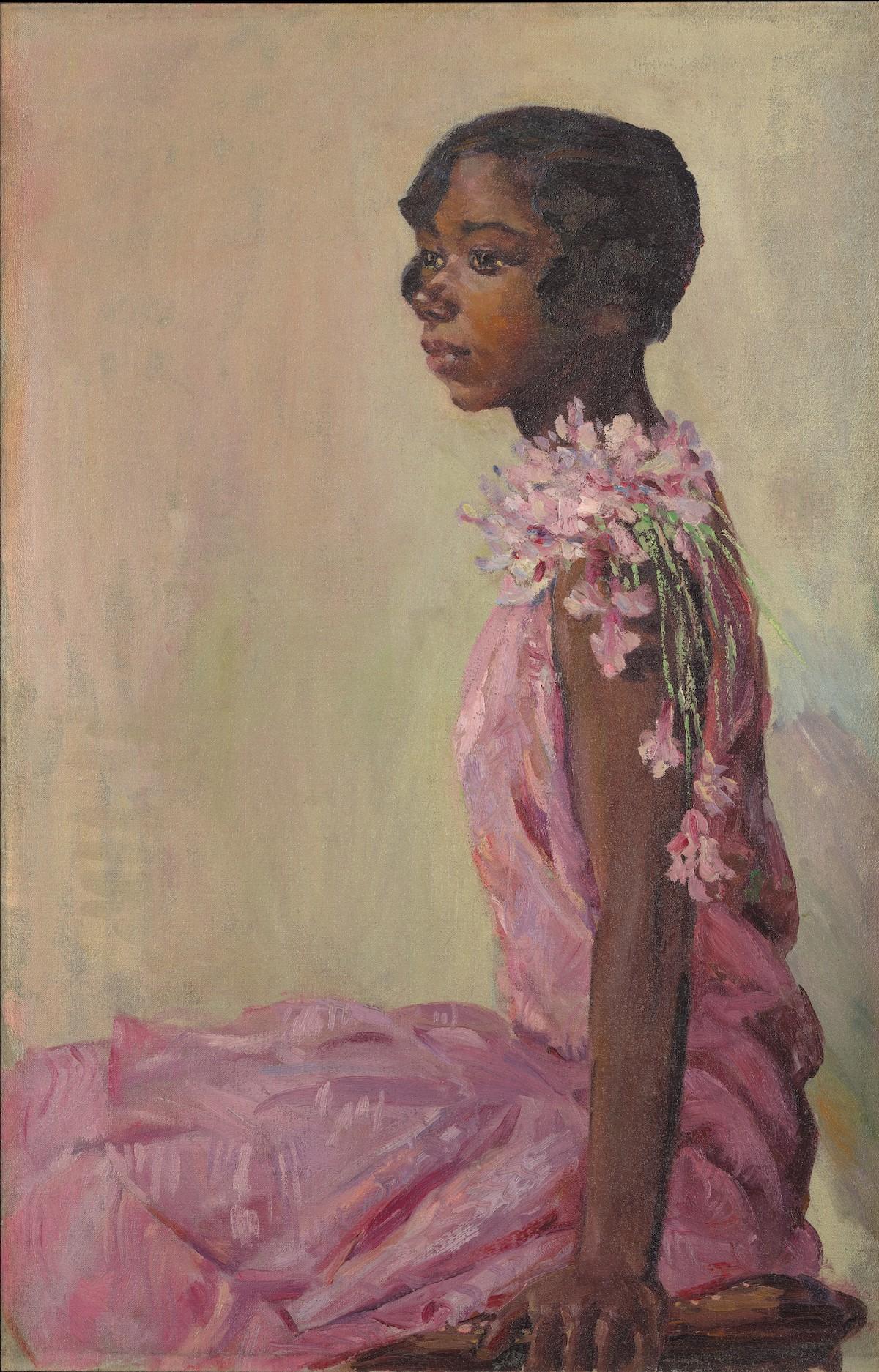

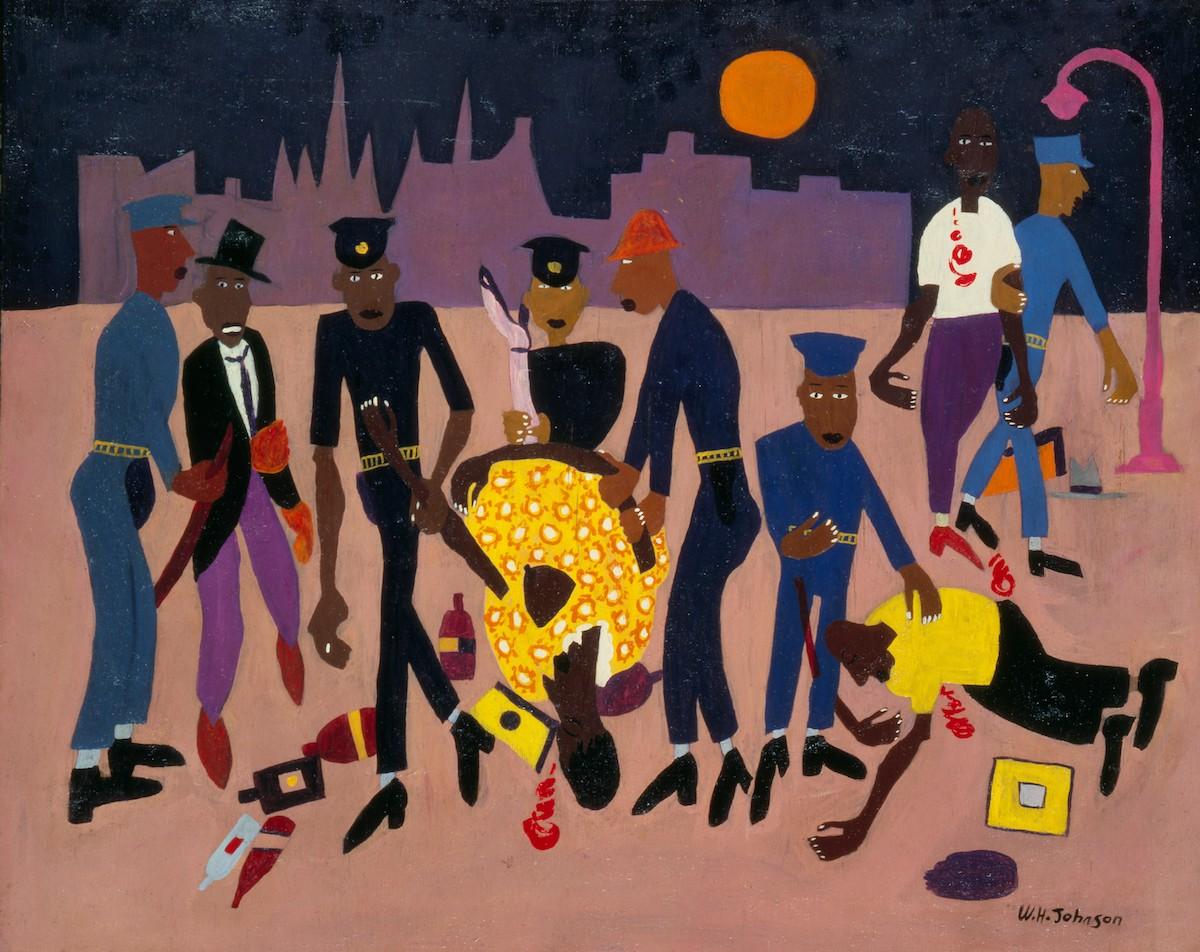

The exhibition is organized into various sections that showcase the facets of Black artistic genius from different angles. The first section, “The Thinkers,” offers portraits of Alain Locke, Zora Neale Hurston, and Langston Hughes with early editions of their great works, The New Negro, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and One-Way Ticket, respectively. Later sections such as “Everyday Life in the New Black Cities” and “Portraiture and the Modern Black Subject” offer works that give snapshots of quotidian society, with dances, meals, and ordinary activities. “Still Life,” “Landscapes,” and “European Modernism and the Transatlantic Diaspora” axiomatically nod toward European influences over American art, deeming the Harlem Renaissance the latest installment in dominant artistic legacies.